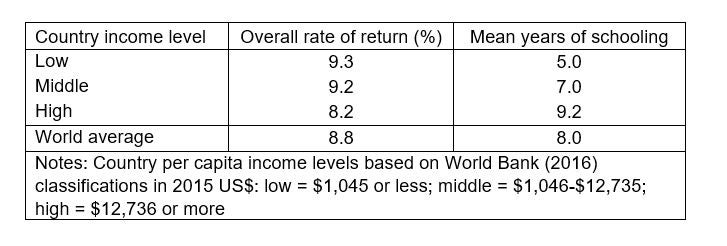

The result—a 9 percent average individual return for one extra year of schooling globally, or in other words, 9 percent increase in hourly earnings—is staggering, especially when compared to other investment options available. One such investment many people choose to invest in are United State stocks and bonds. However, when we learned that investors over a five-decade period from the mid-1960s collected only a mere 2.4 percent return, investing in education looks even more solid.

Our literature review [i], which was published this month, found several key take-aways that we believe can offer useful guidance to policymakers and education practitioners alike:

- While the average global return is 9 percent, low-income countries have an even higher return—9.3 percent on average.

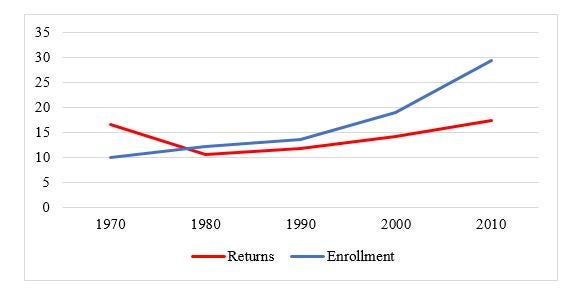

- Private returns to higher education have increased over time, signaling that tertiary education is a good private investment. However, given that most of the benefits of a higher education degree go to the graduate, higher education is not a public good. While countries across all income levels need higher education graduates, before increasing university funding, authorities need to address issues of financing and equity . At the policy level, there need to be incentives for the efficient and equitable use of funds targeting higher education .

- Social returns to schooling—or the costs and benefits to society of investing in education, which include the opportunity cost of having people not participating in the labor market and the full cost of the provision of education—also remain high, above 10 percent at the secondary and higher education levels.

- Women continue to experience higher average rates of return to schooling—nearly 10 percent, compared to 8 percent for men - reinforcing the importance of girls’ education from both individual as well as social perspectives.

- Private and social returns are higher in low-income countries indicating that for these economies education investments should be prioritized.

- Private sector employees enjoy higher returns to education than those in the public sector, highlighting the productive value of education in contributing to the growth of economies.

General Conclusions

Overall, despite the massive influx of new students into the global education system in recent decades, education remains a solid investment. Even as more graduates “flood” the market, being a skilled worker has become ever more vital, and human capital continues to be highly valued.

Recent research indicates that the remarkable social rates of return reported above are still under-estimated because of the omission of several externalities. By putting a monetary value on just one externality of education – reduced mortality – the social rate of return to investment in one extra year of schooling in low-income countries skyrockets to 16 percent , relative to 11 percent based solely on earnings differentials.

Implications

We believe that these figures provide an important guide for policymakers tasked with allocating education budgets. As the data shows, countries that have yet to achieve universal primary education should prioritize basic education, while countries with low rates of girls’ enrollment should focus on educational opportunities for women . And in countries where students struggle to pay for higher education—despite the high returns for investment that they would later enjoy—policies need to focus on tuition assistance and other forms of support that would enable poorer students to enroll in tertiary education.

When in Doubt, Estimate!

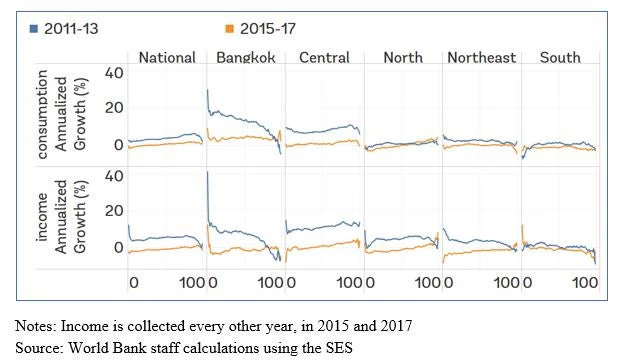

These estimates are important, but countries that lack more specific information about their own education systems should invest in collecting country-level data. There is no substitute for granular data, which provides critical clues for where to best invest and focus precious resources.

This work is ongoing, with upcoming new estimates on the effects of the quality of schooling. Although there are plenty of macro-level studies in this respect, micro-level analyses on the returns to investing in specific school quality inputs – like student-teacher ratio – are still emerging.

The rate of return patterns found in previous analyses are upheld and reinforced by our research. When taking into consideration efficiency in the use of resources, spending on human capital is one of the best investments a country can make in its future.

This blog draws from research conducted jointly by Prof. George Psacharopoulos and Harry A. Patrinos.

Join the Conversation