The youth bulge is a common phenomenon in many developing countries, and in particular, in the least developed countries. It is often due to a stage of development where a country achieves success in reducing infant mortality but mothers still have a high fertility rate. The result is that a large share of the population is comprised of children and young adults, and today’s children are tomorrow’s young adults.

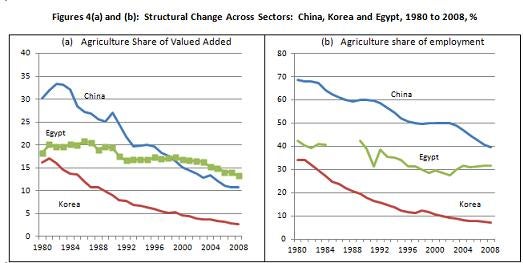

Figures 1 (a)-(b) provide some illustrative examples. Dividing the world into more and less developed groupings (by UN definitions) reveals a large difference in the age distribution of the population. The share of the population in the 15 to 29 age bracket is about 7 percentage points higher for the less developed world than the more developed regions. In Africa (both Sub-Saharan and North Africa), we see that about 40 percent of the population is under 15, and nearly 70 percent is under 30 (Figure 1(a)). In a decade, Africa’s share of the population between 15 and 29 years of age may reach 28 percent of its population. In some countries in “fragile situations” (by World Bank definitions), almost three-quarters of the population is under 30 (examples in Figure 1(b)), and a large share of 15-29 year olds will persist for decades to come (Figures 1(c) and (d)).

Source: Author’s calculations based on data from United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2011). World Population Prospects: The 2010 Revision. Medium fertility scenario is used for the 2050 projections.

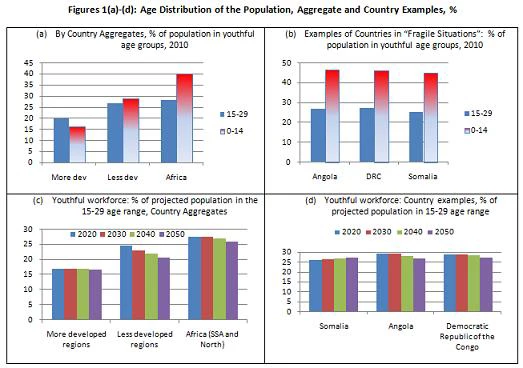

In a country with a youth bulge, as the young adults enter the working age, the country’s dependency ratio-- that is, the ratio of the non-working age population to the working age population—will decline. If the increase in the number of working age individuals can be fully employed in productive activities, other things being equal, the level of average income per capita should increase as a result. The youth bulge will become a demographic dividend. However, if a large cohort of young people cannot find employment and earn satisfactory income, the youth bulge will become a demographic bomb, because a large mass of frustrated youth is likely to become a potential source of social and political instability1.Therefore, one basic measure of a country’s success in turning the youth bulge into a demographic dividend is the youth (un)employment rate. Unfortunately, the recent record has not been favorable. While unemployment rates are naturally higher for young people, given their limited work experience, the double digit unemployment rates presented in Figure 2 are worrisome. Typically, the prevailing youth unemployment rates are about twice the rate of the general workforce. The situation in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) and in the countries of Europe and Central Asia is particularly troubling: youth unemployment is on the order of 20 percent or even higher. In addition, informality is more prevalent among youth in MENA, so even for those who are employed, there may be problems with job quality2.

Source: World Development Indicators and ILO Global Employment Trends for Youth. Two lines for MENA in recent years are for the separate sub-regions of the Middle East and North Africa by ILO definitions.

