COVID-19 is not the only pandemic striking India. Eight-year-old Rakesh died of hunger during the national lockdown in March 2020. The 1-year-old son of Sevak Ram succumbed to acute malnourishment in June. These are not isolated cases. India is fighting a dual battle against malnutrition and COVID-19. The lockdown has disrupted access to rations and other essential services, closed schools (cutting off midday meals for children), and led to job losses, putting millions of families in India at even higher risk of extreme poverty and malnutrition.

Even before the pandemic, India accounted for a third of the global burden of malnutrition. In rural areas, stunting, wasting, and impaired immunity are common due to nutrient deficiencies. While India has made progress in maternal and child nutrition in recent years, disparities persist and the COVID-19 pandemic has further accelerated the crisis. The COVID-19 lockdown and the associated economic shocks put formerly food-secure households at increased risk, which will have a direct impact on the nutritional intake of children.

At the same time, the lockdowns have increased the time fathers spend at home and opened opportunities to increase their involvement in child nutrition and development. Earlier diagnostic work conducted in households with small children had established high smartphone penetration and social media usage among young fathers. Could we use this information, coupled with fathers’ increased time with their children, for a rapid intervention to prevent child nutrition from backsliding?

The World Bank’s eMBeD team and Quilt.AI set out to understand whether social media could be used to get fathers motivated and active in ensuring their children’s nutrition. We did this in three steps:

First, we set out to explore the online discourse on child nutrition, with a focus on fathers. What do fathers search for, care about, and talk about? Quilt.AI’s Culture AI was deployed to extract the digital footprint of parents and caregivers in two of India’s poorest and most malnourished states: Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. Data pertaining to 47 million searches and 1,500 unique keywords from 2019-20, blog posts on nutrition, social media uploads, and content consumed by caregivers was analyzed by a team of researchers. We looked at fathers and mothers (based on their online profiles and identification), though we were specifically after fathers. We found:

- The pandemic focused attention on public health and nutrition programs. We found greater awareness about government programs and nutrition agencies in social media and search behavior. For example, between March and May 2020, there was a 93% increase in search interest in government provisions such as the Poshan Abhiyaan and Anganwadis across India, while in Bihar there was a 426% increase (about 4.5 times the national average).

- Together with increased attention, we found expressions of underlying sentiments that the government and nutrition agencies were not doing enough to eradicate malnutrition. We encountered the belief that resources are not properly and equitably distributed, complaints of transparency, and others. In the context of COVID-19, discontent expressed as judgment of insufficient action from officials to mitigate the pandemic-induced nutrition crisis was linked to expressions of loss of trust in authorities.

- Aside from public programs, we found that, although numerous online resources related to child nutrition, the engagement levels of parents and caregivers with such content was low, especially in rural areas. Further, online resources primarily target mothers and ignore fathers. Child nutrition appears to still be considered a matter entrusted to the women of the house. Fathers online chose to engage with other kinds of content, such as news and entertainment.

- Concerns about affordability and accessibility increased during the COVID months. Affordability concerns rose by 56% in Bihar and 46% in Uttar Pradesh, and concerns over availability increasing by 52% in Bihar and 42% in Uttar Pradesh. Popular search terms include “baby food too expensive,” “cheap infant formula,” and “free baby milk powder.”

- The disruption of essential services and government programs have particularly affected efforts to raise awareness among parents in rural areas. Misconceptions about food continue to thrive, and they combine with fear and anxiety related to COVID-19. We find evidence that social norms classify various nutritional food items like eggs as “bad food” due to seasonal concerns. Trending nutrition videos teach people “how to boost immunity in children,” although the information provided in them may not be scientifically proven.

- Caregivers’ online behavior varies in urban and rural areas. Government programs make up a bigger portion of nutrition conversation in rural areas than urban areas. Further, malnutrition is still a deeply political issue and public opinion is largely driven by social media, which has a stronger presence and influence in urban areas. Caregivers in urban areas are also better informed when making food decisions, while community workers are an important source of information for caregivers in rural districts, though their efforts have been severely affected by the pandemic.

