While I have no data to cite here (perhaps this is an idea that could be explored by an enterprising PhD student?), it is my strong suspicion, based on years of observation and work with groups introducing new technologies into education systems and communities in poor and middle income countries, that a 'Matthew Effect in Educational Technology' is observable -- and worth considering.

Just what is a 'Matthew Effect' -- and why should we care about it?

Almost a half-century ago, the sociologist Robert Merton observed (here's the original paper [pdf]) that famous scientists often get more credit for a research finding than a lesser (or un)known scientist does, even where the work of both scientists is very similar. He labeled this phenomenon the 'Matthew Effect', after a verse in the Bible (Book of Matthew 25:29) which roughly translates as 'the rich get richer'. In the words of the sociologist Daniel Rigbey, who wrote a book on the subject:

"Matthew effects tend to confer further advantages on the already-advantaged, other things equal. Of course, other things are never entirely equal. Multiple interacting factors are at play in a complex and connected world. Nonetheless, more than forty years of research findings suggest that Matthew effects are real and potentially powerful determinants of social outcomes in their own right, and especially when they are not countervailed. We simply cannot understand the dynamics of social inequalities in the world today without taking Matthew effects seriously into account."

Following Merton, Keith Stanovich spoke about a Matthew Effect in an educational context, noting that early successes in developing reading skills usually lead to greater successes with reading -- and thus with learning other new skills that build on the existence of good reading skills going forward.

How does this relate to ICT use in education?

Mark Warschauer, for one, has talked about how technology can help good schools become even better (see for example, his paper Laptops and Literacy [pdf], which draws on more extensive research he presented in a book of the same name). In a series of publications [pdf], researchers at the OECD have warned that "the digital divide in education goes beyond the issue of access to technology. A second digital divide separates those with the competencies and skills to benefit from computer use from those without."

Just who are those with the competencies and skills most likely to benefit from the use of ICTs in schools? It might be, of course, those who already have computers and other ICT devices (at home -- or in their backpacks). Kids from more educated families. Richer kids. Better educated kids, growing up in functional families in functional communities. Kids with good teachers in good schools. It may also be the kids who fit none of those categories but who are 'cognitively exceptional' (or, put another way, 'wicked smart'). When I see experiments that do things like, for example, drop computing devices into remote, poor communities in disadvantaged parts of the world, followed months later by anecdotes about the 'impact' that such devices have had on the education of certain of the children in these villages, I do wonder to what extent people just might be selectively observing how the most 'cognitively exceptional' kids were able to take advantage of the new tools. (A colleague of mine once joked that certain programs of this sort might represent one -- rather expensive! -- method of identifying the 'gifted and talented' in poor, isolated rural communities in Africa and Asia.) This is not to argue that such programs are bad -- or good! -- just that we need to be careful about how we interpret the professed related 'results'.

The Matthew Effect in Educational Technology does not apply only to students, of course. Consider the case of an overwhelmed (and ill-prepared) teacher working with students in a poor, remote, rural community. It is certainly possible to introduce new technologies (laptops, tablets) into such learning environments in ways that are useful to her (and indeed: powerful!), but doing so is often, to borrow a phrase popular in Silicon Valley, non-trivial. Dysfunctional schools may be challenged to support the basic maintenance of ICT equipment. The regrettable (and often observed, around the world) phenomenon of computers sitting unopened in boxes, and of locked computer labs, is in my experience much more likely to be observed in schools in low income and/or challenging environments (especially where a school principal is not terribly strong). Does this mean that such places are not appropriate places in which to invest in ICTs? No, not necessarily. There are potentially 'pro-poor approaches' to utilizing educational technologies in schools, but, in my experience, they usually don't happen by chance (or by magic). Those best equipped to make use of the technology do so, best. Conversely, those least well equipped to take advantage of new technologies can in fact be negatively impacted by the introduction of new technologies.

