The World Bank is currently working with a few countries that are planning for the procurement of lots of digital learning materials. In some cases, these are billed as 'e-textbooks', replacing in part existing paper-based materials; in other cases, these are meant to complement existing curricular materials. In pretty much all cases, this is happening as a result of past, on-going or upcoming large scale procurements of lots of ICT equipment. Once you have your schools connected and lots of devices (PCs, laptops, tablets) in the hands of teachers and students, it can be rather useful to have educational content that runs on whatever gadgets you have introduced into to help aid and support teaching and learning. In this regard, we have been pleased to note fewer countries pursuing one of the prominent worst practices in ICT use in education that we identified a few years ago: "Think about educational content only after you have rolled out your hardware."

The World Bank is currently working with a few countries that are planning for the procurement of lots of digital learning materials. In some cases, these are billed as 'e-textbooks', replacing in part existing paper-based materials; in other cases, these are meant to complement existing curricular materials. In pretty much all cases, this is happening as a result of past, on-going or upcoming large scale procurements of lots of ICT equipment. Once you have your schools connected and lots of devices (PCs, laptops, tablets) in the hands of teachers and students, it can be rather useful to have educational content that runs on whatever gadgets you have introduced into to help aid and support teaching and learning. In this regard, we have been pleased to note fewer countries pursuing one of the prominent worst practices in ICT use in education that we identified a few years ago: "Think about educational content only after you have rolled out your hardware."

At least initially, many education authorities in middle- and low-income countries seem to approach the large-scale procurement of digital learning materials in much the same way that they viewed purchases of textbooks in the past. On its face, this is quite natural: If you have tried and tested systems in place to buy textbooks, why not use them to buy 'e-textbooks' as well? (We'll leave aside for a moment questions about whether such systems to procure textbooks actually worked well -- that's another discussion!) As with many things that have to do with technology in some way, things become a little more complicated the more experience you have wrestling with them.

Pretty much all schools with decent connectivity access free educational content on the Internet. (Indeed, this is one reason that schools are connected in the first place!) Many schools buy (or are given) subscriptions to web sites that contain learning materials and, at the district, school, classroom or even individual teacher level, digital educational content of various types is regularly bought and used in ad hoc ways. As ICT use becomes more widespread across many education systems in middle- and low-income countries, many education ministries prefer to have schools accessing content from one central place that is in some way overseen by the ministry itself. There are many reasons for this impulse -- the inevitable desire of a bureaucracy for control is one, of course, but there are also perhaps more legitimate educational reasons related to ensuring quality, child digital safety, security issues, clear linkages between educational content and curricular objectives, privacy, a desire to link teacher professional development activities to specific educational content, concerns about intellectual property violations, and cost savings through bulk purchases, to name just a few.

If you are acquiring and using digital educational content, what is the nature of that content?

Increasingly, it is 'free'. By free, we mean here that its use comes at no cost, either because it is it is available as a so-called 'open education resource', because the copyright holder does not charge for its use, or because it is pirated.

(For what it's worth, I notice the use of pirated content in schools I visit more often now that I did in the past; I have *always* remarked to myself on just how widespread the use of pirated software is in many schools. Mentioning this here is not meant to condone such activities -- far from it! -- just to acknowledge that this is a practical reality in many places, and that suppliers of educational content and education systems alike have to contend with this reality.)

In some cases, 'free' also refers to the fact that users can adapt, modify and redistribute this content. My goal in talking about 'free' here is not meant to start a conversation about the merits of open educational resources, or about proprietary vs. 'open' content. There are plenty of other places where you can tap into vibrant discussions of this sort on the web. Rather, it is to highlight the cost issue is not what it once was.

Increasingly, certain digital content has rather complicated 'ownership'. A piece of content, for example, may be 'owned' by a publisher, but include within it content licensed for a fee from a third party, and well as content licensed without a fee from a third party under a Creative Commons license. Not sure what this means? Imagine a 'page' in an electronic textbook that you bought from a publisher that incorporates a graph that was created by university professor and made available for educational use under a Creative Commons license and an accompanying video that the publisher had licensed for use from a news organization. When a government 'buys' such content, what exactly is it buying?

