Aerial view of the city of Bogota, Colombia © PAYM photography/Shutterstock

Aerial view of the city of Bogota, Colombia © PAYM photography/Shutterstock

Spatial equilibrium is a central principle in economic geography and urban economics. It implies that in a country where labor mobility is high, spatial differences in real wages and welfare will be negligible. In equilibrium, all the advantages of a place, such as a good climate, natural beauty, cultural, educational, and economic opportunities, are supposed to be offset by countervailing disadvantages, such as long commutes, pollution, crime and the high cost of living, to name a few. Spatial differences in happiness have been relatively small in developed countries, as shown by Pittau, Zelli, and Gelman (2010) in the case of Europe.

However, this hypothesis has been rejected for some large developing economies. Chauvin et al. (2016) question the applicability of the frictionless spatial equilibrium hypothesis in India and China, where people have a strong attachment to their place of birth and barriers to mobility like China’s Hukou system may result in persistent spatial differences in welfare. Rural-urban happiness differentials have also been much larger in the developing countries, as discussed in Burger, Morrison, Hendriks, and Hoogerbrugge (2020).

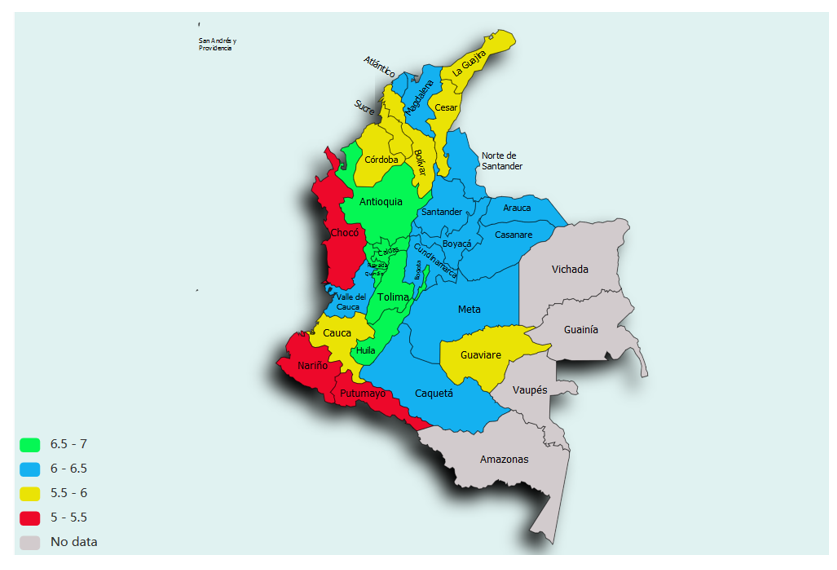

In a recent paper, we explore spatial differences in welfare in Colombia. We use subjective well-being data from the Gallup World Poll as a proxy for welfare and interpret large differences in subjective well-being as evidence against spatial equilibrium, following Glaeser, Gottlieb and Ziv (2016). A priori we have reasons to expect that the spatial equilibrium hypothesis would apply to Colombia. It is an upper-middle income, OECD country with average levels of happiness comparable to those in many developed countries and high levels of rural to urban migration. Yet, data on happiness, shown in Figure 1, indicate large differences in subjective well-being across space.

Figure 1. Happiness levels in Colombia across regions

Source: Average Cantril Ladder Scores from Gallup World Poll (2010-2018) proxy happiness levels and are based on the question: Please imagine a ladder, with steps numbered from 0 at the bottom to 10 at the top. The top of the ladder represents the best possible life for you and the bottom of the ladder represents the worst possible life for you. On which step of the ladder would you say you personally feel you stand at this time?

In the core regions of Colombia, where Bogotá, Caldas, and Quindío are located, average levels of happiness are well above those in European nations like France and Spain. However, in the peripheral regions of Chocó, Nariño and Putumayo, average happiness levels are below those in poorer Latin American countries like Bolivia and Paraguay. There is also a large urban-rural divide in Colombia. The percentage of thriving people – those assessing their subjective well-being at 7 or higher – in predominantly rural areas (39%) is considerably lower than the percentage of thriving people in urban areas (57%).

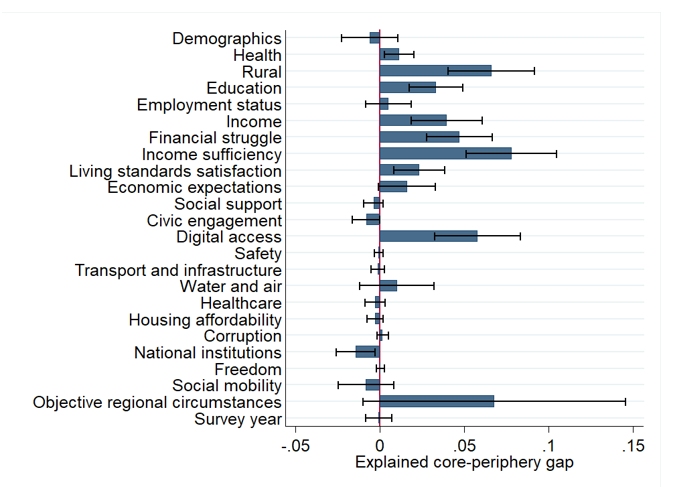

What explains these large spatial differences in happiness? As shown in Figure 2, some of the core-periphery differences can be explained by the higher education and income levels of residents in the core relative to the periphery, reflecting the skill sorting in the large agglomerations of the core regions. It also seems that the advantages of core regions in terms of economic opportunities are not fully compensated by countervailing disadvantages. As expected, fewer residents are satisfied with housing affordability in the core than in the periphery, but this does not affect in a significant way experienced welfare in the core relative to the periphery. There are hardly any core-periphery differences in satisfaction with public transportation and road infrastructure and the percentage of residents satisfied with water quality is higher in the core than the peripheral regions, but the opposite is the case when it comes to air quality. All in all, the periphery, which tends to have a larger rural population, has a higher percentage of residents experiencing financial insecurity, health problems and dissatisfaction with digital access and their living standards. Similar conclusions can be obtained if one looks at the factors associated with rural-urban differences in happiness.

Figure 2. Factors explaining the core-periphery difference in happiness

Note: Results obtained using weighted least squares on the split sample between core and peripheral regions and Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition analysis which divides the differential into an explained part (73%), associated with core-periphery differences in endowments and perceived conditions, and an unexplained part (27%), associated with core-periphery differences in preferences and omitted factors. For graphical representation some variables have been grouped. Demographics: age, gender, marital status, children, religion, and migrant status; Health: health problems and pain; Economic expectations: personal economic optimism and optimism about economic climate; Transport and infrastructure: satisfaction with public transport and satisfaction with roads and highways; Social mobility: Social mobility is possible and satisfied with poverty policy; Objective regional circumstances: Regional GDP per capita and share of Venezuelan migrants.

The large differences in experienced welfare despite high rural to urban migration suggest that the spatial equilibrium hypothesis most likely does not apply in the case of Colombia. This has important implications not only for research, but also for policy. Colombia is in the process of regaining stability after a long period of civil war during which rebels operated mostly in peripheral and rural areas. Efforts to improve conditions in these parts of the country, including water quality, digital access, and economic opportunities, will increase well-being in these areas, lower inequality in happiness, and nurture the fragile peace struck between rebels and the state. Such efforts will also reduce ethnic inequality in well-being and improve inclusion of Afro-descendants, concentrated in the coastal regions, and Amerindians, located primarily in the Eastern periphery of the country.

Join the Conversation