Women create terraces in Rwanda. Photo: A'Melody Lee / World Bank

Women create terraces in Rwanda. Photo: A'Melody Lee / World Bank

On January 24, 2020, a quiet revolution happened in South Africa. In a landmark ruling in the Durban High Court, 72-year old Agnes Sithole scored a legal victory that not only provided her a share of her husband’s estate but may also help to protect an estimated 400,000 black elderly women in South Africa. Facing impoverishment when her marriage ended, Ms. Sithole challenged a discriminatory law dating back to the apartheid era under which black women married before 1988 were denied ownership of family property, as all matrimonial assets belonged to the husband. The new ruling stipulates that all such marriages are to be declared in community of property, a marital property regime that treats the property of either spouse as joint property regardless of who paid for it.

This case from South Africa illustrates that legal systems are often biased against women and impede their access to property. However, until recently, there has been no systematic data on gender gaps in property ownership in developing countries that would allow to document these gaps. This has started to change over the last decade. In 2009, the Gender Asset Gap Project highlighted the feasibility of collecting individual-level data on property and other assets. And in 2010, the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) first started collecting data on the ownership of land and housing for adult women and men, which by now covers approximately 40 countries. Land, which includes agricultural and non-agricultural land, and housing are both important assets for the poor in developing countries and the primary means to accumulate wealth in rural communities, with housing property growing in importance due to urbanization. In a recent paper, we use the DHS data to explore gender gaps in the incidence of land and housing property among married couples, and the factors associated with these gaps. This is, to the best of our knowledge, the first global empirical assessment of gender gaps in property ownership. Here are three main takeaways from the analysis.

1. While there is large variation across countries, men are more likely to own property than women almost everywhere

Figure 1 shows the percentage point difference between men and women in the incidence of land and housing ownership at the country level (a positive value indicating that more men than women own property). We combine sole and joint ownership, i.e. we do not differentiate if a women or men owns property alone or jointly with someone else, typically their spouse. In all but one country (the Comoros), women are less likely than men to claim ownership over land and housing. For most countries, gender gaps in the ownership of land are greater than in the ownership of housing. And because women are more likely than men to report joint ownership, gender gaps in property ownership are even stronger if we only consider sole ownership. Geographically, the largest gender gaps in property ownership are found in West and Central Africa, South Asia, Europe and Central Asia and the Middle East and North Africa.

Figure 1: Gender gaps in land and housing ownership among married couples favor men

Note: See here for a list of country codes.