Sometimes, the content is delivered, or made available, in a way that is closely linked to the use of certain devices or certain technologies but which can make it difficult to utilize this content once such specific devices or technologies are no longer used. What good is it if you 'own' content but you no longer have devices on which you can access this content?

Recognizing such things, some places are exploring a decidedly pragmatic approach. They take the position that they are buying not a free-standing product (like they did with "a textbook"), but rather that they are buying what is essentially a time-bound service ("access to what a textbook contains"). We need digital materials to use as part of our biology instruction, a ministry of education might say. We'll buy some that we can use over the next five years. At that point, we'll looking into buying some more to use over the subsequent five years.

What does this mean, why might it be an important and useful distinction, and is this a prudent course of action?

Let's take the last part first: Whether this is prudent depends on your particular circumstances. Based on what I've observed in practice and through talking with education ministries making decisions in this regard, there is no one correct approach to this issue. In addition, technological changes can regularly complicate whatever approach you are currently taking.

In some cases, we find that the private sector is starting, for better or for worse, to push ministries of education to think in terms of services versus products.

In order to understand what is happening in various related markets around the world, we meet irregularly (but often) with educational publishers to inform ourselves about what they are doing, and what trends they might be seeing. A few years ago, I began to notice a change in the language used by some of the educational publishers with whom I was speaking. We are no longer just selling books, some companies would tell us, but rather learning management systems [or, in some very interesting cases, assessment systems] in which educational content is inextricably embedded. Like their counterparts in 'content' industries like in the music industry found, and which the video entertainment industry is currently finding, many educational publishers are confronting an emerging reality that electronic content delivery is quickly re-shaping their longstanding business models, whether they like it or not. Embedding content into some sort of learning management system, especially when this is closely linked with formative assessment tools, is one way for publishers to respond to challenges represented by piracy and the 'open content' movement. (While there are lots of 'open educational resources' in wide use around the world, and I often see open source learning management systems like Moodle used in school systems, I have never seen a dedicated 'open source educational assessment system' in widespread use in multiple countries. I don't doubt that such things exist -- I have had people pitch them to me -- but I have never actually encountered such a thing being used in a school I have visited.) Monthly or yearly subscriptions do tend to have more regular cash flow consequences than large, one-off sales of textbooks or other types of non-digital learning materials. (As many publishers evolve into what look in many ways an awful lot like IT or software firms, there are obvious parallels here with the steady growth in business models deployed to help service corporate clients using a 'software as a service' model.) As ministries of education struggle with challenges related to running their own data centers to host and serve digital educational content to lots of schools at once, many are wondering if it might not be more cost effective to off-load this responsibility to some other organization -- where publishers have close links to firms that can do just this, outsourcing this work starts to appear more attractive to some educational authorities.

Such arrangements can have numerous advantages from the perspective of governments. Payments can be smoothed out over time, and not done as a large 'lump sum' as when, for example, textbooks are delivered. An education ministry is freed from having to worry about, plan for, and react to the inevitable changes in technology that happen regularly, and can instead focus on an area which is presumably its core competence: running a school system and educating children. But this sort of arrangement carries with it some very clear disadvantages and drawbacks as well.

At a basic level, there is a challenge when trying to do something that you have not done before, where your past experience does not offer ready guides for your future actions. Some specific challenges that we see ministries of education struggling with, especially in middle income countries, include:

What happens when a contract is complete, and you don't 'own' any of the content you have been using?

When you buy textbooks, they last a long time. If you need to make them last another year beyond what you originally envisaged, you can probably make this happen. (This is not always a good thing: Some countries are infamous for continuing to use textbooks that are long out of date.) If you do insert a sort of 'rent-to-own' clause into your contract that says the government will own the content at end of the contract, how can ensure that you do in fact have full ownership rights to the content you have purchased (especially where third-party licensing may be involved) and that the content itself still is of value, especially if it is deeply embedded into a learning management or assessment system to which you may not have the rights, or which needs to be updated (or indeed is obsolete).

How can you avoid 'lock-in' of various sorts?

This includes being locked into not only the products and services of a particular company, but also to particular technologies.

What if you buy content, or access to content, drawn not only from a publisher's own intellectual property, but which also includes content that is freely available, and which the publisher itself simply re-packaged and did not pay for -- should you care?

