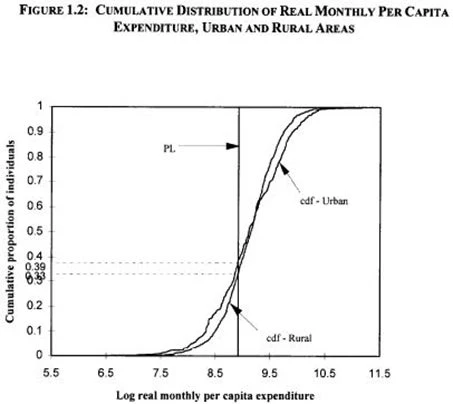

In 1996, Mongolia’s GDP growth declined to 2.2% in real terms and consumer price inflation jumped back up to nearly 47%. The previous year had seen the launch of a project on Poverty Alleviation for Vulnerable Groups, a project which called for a deeper understanding of poverty in Mongolia. In 1996, Mongolia - Poverty Assessment in a Transition Economy was released. This was the first poverty assessment for Mongolia to be based primarily on the Living Standard Measurement Survey (LSMS). The poverty assessment sought to provide an in-depth understanding of the economic, demographic, regional and social characteristics of the poor, and to promote poverty reduction as an explicit objective in the formulation of public policy and resource allocation.

The rationale for the LSMS approach is as relevant today as it was then: “An understanding of the dynamics of poverty is a key to effective policy formulation and program interventions. Toward this end, it is imperative for the government to enhance its poverty monitoring capacity both in terms of household survey implementation and analysis of such data.” (Twenty years later, the World Bank continues to work with the National Statistical Office on poverty measurement and analysis.) Looking forward, and noting the empirical link between job growth and poverty, the report highlighted that “the unemployed poor would be the primary beneficiaries from new job openings and the continued expansion of the informal sector.” Exactly how much the expansion informal sector was contributing to poverty reduction would be analyzed in the coming years.

By 1996 the early privatization programs had run their course, although residual state shares were still held in many companies and there were many others that were still state-owned or subsidized. A detailed report titled Mongolia Public Enterprise Review: Halfway Through Reforms (PER) argued that public enterprises had become an increasing burden on the economy and have been the main recipients of government-directed loans from the banking system. Moreover, the report argued that budgetary subsidies to public enterprises are large and rising, and that public enterprises in energy had arrears to other enterprises, a tangle that would need to be sorted out.

“Public enterprises have become a drag on growth and a major impediment to further stabilization. Without subsidies to public enterprises, Mongolia would have a budget deficit of only one-third its actual size in 1995. The dismal performance of public enterprises is therefore threatening further progress in macroeconomic stabilization. Loans from the budget and commercial banks to non-performing public enterprises crowd out private enterprises. Moreover, loan defaults have crippled the banks, and forced them to charge unsustainably high interest margins on their lending. This has virtually wiped out term lending.”

To put the size of subsidies in perspective, the PER compared the size of the subsidies to the total spending on education, health and social security, and found that the subsidies exceed each of these other spending priorities by a considerable margin—wouldn’t the resources be better spent on health, education, or social security?

While the analytical advances in 1996 helped inform policy making in poverty alleviation and public enterprise reform, Mongolia’s infrastructure still needed critical financing. In 1996, the Coal Project was approved to reverse the decline in Mongolia's coal production by increasing sustainable production levels at the Baganuur mine and improving policies for management of the sector.The year 1996 also proved to be a pivotal one for the World Bank globally. At the Annual Meetings that year, the President of the World Bank Group, James D. Wolfensohn said: “… we must tackle the issue of economic and financial efficiency. But we also need to address transparency, accountability, and institutional capacity. And let’s not mince words: we need to deal with the cancer of corruption.” In the years to come, addressing corruption and governance weaknesses as the development challenges they are would become increasingly important for the World Bank and the development community.

Tomorrow we will look at 1997, prospects for growth, and the opening of the first IFC office in Mongolia.

Prepared in collaboration with Ulziimaa Erdene, Pagma Genden, and Tungalag Chuluun.

(Please follow our 25 years in 25 days journey here and on twitter with the hashtag #WBG_Mongolia25th)

Join the Conversation