Those unfamiliar with the fast growing emerging economies of East Asia are likely to think that governments in these countries let market forces and capitalism roam free, red in tooth and claw. That was certainly my impression before coming to work in the region, and generally that held at the outset of our work by the group of us that wrote a new World Bank report “East Asia Pacific At Work: Employment, Enterprise and Wellbeing” .

The report shows just how wrong we were. We could be forgiven this impression—many of us had come from assignments in Latin America and the Caribbean or in Europe and Central Asia, where the distortions and rigidities from labor regulation and poorly designed social protection are rife, and where policy makers cast envious looks at the stellar and sustained employment outcomes in East Asia.

Well, it turns out that although they came relatively late to labor regulation and social protection, many governments in the region have entered this arena with gusto. We were surprised to find that, going just by what is written in their labor codes, the average level of employment protection in East Asia is actually higher than the OECD average.

What’s more, there are notable outliers like Indonesia, where workers whose employment is regulated enjoy more employment protection than workers in France, Greece, or Portugal, and only a little less protection than workers in Spain.

Are you ready for more surprises? In China, workers in regulated employment are more difficult to dismiss than in Belgium and Italy. Similarly, reflecting only what is in labor laws, the Philippines has one of the highest average statutory minimum wages in the world: by some measures, it is much higher than in Belgium and France and more generous than in high-income neighbors Australia and New Zealand.

In early stakeholder consultations for the report, a union leader pointed out that the most restrictive regulations are “toothless” since governments have limited capacity to monitor compliance, and most firms have become adept at evading enforcement. It’s a fair point, and raises a valid question that the team grappled with: Do de jure regulations matter de facto?

The World Development Report 2013: Jobs (WDR) argued the debate about these policies absorbs more time and is far more heated than their actual impact on employment outcomes would seem to merit. The report pointed out that most countries avoid extremes of too little and too much regulation and have placed themselves on a “plateau” between these two extreme “cliffs.”

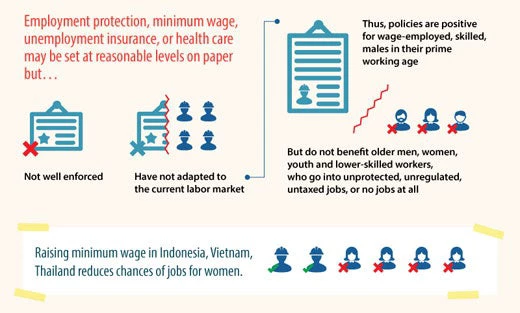

On this plateau, labor policies have a modest impact. But this benign impact of reasonable labor regulation is mainly observed in countries with good administrative and enforcement capacity. When combined with poor capacity, even reasonable labor policies can aggravate the market failures they were designed to overcome, create segmentation and social exclusion.

What’s more, while restrictions on dismissal and wage regulation are being loosened in most middle- and high-income countries, regulation in East Asia is moving in the opposite direction. And as governments become better able to enforce regulations, and firms find it harder to evade, these restrictive levels of regulation will become more binding.

Indeed, for a segment of firms that are already too large to evade detection—many of them international companies most likely to transfer knowledge and skills—onerous levels of regulation are already a problem and, for many, a source of unfair competition from smaller rivals that can still ignore the rules and hire informally.

But in our report, we pose a more fundamental question: As relative newcomers to labor regulation and social protection, why can’t emerging market countries in East Asia Pacific do things differently?

The WDR 2013: Jobs also argued that, even on the safe “plateau”, labor policies tend to redistribute gains toward prime-age men at the expense of women, young people, those who need or prefer to work part time, and self-employed people. Indeed, the evidence from East Asia Pacific shows that rising minimum wages, tight restrictions on dismissal, and high labor taxes hurt the employment prospects of women, young people, and those with fewer skills.

In retrospect, these findings should come as little surprise. The prevailing models of labor regulation and social protection were first conceived in countries and during periods in history when middle-aged men working in full-time dependent employment were the largest group in the labor force. These models have been showing their age in Europe, Latin America and other regions where the profile of working people has become more diverse. They were probably always a bad fit for East Asia Pacific, which has some of the highest rates of labor participation among women and young people, as well as lower levels of full time dependent employment.

In “East Asia Pacific at Work” we argue that the relatively short history of labor market intervention and social protection in East Asia Pacific is an opportunity. There are fewer ‘sacred cows’ and entrenched interests than in other low and middle income countries. Our report suggests ways in which governments can be more active to sustain the wellbeing people can expect from work, but by creating new models of labor regulation and social protection that benefit all working people, no matter how or where they work.

Join the Conversation