Photo credit: Amer Hasan

Recent studies in neuroscience and economics show that early childhood experiences have a profound impact on brain development and thus on outcomes throughout life. A growing number of impact evaluations from low- and middle-income countries underscore the importance of preschool for children’s development (to highlight a few: Cambodia, Mozambique, and Indonesia).

Most of these studies refer to the “high-quality” of their initiatives. But just what exactly do we mean by “high-quality”? How is quality measured in practice?

Such questions are frequently at the heart of debates between researchers and those engaged in policy discussions. Those of us who find ourselves involved in both conversations often struggle to find the balance between staying true to a (social) scientific literature and acknowledging the context in which our policy engagement happens.

We wrestled with these questions in a recent paper, where we investigate how preschool quality predicts children’s development outcomes ranging from their physical health and well-being to their language and cognitive development. We observed classrooms in 578 early childhood education centers catering to children aged three to six in rural Indonesia. To our knowledge, this is the largest such undertaking in the country to date.

Increasingly, researchers, practitioners, and policy makers alike recognize that pre-school quality is a combination of structural components (such as classroom materials, class size, teacher’s education and training) and classroom processes (such as children’s interaction with teachers, their engagement with learning materials or the range of activities they engage in).

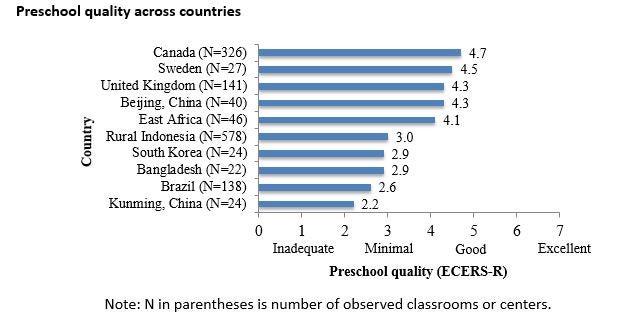

One of the most widely used instruments to measure preschool quality is the Early Childhood Environment Rating Scale (ECERS/ECERS-R) which provides a seven point rating from one (inadequate) to seven (excellent). Our review of the literature suggests that, on average, “high-quality” is difficult to achieve in settings as diverse as Canada and Bangladesh (see the chart below).

A closer look at the items in the ECERS-R reveals that the bar for an excellent service (or for that matter a good service), is set quite high. For example, one item focuses on the provision of TV, videos, or computers for classroom activities. Another item focuses on the provision of soft furnishings such as carpeted space and cushions for children’s relaxation and comfort.

In over three weeks of fieldwork in rural Indonesia, we rarely saw soft furnishings in preschools – sitting on the floor for children and teachers alike is a cultural norm. We encountered one center with a computer lab but this was a state-of-the-art location funded by three separate international donors.

To be clear, we are not suggesting that a high bar is undesirable. We believe that measures of preschool quality should take into account the realities of the local context where they are being applied. Just as the ratings used in the ECERS-R reflect the reality of the US context in which it was designed, we think it would be useful if internationally-standardized measures of preschool quality were calibrated to local standards when they exist.

In our paper, we do so using Indonesia’s local standards for preschool quality. Three findings emerged:

- The local standards include more than 50 percent of the ECERS-R items.

- The local standards employ very different scales than the ECERS-R; they employ a binary scale (i.e., Yes—meets standard/No—does not meet standard) compared to the seven-point scale used by ECERS-R.

- Whether or not the local standard is met corresponds to below what ECERS-R would categorize as minimal care.

Our paper not only calibrates internationally-standardized measures of quality with the local context but also addresses an important shortcoming in the literature relating to measurement error. We also examine how teacher characteristics (such as education and experience) and structural characteristics (such as student-to-staff- ratio and hours or operation per week) predict children’s developmental outcomes, given the considerable policy interest in these relationships.

So, what are the key take-aways from the study? We learned that:

- Using a subset of items from an internationally-standardized instrument that correspond with the local standards can provide researchers with a measure of classroom quality that better reflects the local context.

- Classroom observations of early childhood education quality are subject to considerable measurement error. Correcting for measurement error improves on the use of classroom observations as predictors of child development outcomes.

- The results are mixed on whether teachers’ levels of education and experience are significant predictors of child development outcomes.

- Attending longer hours of preschool is associated with better outcomes in social competence and language and cognitive development.

We hope that our study encourages collaboration among researchers and practitioners to think critically about how to measure and improve the quality of early childhood education in developing countries. If you have ideas or know of similar initiatives, please share in the comment section below.

For an overview of our paper and results, see here.

On April 14, 4:30 pm ET, tune in and join a high stakes discussion on how investing in ECD is one of the smartest things countries can do to end poverty.

Find out more about the World Bank Group’s work on education on Twitter and Flipboard.

Join the Conversation