(As a sort of side note or corollary, I'll mention parenthetically that those best placed to make use of ICTs are often the ones who actually get the devices and related content, training, connectivity and support. Indeed, investments to introduce new technologies into schools are often first made in places where success is most likely -- a topic I explored in last week's blog post when considering a different approach to scaling up educational technology initiatives.)

My point here is not to spark an argument about whether or not investments should be made in new technologies for schools, nor about which groups should (or should not) benefit from such investments. (Those can be and are useful arguments to have, but my goal is not to open up those particular cans of worms right now.) Rather, it is to suggest that the Matthew Effect in Educational Technology may well be relevant when new technologies are introduced into school settings in country X, or in community Y. Whether or not you think this sort of thing might be important, and/or what you might do as a result, is perhaps a matter of opinion (and eventually, potentially, policy). But before you begin whatever it is you plan to do, indeed while you are planning whatever it is you aim to do, it might be worth spending some time thinking about the potential for 'Matthew Effects' to occur, that what you are planning may largely result in further advantaging the already advantaged while not doing much to benefit those with a variety of disadvantages -- and plan/act accordingly.

It may in fact be the case that investments in new technologies are potentially even more important in poorly equipped schools, as tools to help overcome some of the many evident disadvantages observed in such environments. Compelling arguments can be -- and have been -- advanced in this regard in many places in the world. Unfortunately, however, the approach adopted by many well-meaning folks who 'win' such arguments and then move on to doing something as a result is too often what has been labelled the 'worst practice' in ICT use in education: Dump hardware in schools, expect magic to happen. The science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke once said that 'Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.' Sometimes, it must be said, magic does happen on its own. If you look selectively enough, you will no doubt be able to identify some magicians doing magical things with the computers (or tablets or mobile phones or interactive whiteboards or ___) that have found their way into their schools and communities despite the fact that little planning was done regarding how the devices would be used, and how this use could be supported. Some of these magicians may even be found in circumstances that might surprise you -- despite the fact that they had largely been left to their own devices. After 15 years of work with technologies in schools and communities around the world, rich and poor, urban and rural, with boys and girls and people of all different ethnic or tribal or religious affiliations, from China to India, Eritrea to Ghana, Cambodia to Costa Rica, I am not surprised when I come across such people and see the innovative and practical and sophisticated things they are able to do with ICTs. I continue to be energized and excited by these real life examples of what is possible, by the power of technology put to all sorts of inventive uses by creative students and teachers and principals in ways that are useful and relevant (and sometimes unexpected) to people's educations -- and to their lives. But I am also not surprised that these sorts of people, and the circumstances in which they operate, are often outliers. This isn't to say that other students and teachers and principals can't or won't be just as ingenious or inventive or creative with the same technology devices -- but they just may need a little (or a lot of) help and guidance and support along the way. "All things are possible": That's another quotation from the Book of Matthew. Too many planning efforts related to large scale investments in ICT use in education dwell too long on what is possible, while ignoring much of what is predictable, and in the end what is practical to do doesn't benefit the poor and disadvantaged all that much. But it doesn't have to be that way.

You may also be interested in:

- The Second Digital Divide

- A different approach to scaling up educational technology initiatives

- Educational technology and innovation at the edges

- A new wave of educational efforts across Africa exploring the use of ICTs

- One Mouse Per Child

- Interactive Radio Instruction : A Successful Permanent Pilot Project?

- Using ICTs in schools with no electricity

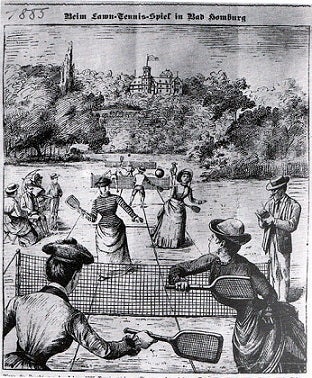

Note: The image of a tennis match in Bad Homburg, Germany ("advantage to the ladies at the top") comes via Wikimedia Commons and is in the public domain.

Join the Conversation