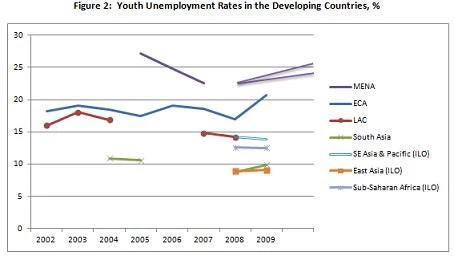

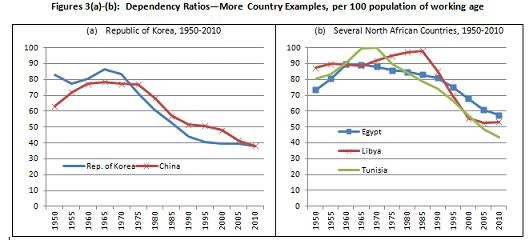

East Asian economies have been able to turn to the youth bulge into a demographic dividend. Take the Republic of Korea as an example. Over the past forty years, the dependency ratio declined substantially in Korea (Figure 4(a)). In addition to dramatic GDP growth and rapid increases in average wages, youth unemployment has been below 12 percent and often in the single digits in recent years (ILO data cited above). The same is true for China. Its dependency ratio followed a similar pattern to Korea’s (Figure 1(a)). Since initiating economic reforms since the late 1970, China has been able to generate millions of new jobs while also relocating young workers from lower productivity agricultural activities to higher productivity manufacturing—all without experiencing high unemployment among the youthful labor force. In recent decades, countries in North Africa have also experienced dramatic declines in the dependency ratio (Figure 3(b)); however, as we saw above (Figure 2), youth unemployment has been a severe problem.

Source: United Nations, World Population Prospects: the 2010 Revision.

The Traditional Policy Response: Prepare the Youthful Supply of Labor

The conventional approach for dealing with youth bulge is to make young people job ready. The idea is that young people’s skills – or more broadly, human capital—needs to be increased to enhance their productivity in the labor market. The 2007 World Development Report, Development and the Next Generation, lays out the policy agenda by focusing on five key life transitions: learning, work, health, family, and citizenship. Three “lenses” are used to focus the policy discussion: opportunities, capabilities and second chances. Basic skills and access to secondary and tertiary education, for example, are needed to create opportunities, while capabilities to make the right decisions for seizing opportunities can be enhanced through better information, access to credit and other factors. On the other hand, when outcomes are negative—for example, poor decisions lead to low levels of education or exposure to communicable diseases—young adults may need access to services that can help them re-start their economic and personal lives. The 2007 WDR emphasized both the skills upgrading and the institutional setting for improving economic outcomes for young people.

The above discussion provides a useful framework for mitigating youth unemployment issue from the supply side; however, demand for labor services is essential for absorbing new entrants to the workforce. Such a shift in demand can be achieved only by a dynamic change in economic structure. Countries that have been successful in this regard move from a high share of employment in agriculture towards an increasing share of employment in manufacturing first and then gradually to the service sector in the post industrialization stage. Generally, this structural change is accompanied by rural-urban migration, and it usually starts in labor intensive manufacturing. On an aggregate level, one can look at the sectoral shift out of agriculture and into industry and services – both in terms of value-added and employment. For example, Egypt in 1980 had a GDP per capita (in constant 2005 PPP dollars) of $2,400, while China was only at $524 and Korea was already ten times higher at $5500 (WDI data). Egypt had only a slightly higer share of agriculture and employment in GDP, compared to Korea; however, this structure largely stagnated in the case of Egypt in the ensuing decades (Figures 4(a) and (b)). Meanwhile, China now with a GDP per capita of $6800 (2005 constant PPP) has a lower share of agriculture in total value added and the employment share has declined continuously. On a more micro level, countries like Korea have then moved up the industrial ladder to more sophisticated and more capital intensive goods, as capital has accumulated with high investment rates over time3. Throughout this process, shifting labor demand creates opportunities for working age population to be employed in jobs moving from lower productivity sectors to higher productivity sectors.

Source: World Development Indicators

The youth unemployment issue has been in the news with respect to the “Arab Spring.” Many youth protesting in the streets have relatively high education levels. A recent World Bank report4 finds that for oil importing countries in the Middle East and North Africa, government sector employment is oversized relative to other middle-income countries, while oil exporters have a high growth sector – oil production—that is not labor intensive. The report concludes “…the number jobs created in the last decade was considerably less than the number needed to address key challenges, such as high youth unemployment, low labor force participation rates, especially among women, and fast –growing labor forces.”5 The emerging new leaders in the Middle East and North Africa are acutely aware of the urgent need to tackle youth unemployment. Indeed, the WDR 2013 on jobs, which is being drafted now and is being shared in outline form with diverse stakeholders, will grapple with this issue, among others.

