Childbirth is a time for expectant mothers to revel in the wonders and joy surrounding the arrival of a new human being; one breathing crisp new air, bawling with resonance in finding their voice and opening their eyes in awe to see the world around them. It’s the last conceivable moment where a mother wants to worry about the cleanliness of the birth facility, the baby’s life and, least of all, her own life. But in many developing countries including Nigeria, this is the reality.

In Nigeria, the statistics on maternal and child health are mind boggling. Some 240,000 babies and 33,000 mothers die each year. Sadly, most of these deaths are preventable. Maternal mortality in Nigeria has decreased from 1,100 per 100,000 births in 1990 to 550 in 2013. Yet, the country, which has only two percent of the world’s population, accounts for some 15 percent of all maternal deaths globally. Lack of access to health care is a major contributor to these high levels of maternal mortality: 42 percent of pregnant Nigerian women receive no antenatal care and 61 percent of childbirths take place with no skilled attendant present.

Evidence in the sector suggests that both supply-side and demand-side factors can impact health service utilization. Supply-side factors include the availability of skilled workers in the health ecosystem, access to essential supplies, and reasonable infrastructure and facilities. Demand-side factors include knowledge, attitudes, and other enablers or barriers to access, which can be addressed through behavior-changing communication campaigns and conditional cash transfer (CCT) programs. A 2012 UNICEF report noted that lack of skilled birth-delivery attendants, inadequate access to decent antenatal care, and maternal postnatal support can all be factors influencing maternal and neonatal death.

So what could actually work and be effective in preventing these deaths? To date, studies that rigorously evaluate programs targeting maternal and child health in Nigeria are limited. And so came to be the Healthy Mothers and Babies Impact Evaluation program. The program brought together a unique tripartite consisting of the Nigerian Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH), the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and the Development Impact Evaluation (DIME) unit of the World Bank’s Development Research Group, to promote the use of scientifically rigorous impact evaluation research to address the high levels of maternal and child mortality in the country. The program was launched in 2013 and, three years later, we are seeing results. The task team leader of the program, Marcus Holmlund, an economist at DIME, filled us in on some outcomes and impacts that will likely inform the next generation of health policies in Nigeria.

Q: Why use impact evaluations?

Marcus: Impact evaluations (IEs) are a great way to find answers to what works and why. Is a program/project/policy achieving its intended results? What are the sizes of the effects? What are the specific mechanisms that drive that impact? The answer to the last question is key to figuring out how to design programs and interventions that work better.

Q: What kind of IEs did you run in Nigeria?

Marcus: We worked with two government-funded programs, the Quality Improvement and Clinical Governance Initiative, which targets the quality of public primary healthcare services, and the Subsidy Reinvestment and Empowerment Program Maternal and Child Health Project (SURE-P MCH). SURE-P MCH was launched in 2012 with funds released from the removal of petroleum subsidies in Nigeria. The program consists of both supply and demand-side interventions to improve availability of and demand for maternal and child health services.

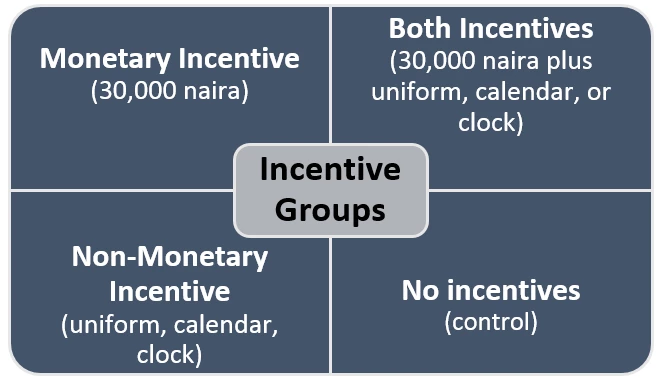

The cornerstone of SURE-P MCH was the provisioning of midwives in areas that previously lacked qualified human health resources. A major challenge observed in previous programs was that health workers often left their posts, for example because the posts were in undesirable locations. So, we implemented an experimental IE using a cluster-randomized controlled trial design to look at the effects of different forms of quarterly attendance-based incentives for midwives: monetary, non-monetary, and combined, compared to a control group receiving no such incentives.

Q: What did your team find?

Marcus: The team leading this study included Pedro Rosa Dias from Imperial College Business School, Marcos Vera-Hernandez from University College London (UCL), and Pamela Jervis Ortiz, also from UCL. We found midwives that received quarterly monetary incentives (either alone, or together with non-monetary incentives) were 6.3 percentage points less likely to leave. This is equivalent to a reduction in midwife attrition of 20 percent from the control group drop-out rate of 31 percent. Eligibility to receive non-monetary incentives (either alone, or together with monetary incentives), however, did not have any effect on reducing attrition. These findings show that, on average, economically meaningful incentives can reduce midwife attrition.

We also considered some mechanisms through which incentives may, or may not, work, and this led to several interesting observations. For example, we saw that incentives can backfire and be detrimental to highly intrinsically motivated individuals. So, the effectiveness of incentives may depend on the design of the incentives and also on the characteristics of the persons receiving the incentives. We also found evidence of implicit information being conveyed through incentive schemes, which suggests we have to be mindful of how incentive schemes are communicated.

Q: Where does your team go from here?

Marcus: We’re doing all we can to get the messages out. We will hold a policymaker summit (Evidence and Prospects for a Healthy Nigeria) in Abuja, on March 30 and 31, 2016, where we will present evidence and conclusions from five recently-completed health sector impact evaluations. The topics will include maternal and child health, primary healthcare service delivery, midwife retention, prevention of sexually transmitted infections, and prevention and treatment of malaria. We hope this will provide a constructive forum to stimulate discussion on the implications of this evidence for health policies and to strengthen partnerships for future IE knowledge creation in the Nigerian health sector.

We are very grateful to our partners in the Nigerian government for making these IEs possible, to the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation for strategic guidance and funding, and to the Strategic Impact Evaluation Fund and Japan Social Development Fund, both of which also supported aspects of this work.

---------------------------------------

Interested in understanding the life of a Nigerian midwife? Watch a day in the life of Christy, one of the midwives in the SURE-P MCH program, as she delivers babies, immunizes children, and provides general care to mothers and babies.

Join the Conversation