Primary school teachers in Islamabad, Pakistan. Photo: STARS/Kristian Buus

Primary school teachers in Islamabad, Pakistan. Photo: STARS/Kristian Buus

Recognition or mutual acceptance of people’s equal rights is considered a fundamental prerequisite for economic and political empowerment of vulnerable groups. But in much of the world, women still have fewer labor market and educational opportunities, lower physical mobility, less autonomy to run for political office or to make their own decisions. Many of these limitations can be attributed to social norms, which are inherently ingrained and slow to change.

The women’s rights issue is a prominent example, where considerable differences exist across and even within societies. Often, those who challenge traditional norms –norm disrupters – meet fierce resistance and ultimately pay a price through denunciations, social stigma, and even outright violence.

But, then what stymies rights revolutions? How can rights revolutions be fostered?

In our new paper, we show that new nonconformist ideas in society can be fostered, but at a cost. Some of these costs, nevertheless, dissipate once the new norms diffuse in society. In particular, we suggest two broad explanations: internal and external social sanctions. We measure internal sanctions via increase in stress levels measured by blood concentrations of cortisol and external sanctions by the incidences of domestic violence. Understanding which of these is more amenable to change is crucial for understanding the adherence of traditional norms and to create policy to shift potentially harmful attitudes.

The Experiment

Our experiment consisted of implementing a randomized control trial with female Pakistani teachers in collaboration with the Progressive Education Network (PEN). Our sample consisted of 607 teachers and their 13,932 pupils across schools in the state of Punjab. We randomly assigned teachers to a Visual Narrative—a live screening of the movie “Bol”, roughly 3 hours long, and set in contemporary Pakistan dealing with the issue of women’s rights. We also used a joint treatment where we supplemented the visual narrative with a semester-long gender studies curriculum taught in class for four months, where teachers and students were prompted to self-reflect on and to envision equal rights for men and women.

Teachers’ gender attitudes were measured in three ways: using indices from surveys eliciting views on women’s rights; the gender Implicit Associations Tests (IAT)— which measure implicit gender bias using word associations— and by teachers’ decision to petition the Pakistani Parliament for more equal rights. To assess teachers’ stress levels, we measured self-reported perceptions of stress, as well as blood concentrations of cortisol—the hormone secreted in response to stress. In the context of gender attitudes, we proxied for external social sanctions by looking at the incidences of domestic violence experienced by the teachers.

Impact on gender attitudes of teachers and students

One year after the experiment, we found that using a visual narrative to train teachers shifted the teachers’ attitudes towards more equitable gender rights . The effect sizes are substantial. Teachers’ attitudes measured in gender IATs shifted by 0.2 standard deviation. The teachers also became about 0.35 standard deviations more likely to petition the Pakistani parliament to repeal discriminatory laws. Reinforcing the visual narrative with the gender-rights curriculum multiplied these effects— even when the visual narrative experiment focused specifically on the teachers, it also had impact on their pupils who were found to have more progressive gender attitudes (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Distribution of Teachers’ Gender Rights Index

The Cost of Rights Revolution: Impact on stress and domestic violence

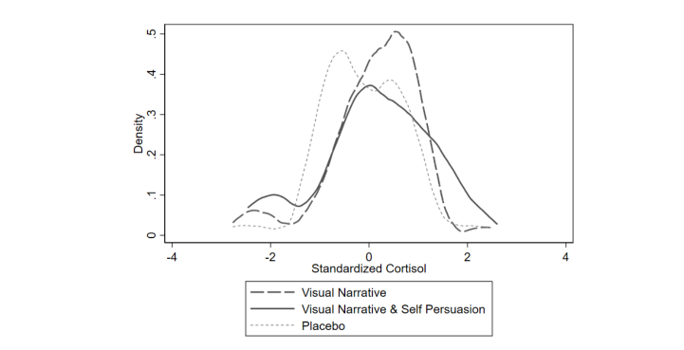

Our findings showed that having more progressive gender attitudes also accompanies heightened stress . The increased recognition of gender rights by teachers elevated their blood cortisol concentrations by 0.3 standard deviations and domestic violence by 0.35 standard deviations. These increases are persistent, such that even a year after the intervention, cortisol concentrations remained elevated by 0.35 standard deviations for the treated group (Figure 2). These costs, however, dimmish as more teachers hold these progressive gender attitudes.

We also noted that teachers that were shown the visual narrative had about a 0.25 standard deviations higher likelihood to report they had experienced domestic violence compared to the control group. We see no statistically discernible change in their attitudes towards domestic violence. Our results hold even after accounting for potential misreporting of domestic violence or spillover effects.

Figure 2: Distribution of Teachers’ Blood Cortisol Levels

Note: The distributions for blood cortisol readings are reported with the variable standardized to mean zero and standard deviation one.

Evidence for Moral Bandwagoning

Our empirical design allowed us to investigate how the costs associated with rights revolutions can be mitigated. We used random variation in the group of treated teachers within a school to explore whether moral bandwagoning—the phenomenon that exists when people do something primarily because others are doing it, regardless of their own beliefs, which they may ignore or override— reduces the cost of norm subversion, meaning that if enough teachers change their pre-existing beliefs, the psychological costs of departing from traditional gender norms goes down. We found that when about 45 percent of the teachers were treated with our norm changing treatments, the adverse impact on stress disappeared. This suggests that greater community adoption can lower the potential costs associated with holding on to internalized norms. But, moral bandwagoning does not seem to manifest itself in the case of social sanctions such as domestic violence, indicating that the backlash effect or external sanctions can impede one’s ability to change norms or beliefs that could have otherwise been possible in the absence of these external sanctions.

Conclusion

Our paper provides an explanation on why rights revolutions are not universal and disentangles two channels for punishing norm subverters: internal sanction of increased stress and external sanctions of domestic violence . While heightened internal stress dissipates as the norm becomes more widely adopted, the costs from external sanctions, such as domestic violence, persist. This finding highlights that social campaigns for equal rights, targeting a single group to change from potentially harmful norms have limitations if they don’t also address backlash from those groups that have not yet adopted the new norms .

Join the Conversation