Some places are asking themselves the extent to which the value is in the individual content itself, versus the curation and sequencing of such content, linked to specific curricular objectives (and in some cases, specific means of formative assessment).

How can you ensure that you are getting value for money?

Most places have pretty widely known and transparent historical and market benchmarks for the costs of textbooks. What benchmarks should you use for costs in fields changing as quickly as that of digital content and information technology?

How can you ensure the privacy of teachers and students who are regularly accessing digital learning content maintained by a third party, or which contains potentially personally identifiable information which is accessible by third parties?

These are just five of dozens of such questions that we see ministries of education (and the finance ministries who fund them) asking, and struggling with, around the world as they embark on large scale purchases of digital education content. In almost all cases in which I have been involved, initial discussions almost always consider the procurement of digital learning content to be a product. Over time, however, some places are wondering if in fact it might be more useful to consider such things to be a service, challenging both existing approaches to procurement, and the nature of what it is exactly that schools are buying when they acquire new educational content.

----

On somewhat related notes, here are two recent reports that you may have missed:

The 2012 Paris OER Declaration was formally adopted and released at the 2012 World Open Educational Resources (OER) Congress, held back in June at UNESCO headquarters in Paris. The OER movement has helped to re-shape opinion in various ways in many ministries of education about intellectual property rights and the use of educational materials.

Released this week by the State Educational Technology Directors Association in the United States, Out of Print: Reimagining the K-12 Textbook in a Digital Age, highlights "the sea change underway in the multi‐billion dollar U.S. K‐12 instructional materials market enabled by recent technology and intellectual property rights innovations." It begins by stating:

"Technological innovation is driving fundamental changes in all aspects of our lives. This is especially true of digital content, as our use of e-books, downloadable music, streaming television and movies, and online social networks has exploded. However, the explosive growth in our use of digital content seems so far to have eluded many of the 50 million students enrolled in public K-12 education. In spite of the fact that states and districts spend $5.5 billion a year in core instructional content, many students are still using textbooks made up of content that is 7 to 10 years old. In 2012, it is still the exception—not the norm—that schools choose to use digital content, which could be updated much more frequently, or opt to use the multitude of high-quality online resources available as a primary source for teaching and learning.

The reasons are many, but the result is this: Too few schools are exploiting digital instructional content for all of its benefits. While many in education continue to perpetuate the decades-old textbook-centric approach to providing students and teachers with instructional materials, the gap is widening between what technology allows us to do in our lives—how we communicate, work, learn, and play—and how we’re educating our kids.

Nonetheless, it is not a question if the reimagining of the textbook will permeate all of education, but only a matter of how and how fast."

Whether or not you ultimately agree or disagree with the messages, conclusions and recommendations contained in these two documents, reading them may force you to confront some of your thoughts, practices and assumptions related to the creation, acquisition and use of digital learning materials. In the end, you may decide that how you have been doing things in the past is still a useful template for action as you move forward. Fair enough. That said, forcing yourself to challenge your existing practices and assumptions from time to time -- especially if you are about to spend a *lot* of public monies -- perhaps isn't such a bad thing either.

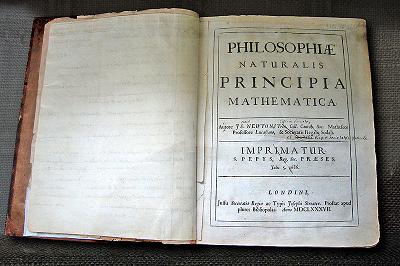

Please note: The image used at the top of this blog post of a sculpture which stood across from the Humboldt Universität during the 2006 World Cup in Germany as part of teh Berliner Walk of Ideas ("tell me again why we didn't buy the digital version?") comes from Wikipedian Lienhard Schulz via Wikimedia Commons and is used according to the terms of its Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 Generic license. The sculpture itself, "Der moderne Buchdruck", is meant to commemorate Johannes Gutenberg. The second image used in this blog post of Sir Isaac newton's copy of Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica ("a decidedly old school textbook") is © Andrew Dunn 2004 and comes via Wikimedia Commons. It is used here according to the terms of its Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license.

Join the Conversation