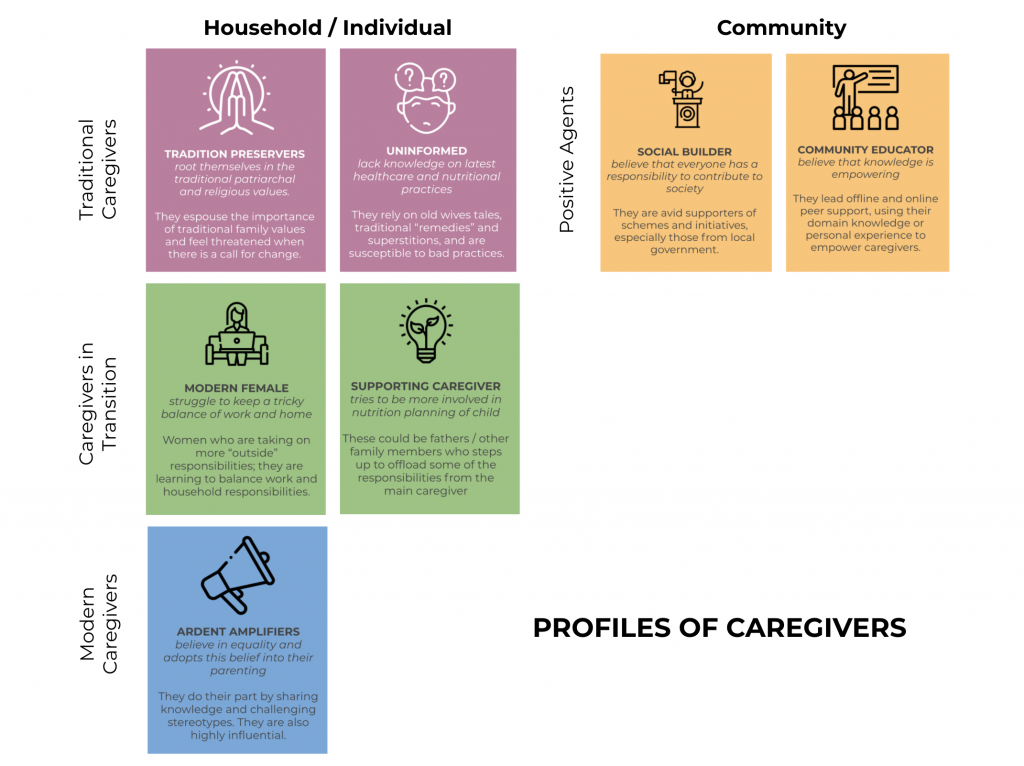

Second, the online discourse was further segmented into seven “types” of personas with distinct characteristics to help gain a nuanced understanding of how caregivers, with different gender, socio-economic and age demographics, express themselves on nutrition, both on social media platforms and search behavior. This population segmentation helped identify which caregiver profiles to target during the social media intervention. We decided to focus on three profiles: Traditional caregivers, caregivers in transition, and modern caregivers, all with specific characteristics (age, gender, location):

Third, we designed a social media intervention to get fathers more involved into child nutrition. We used the profiles to identify specific ways to frame and present messages to fathers under each of these profiles, for a campaign that will target them as they engage with social media for other things.

The pilot campaign is happening now (on Facebook and Instagram) in 52 districts in the states of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. The online campaign’s images and messages cover 14 different topic areas, from expanding the concept of what makes a good provider, to increasing fathers’ role in child feeding (see example below). Some messages provide clear actions fathers can take to engage with their children in food-related activities; others link nutrition with aspects of child development where fathers are more involved, such as cognitive development and educational outcomes. Each topic message has been adapted to appeal to each of the profiles identified. We will look at the campaign’s effects on knowledge, interest, and behaviors.

Pushed by the constraints of COVID-19 regulations, our team had to adapt. Using insights from online profiles and search behavior to inform the design of communications interventions offers an opportunity to tailor interventions when you cannot collect additional data from intended target populations. Pilots like this can also help us unlock insights and overcome barriers to effective social and behavior change interventions, and particularly how to connect people’s online behavior with their “real” life. Stay tuned for our results.

Join the Conversation