A girl plays with an abacus at the New Salome Ureña School in the Capotillo neighborhood in the city of Santo Domingo on June 25, 2021, in the Dominican Republic. Photo: Orlando Barría

A girl plays with an abacus at the New Salome Ureña School in the Capotillo neighborhood in the city of Santo Domingo on June 25, 2021, in the Dominican Republic. Photo: Orlando Barría

Seven out of ten children in Low- and Middle-income Countries (LMICs) don’t read with understanding by age 10.[1] No one doubts the urgency of reversing this tragic failure of learning, but what exactly should be done? There is no better time than World Literacy Day to ask the questions whose answers point to the best path to immediate improvement for hundreds of millions of children.

Literacy brings access to knowledge, work, social interaction, and political participation. There is a large body of scientific knowledge about how children learn to read and how they can best be taught. The depth of this scientific knowledge makes the exclusion of so many from the economic and social benefits of literacy particularly shocking. Science tells us that virtually all children are capable of learning to read, so why aren’t they learning, and what should be done to change course?

The best answer comes when we break reading down into two main component skills. Reading with comprehension is a complex skill, integrating a variety of pre-requisite abilities. The most important skills for the beginning reader are (a) the ability to understand spoken language; and (b) the ability to map printed words onto spoken language. Reading specialists call the former “comprehension” and the latter “decoding.” Whatever you call them, they obey a simple law: in order to comprehend what you are reading, you have to “get the print off the page” in the first place. Readers turn printed words on the page into spoken words in their heads.

Research shows that 99% of the variation in children’s reading comprehension comes down to these two component skills. However, emerging evidence indicates that most children in LMICs are not able to decode printed words. They may know a word if they hear it, but they cannot quickly and easily recognize that same word on the page and then turn it into “spoken language in their heads.” They fail because they have not gotten enough instruction and practice in mapping letters to sounds and sounds to letters.

How do we know this? We recently analyzed over 6000 scores from more than 300 reading assessments in 122 languages from 62 low- and middle-income countries. The data shows that students are failing to master basic decoding. They don’t recognize enough letters nor can they automatically say the sounds these letters make (see Fig. 1 below).

When children were asked questions orally, they are three times as likely to answer them correctly as when we give them the questions printed on paper (see Fig. 2 below). In short, they struggle to unstick the print from the page.

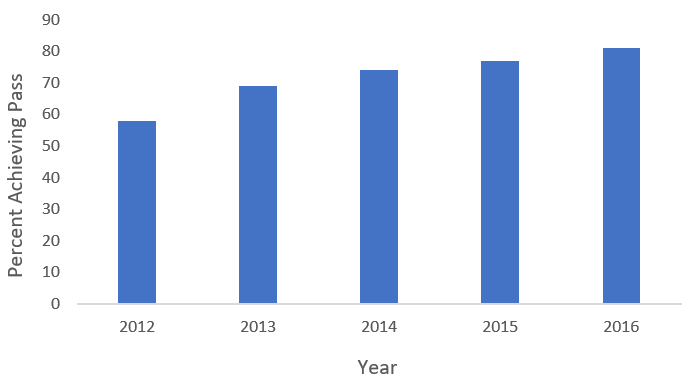

The hopeful news is that lots is now known about how to teach decoding skills, and we also know how to assess whether that teaching is working. In 2012, England instituted “universal phonics screening” to make sure kids know all their letters and sounds. Results showed dramatic year-on-year improvements, including substantial gains for those children living in England’s 10 most deprived counties.

Data source: find-npd-data.education.gov.uk

Great progress can be made with a few dozen hours of teaching, and massive changes have been seen when doing 1-2 hours per school day of good instruction for a year or more. There are only so many letters in the alphabet, and only so many sounds they make. Improving language ability, vocabulary, and other skills for comprehension is a never-ending task, but one that you can best do once your decoding skills are in place. So by making progress on decoding, mental space and teaching time are freed for the more challenging aspects of becoming a good reader.

If one thing is clear from the science of reading, it’s that good instruction works. Time after time, when kids receive enough instruction focused on the real challenges of learning to read, they make progress. Two hours a day of good core classroom instruction leads to most kids becoming good readers. In low- and middle-income countries, students very seldom get even one hour a day.

So on World Literacy Day, let’s be sure that all of us who care about literacy—policymakers, teachers, advocates—ask these fundamental questions: Have kids mastered their letters and sounds? Can they quickly and easily unstick the print from the page? If the answer is no, then what is missing from their school instruction that prevents them from learning this most learnable skill in literacy? The task of improving literacy is large, but significant gains await if we can ask these questions and act on our answers.

[1] [Estimates from June 2022 State of Global Learning Poverty Update https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/education/publication/state-of-global-learning-poverty]

Join the Conversation