Agriculture played a key role by driving growth in the early stages of industrialization. It also contributed to reducing rural poverty by including smallholders into modern food markets and creating jobs in agriculture. Nonetheless, poverty in developing East Asia is still overwhelmingly rural, reflecting a mismatch between agriculture’s shares of GDP and employment.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on WDI data.

As incomes rise and countries urbanize, the composition of domestic food expenditure is shifting from staples to meat, horticulture and processed foods. Thus, while today’s East Asian developing economies transform, the nature of their agricultural sectors is also changing.

Measuring regulations

The World Bank Group’s Enabling the Business of Agriculture (EBA) project measures regulatory good practices and transaction costs affecting agribusinesses. EBA indicators cover a range of regulatory domains pertaining to seed, fertilizer, agricultural machinery, water, access to markets, finance, transport, information and communication technology (ICT). For each of these areas EBA indicators provide an aggregate picture of how supportive regulation is for agribusinesses. A newly released policy note analyzes seven East Asia and Pacific countries including Cambodia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Thailand, the Philippines, and Vietnam.

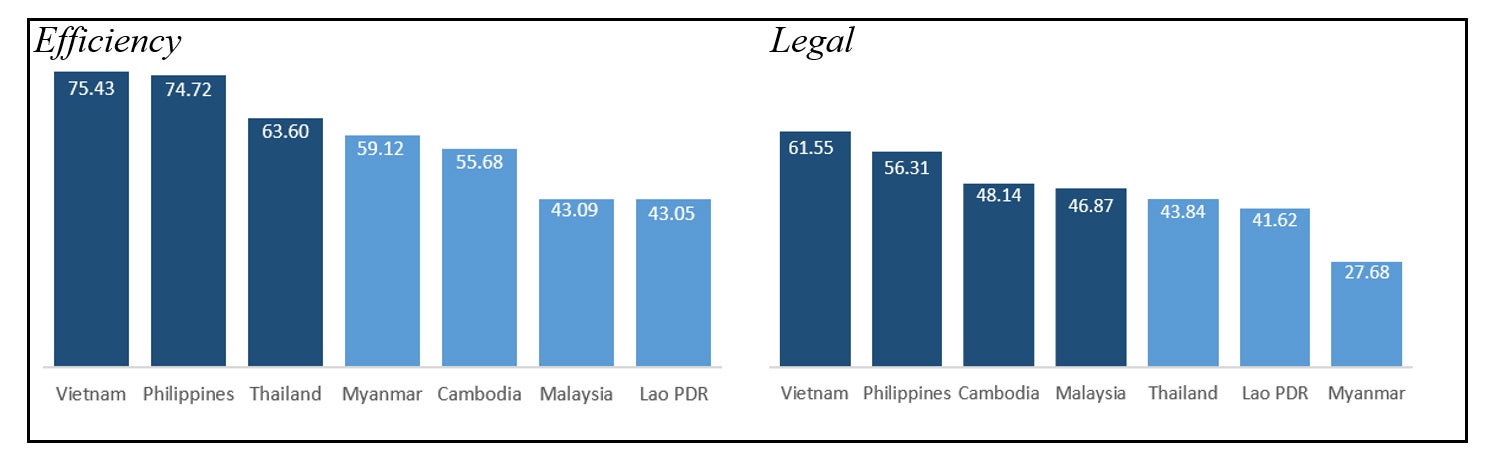

EBA indicators assess regulation on two complementary dimensions. On the one hand, legal indicators reflect the number of regulatory good practices that countries enact to correct market failures. This may include, for example, plant protection regulations or labelling requirements for fertilizers. On the other hand, efficiency indicators measure the transaction costs regulations impose on businesses such as time and cost to register a tractor or obtain a trucking license.

Most regulatory constraints to agricultural development in East Asian economies pertain to the legal dimension, where the region scores second to last.

Note: OECD- High income OECD countries, LAC - Latin America & Caribbean, ECA- Europe & Central Asia,

MENA-Middle East & North Africa, EAP - East Asia & Pacific, SSA-Sub-Saharan Africa, SA- South Asia.

Country-level scores highlight the diversity of agricultural regulation in East Asia, with Vietnam displaying the most supportive framework. This is reflected in Vietnam’s good regulatory practices such as allowing water permit transfers among farmers and abolishing quotas on cross-border transport licenses. Moreover, it is supported by efficient systems. For example, it requires only 15 days to register a chemical fertilizer product in Vietnam, which is the second best performance across the 62 countries covered by EBA—chemical fertilizer registration is fastest in Uruguay. In contrast, Myanmar displays the least supportive regulatory framework, with particularly weak laws on plant protection and pest control and a lack of rules on tractor standards and water permits.

Figure 2. EBA Scores by Country

Rising incomes and urbanization in East Asia are shifting the composition of domestic food expenditure from basic and unprocessed staple foods to meat, horticulture and processed foods. To take full advantage of these emerging trade opportunities policy makers should seize the opportunity to support agribusinesses with effective regulations.

Join the Conversation