新型冠状病毒爆发期间,在印度尼西亚雅加达一家社区卫生中心,一名妇女怀抱自己的孩子。 (图片:Achmad /世界银行)

新型冠状病毒爆发期间,在印度尼西亚雅加达一家社区卫生中心,一名妇女怀抱自己的孩子。 (图片:Achmad /世界银行)

Since early May 2020, many countries in the East Asia and Pacific (EAP) region have conducted high-frequency household phone surveys to monitor the socio-economic impacts of COVID-19 and to inform policy responses to the crisis. While country-specific analysis is available, it is useful to take a regional look at common patterns.

This data dashboard displays common indicators of the World Bank’s EAP regional high-frequency phone surveys conducted from May to June 2020 across seven countries. The dashboard will be periodically updated with additional surveys and further rounds of data.

In this blog post, we will share six key findings from these household surveys, which informed the background paper for the October 2020 edition of the EAP Economic Update. The findings cover employment, income, coping strategies, impacts on human capital, and how the crisis has differed along gender lines.

1. Negative employment impacts have generally been large and widespread – income losses even more so – but some countries have fared worse than others.

A substantial share of workers was forced to stop working or change jobs due to the pandemic. The magnitude of employment losses or disruptions varied across countries, with Myanmar facing large losses and Vietnam experiencing comparatively low losses (Figure 1A). Reductions in household income were even more widespread, as a significant share of workers remained employed but faced earning losses due to the crisis (Figure 1B). Declines in both domestic and international remittances have also been extensive across the sample of countries for which survey data are available, with as much as 75 percent of households relying on these transfers experiencing reductions in remittance.

Figure 1. Employment losses were large in some countries, whereas losses in earnings were widespread

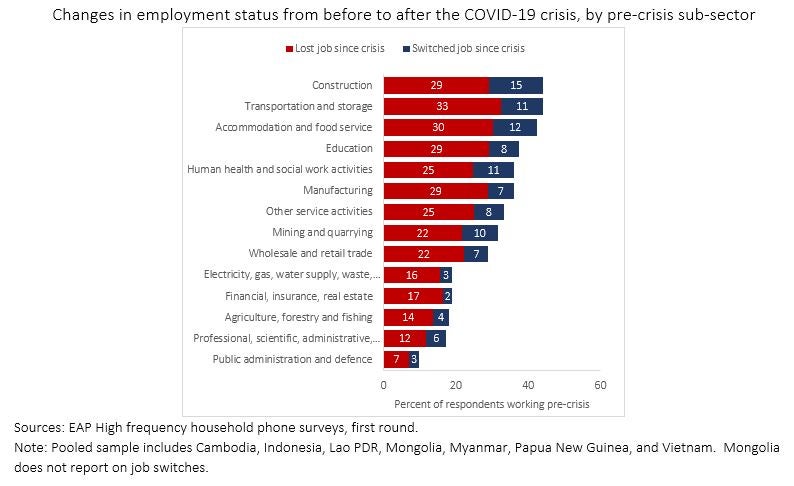

2. Workers in key non-farm sectors, predominantly living in urban areas, were more likely to experience employment shocks.

Job losses and switches were more prevalent among those working in sectors such as transportation, accommodation and food services, and construction (Figure 2). These activities tend to have relatively higher rates of informality and be less adaptable to work-from-home arrangements. Since participation in these sectors is often concentrated in urban areas, urban residents in Indonesia, Mongolia, and Vietnam were more prone to employment shocks than rural residents. However, in largely rural countries, such as Cambodia, Myanmar, and Papua New Guinea (PNG), rural households were also hard hit – both due to relatively high rural employment in affected non-agricultural sectors and negative impacts on the agricultural sector.

Figure 2. The contraction has led to a loss of jobs in services and industries

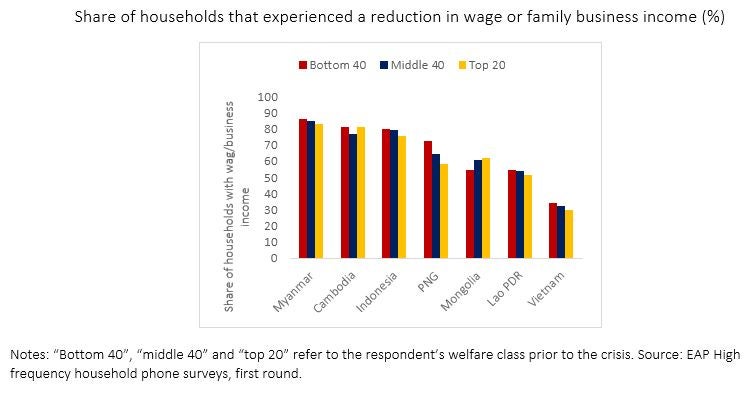

3. Income shocks have affected households across the welfare distribution.

In most countries, key non-agricultural sectors were hit harder than the agricultural sector. This means a significant share of better-off households also experienced reductions in income (Figure 3). At the same, some evidence suggests that, once we control for observable factors, wealthier, more educated workers may have been less vulnerable to shocks. This is because they are more likely to work in formal sector occupations, which may be more adaptable to work-from-home options.

Figure 3. COVID-19-related income losses from wage employment and family businesses have been widespread in most countries

4. To deal with impacts of the crisis, many households lowered food consumption, contributing to increased food insecurity in some countries.

Reducing household consumption, especially on food, was a common coping strategy among households. This is the case of more than half of households in Cambodia, Indonesia, and Myanmar. Households that experienced income losses were significantly more likely to do so than those that did not (Figure 4). Such drastic coping strategies may have resulted in greater incidence of food insecurity: Reducing food consumption is strongly correlated with a shortage of food, eating less than usual, and going hungry. While there have been signs of improvement since June, the rise in food insecurity could have lasting effects on people’s health and economic productivity, particularly among poorer households.

Figure 4. Lowering food expenditure was a common coping strategy, especially among those that lost income

5. The crisis has had adverse impacts on education and health, which have been particularly detrimental for vulnerable groups.

Widespread school closures have resulted in significant disruptions in learning. Efforts to improve remote learning have varied in scale and type across countries, with some countries like Vietnam relying on online/mobile platforms while others such as Mongolia relying on television programs (Figure 5). To the extent that many remote learning activities require access to key technology such as the internet or a phone, poorer children or those living in remote areas are less likely to engage in distance learning in many countries.

Figure 5. Most children remained engaged in educational activities

6. Women have generally fared worse in the crisis than their male counterparts.

Across all sampled countries, women were more likely than men to have lost their job with the onset of the crisis (Figure 6), even considering differences in age and education. This is partially due to higher employment among women in service sectors such as retail and accommodation and food services that were hard hit by containment measures. We also found that female-headed households are more likely than male-headed households to rely on remittances, which have seen broad reductions, and in some countries, to experience food insecurity and limited access to health services.

Figure 6. Female workers are more likely to have lost their job and their male counterparts

As governments in East Asia and Pacific implement support measures and economic activities resume, signs of recovery in employment and income are visible. More recent studies and data from subsequent rounds of the high-frequency surveys indicate that some of the people who stopped working in the early months of the crisis are returning to their jobs, although with some cutbacks in hours and wages. Continued monitoring through data collection will help us understand whether the impacts on the economic activities of households will have lasting effects on their wellbeing. Stay tuned for key indicators on employment, income, food security, and more on the regional data dashboard, which will be updated with further rounds of data.

READ MORE

Join the Conversation