When frontline health workers in their U.S. state faced a shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE), the University of Wisconsin’s lab engineers successfully designed and produced a life-saving stock of face shields, which are now being manufactured by Ford. But in many countries of the world, such nimble endeavors are not possible. It is not because of a talent shortage but the absence of adequate digital infrastructure. This is particularly true in the Middle East and North Africa region (MENA), where the existing infrastructure is currently under stress. In a region marked by decades of conflict, the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) is likely to fuel more instability and further widen disparities between those with more robust digital capacity and those without, including the refugee population.

The ongoing global pandemic has forced individuals to physically distance themselves, and “traffic” has shifted from roads and highways onto digital networks, making high speed and reliable internet connections a vital lifeline. Now more than ever, the MENA region runs the risk of falling further behind due to low penetration of “3G-or-greater” mobile connections even in relatively mature markets (see Fig. 1).

Reversing positive trends from before COVID-19, network data also reveal that average internet speeds are currently falling in the region. With the Middle East as a reference point, we aim to outline why these trends are troubling, the extent of the problem, what their underlying causes are, and some steps that can mitigate them.

COVID-19 has rapidly transported us 5 to 10 years into the future, where most interactions move online. Applications such as videoconferencing, accessing cloud services, video streaming, and others, all require high-speed internet access. But data reveals that the burdens of the pandemic have caused existing digital infrastructure to lag due to network congestion.

As internet applications grow progressively complex, they require concomitantly advanced and expansive infrastructure to be used reliably. At present, optical fiber deployed for a broadband wireline connection, or for a wireless 3G mobile connection (or greater, such as 4G or 5G), is considered the minimum level of connection speed necessary to use more advanced internet applications.

Troublingly, even many locations with high-speed internet access see challenges due to COVID-19, caused by insufficient resilience of infrastructure to accommodate high network traffic. They face unreliability in the form of outages, lower speeds, and higher latency, making them suboptimal for high bandwidth applications.

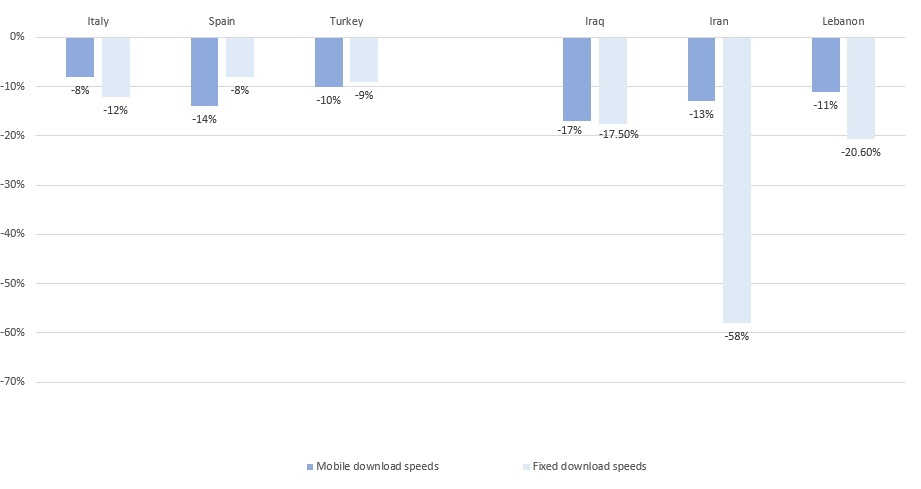

Network data from the countries with high COVID-19 caseloads indicate a disturbing pattern. From March 2 to April 15, mobile and fixed internet download speeds fell in Italy, Spain, and Turkey. Similar trends have begun in the Middle East, and are likely to continue: for instance, from February to March 2020, mobile and fixed internet download speeds fell in Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, and elsewhere (see Fig. 2). This is especially concerning as it reverses trends from 2019, when average connection speeds had been improving modestly in most parts of MENA (see Fig. 3).

The key reasons underlying network congestion are an increased surge in demand at the “last mile” of digital infrastructure, which employs base stations to deliver access to the end user. The shift in daytime peak traffic from commercial areas to residential areas further strains the existing network topology, such as the layout of base stations and other infrastructure equipment.

In the short term, governments must take steps to promote infrastructure sharing, specifically of unused government-owned capacity, and provide more frequency spectrum to operators when available. Moving forward, it will be increasingly important to reform Universal Service Fund policies to respond to the crisis, as well as remove constraints on CAPEX investments in the telecom sector, including rationalizing costs related to infrastructure deployment.

In summary, as our reliance on digital communication increases greatly, existing fault lines in communication networks (limited capacity, inadequate infrastructure, etc.) are further accentuated. The inequities caused by a lack of digital access have been deepened by this crisis, and universal and reliable access to high-speed internet should be achieved before these fissures become irreversible, especially in the most fragile regions of the world.

Join the Conversation