2. Within countries, gender gaps are most pronounced for groups that are already disadvantaged.

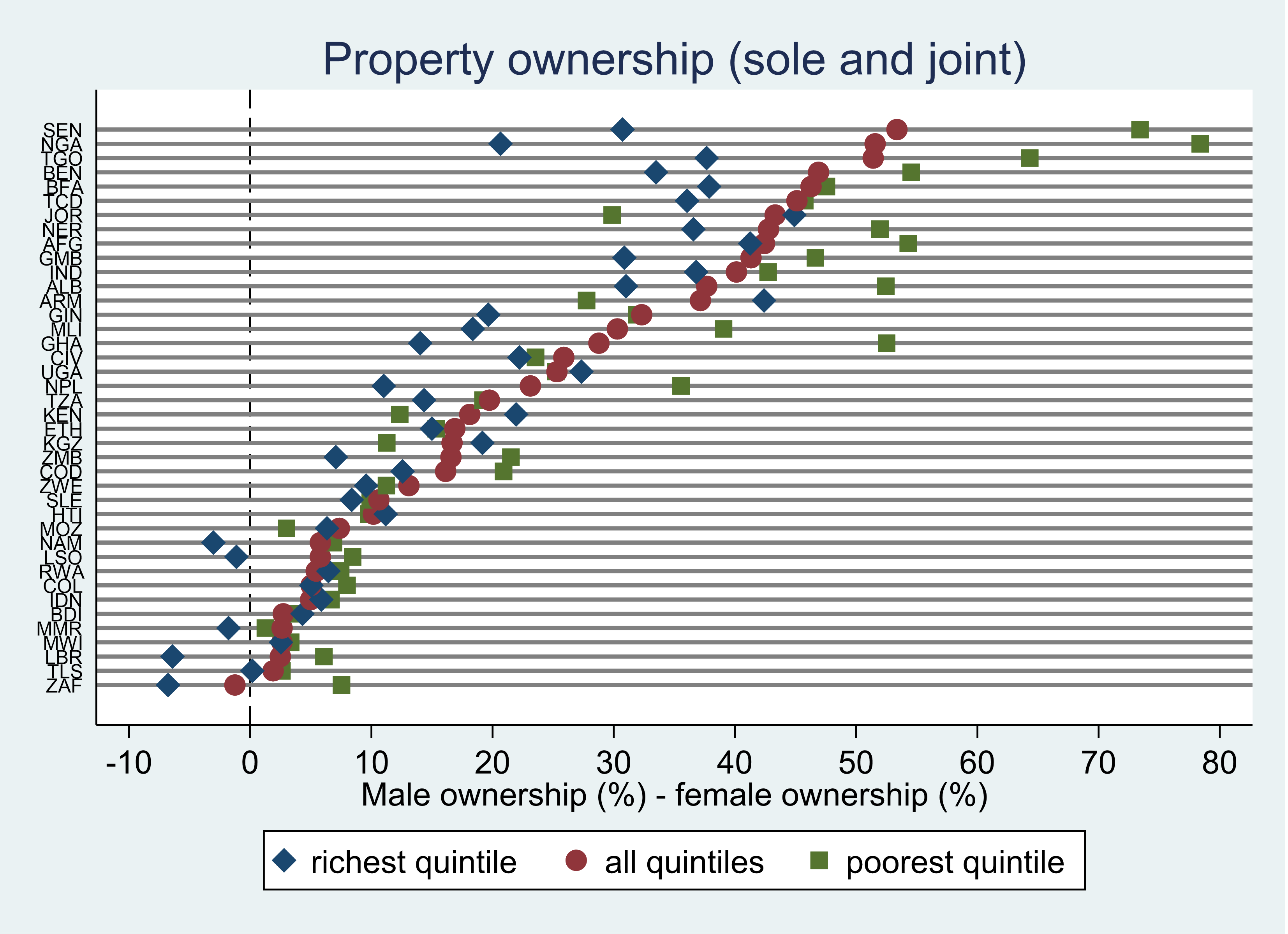

Figure 2 plots gender gaps in property ownership by country and quintile, using the DHS index of household wealth to rank households from the poorest to the richest quintile. To simplify matters, land and housing ownership is combined into a single indicator of property ownership. Gender gaps in sole and joint ownership of property are typically larger for the poorest than for the richest quintile, a pattern that holds even more strongly for sole ownership. A similar picture emerges when we compare rural and urban areas, with gender gaps in property ownership being larger in rural than in urban areas.

Figure 2: Gender gaps in property ownership among married couples are larger for the poorest quintile

3. Countries with more gender egalitarian legal regimes have higher levels of property ownership by women, especially housing.

In a final step, we investigate the question if discriminatory laws and regulations could be one factor to explain the large gender gaps in property ownership documented above. This analysis draws on the World Bank’s Women, Business and the Law (WBL) data, which has been widely used to document gender biases in counties’ legal systems. The new feature of our paper is that we link the WBL data to the DHS data on men’s and women’s property ownership to explore if gender gaps are associated with discriminatory laws and regulations. We focus on four areas of legislation that we expect may have a negative association with women’s ability to own any land or housing:

- Legal recognition of nonmonetary contributions to marital property: Because women are more likely than men to perform unpaid activities that benefit the household (e.g. caring for children) they have fewer opportunities to acquire property during the marriage. Legal recognition of nonmonetary contributions, which is implicit in community property regimes, is hence important for women as it grants them access to a share of marital property upon the dissolution of marriage.

- Equal inheritance rights: This captures if the law provides for equal inheritance rights between male and female surviving spouses, and between male and female children.

- Equal ownership rights to immovable property: This indicator picks up discrimination by gender not only in the legal ability to own property, but also in the legal treatment of spousal property.

- Equal remuneration for work of equal value: Though not directly related to property rights, this indicator captures gender discrimination in pay, given the centrality of earnings for property acquisitions.

Our results show that countries with more gender-equal legal regimes for women are associated with higher property ownership by women. The relationship between the legislation and women’s property ownership holds across rural and urban areas and is stronger for housing than for land. There is further indication that equal rights to own property and laws providing for the valuation of non-monetary contributions may matter more for married women’s property ownership than inheritance rights and laws mandating equal remuneration for equal work.

Overall, these results suggest that reforms to establish a more gender-equitable legislative framework, such as the ones fought for by Ms. Sithole in South Africa, may be an important mechanism to increase women’s property ownership.

Join the Conversation