How the New Structural Economics (NSE) and the Growth Identification and Facilitation Framework (GIFF) can help put young people to work

A successful development strategy that will facilitate the structural change and create job opportunities for youth can be based upon the principles outlined in the New Structural Economics (NSE) and its policy implementation via the Growth Identification and Facilitation Framework6. The NSE highlights that a country’s economic structure is endogenous to its endowment structure; however, the government needs to play a facilitating role in the process of structural change and this role needs to be structured according to clearly defined principles.

First, for an economy to be competitive in both the domestic and international market, it should follow its comparative advantage, as determined by its endowment structure. In the early stage of development, sectors that the economy has comparative advantage will be labor or resource intensive. Examples include light manufacturing, smallholder agriculture, fishing and mining. Only a few activities like mining are likely to be capital intensive in this early stage. In the later stages of development, the competitive sector will become increasingly capital intensive, as capital accumulates thus changing the country’s endowment structure. In the industrial upgrading towards more capital intensive production, infrastructure needs to be improved simultaneously to reduce the firms’ transaction costs, and there is a clear role for government to play in this regard.

Secondly, if a country follows the above principle, its factor endowment upgrading will be fast (due to large profits and a high return to investment), and its industrial structure should be upgraded accordingly. The upgrading entails information (for example, which new industries to invest), coordination (improvement in “hard” (e.g., transport) and “soft” (institutional) infrastructure), and externalities (useful information generated by “first movers”). All of these aspects involve externalities or public (semi-public) goods that the market will not automatically resolve on its own. The government needs to play facilitating role in help the private sector overcome these issues in order to achieve dynamic growth.

A practical approach for the government to operationalize the NSE is laid out in the six steps of the Growth Identification and Facilitation Framework. Without getting into all the details, the six steps are: (i) identify the list of tradable goods and services that have been produced for about 20 years in dynamically growing countries with similar endowment structures and a per capita income that is about 100 percent higher than their own; (ii) among the industries in that list, the government may give priority to those in which some domestic private firms have already entered spontaneously, and try to identify the obstacles that are preventing these firms from upgrading the quality of their products or the barriers that limit entry to those industries by other private firms; (iii) some of those industries in the list may be completely new to domestic firms, and the government could adopt specific measures to encourage firms in the higher-income countries identified in the first step to invest in these industries; (iv) governments should pay close attention to successful self discoveries by private enterprises and provide support to scale up those industries; (v) in developing countries with poor infrastructure and an unfriendly business environment, the government can invest in industrial parks or export processing zones and make the necessary improvements to attract domestic private firms and/or foreign firms that may be willing to invest in the targeted industries; and (vi) the government may also provide limited incentives to domestic pioneer firms or foreign investors that work within the list of industries identified in step 1 in order to compensate for the non-rival, public knowledge created by their investments.

As above data reveal, the youth bulge will be an important demographic phenomenon in developing countries, and especially in Sub-Saharan African countries, in the coming decades. While it is important to increase the employability of young people themselves, it is also essential to facilitate dynamic structural change to create jobs for youth. By doing so, the youth bulge can be transformed into a demographic dividend, and the demographic bomb can be defused.

[1] World Bank, World Development Report 2011: Conflict, Security, and Development. Washington, DC..

[2] See World Bank, 2011, “Striving for Better Jobs: The Challenge of Informality in the Middle East and North Africa.”

[3] There are numerous studies on the productivity of Korean firms. One recent paper studies the pattern of productivity catch-up between Korean and Japanese firms: Moosup Jung, Keun Lee, and Kyoji Fukao, “Total Factor Producitivity of the Korean Firms and Catching Up with the Japanese Firms,” Seoul Journal of Economics, 2008, Vol. 21 (1).

[4] World Bank, 2011, “Striving for Better Jobs: The Challenge of Informality in the Middle East and North Africa.”

[5] Ibid, page 48.

[6] See Justin Yifu Lin, “New Structural Economics: A Framework for Rethinking Development,” World Bank Research Observer, no. 2, Vol. 26 (September 2011), pp. 193-221; Justin Yifu Lin and Celestin Monga, “Growth Identification and Facilitation: the Role of State in the Process of Dynamic Growth”, Development Policy Review, Vol. 29, No. 3 (May 2011), pp. 264-290; and Justin Yifu Lin, 2012, New Structural Economics: A Framework for Rethinking Development and Policy, Washington, DC: World Bank.

Join the Conversation