The New York Times famously labeled 2012 the 'year of the MOOC', acknowledging the attention and excitement generated by a few high profile 'massive open online courses' which enrolled tens of thousands of students from all of the world to participate in offerings from a few elite universities in the United States.

What might 2014 bring for MOOCs, especially as might relate to situations and circumstances in so-called ‘developing countries’?

---

It may be hard for some in North America to believe, given the near saturation coverage in some English language web sites that focus on higher education and in certain thematically-linked corners of the English-language blogosphere, but the 'MOOC' phenomenon is only just now starting to register with many educational policymakers in middle and low income countries around the world. While many MOOCs have (from the start, and increasingly) attracted students from all over the world, at the policy level, 'MOOCs' have not – at least in my experience during the course of my work at the World Bank on education and technology issues -- been a topic much discussed by our counterparts in ministries of higher education and universities. Yes, one does see the occasional bullet point in a PowerPoint presentation towards the end of an institutional planning meeting, but my impression is that this can often be as much a reflection of the speaker’s desire to project a familiarity with emerging buzzwords as it is a reflection of any sustained strategic or practical consideration of the potential relevance (or threat) of MOOCs to traditional practices in higher education outside of ‘rich’ countries.

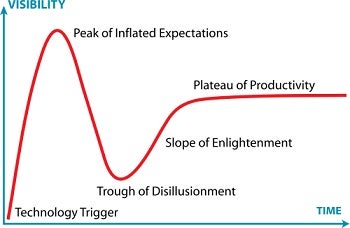

More than a few commenters in North America have invoked the Technology Hype Cycle (a concept developed and popularized by Gartner to represent the maturity, adoption and social application of certain technologies, and their application) when proclaiming that MOOCs have now past a 'peak of inflated expectations' to enter a period known as the 'trough of disillusionment' as a result of things like the recent change of course or ‘pivot’ of Udacity, one of the leading MOOC platform providers. While this assessment of the state of maturity/adoption may or may not be true from a North American perspective, and even if we concede that technology hype cycles are being compressed (it took Second Life and other ‘virtual worlds’, another recent notable educational technology phenomenon, three times as long to move from a period of great hype in educational circles to one of ‘disillusion’), such commenters may often neglect to consider that many hype cycles can exist simultaneously for the same technology or technology-enabled approach or service, depending on where you might find yourself in the world.

While this assessment of the state of maturity/adoption may or may not be true from a North American perspective, and even if we concede that technology hype cycles are being compressed (it took Second Life and other ‘virtual worlds’, another recent notable educational technology phenomenon, three times as long to move from a period of great hype in educational circles to one of ‘disillusion’), such commenters may often neglect to consider that many hype cycles can exist simultaneously for the same technology or technology-enabled approach or service, depending on where you might find yourself in the world.

While perhaps unsure of the extent to which MOOCs represent a 'threat' to existing educational practices, a new avenue for higher education, or perhaps something else entirely, I agree with people who say that the reports of the death of the MOOC are highly exaggerated. Roy Amara, the longtime president of the Institute for the Future, famously remarked that "We tend to overestimate the effect of a technology in the short run and underestimate the effect in the long run." I would not be surprised if this holds for many of the trends that we, as a matter of convenience, and correctly or not, group together under the general heading of ‘MOOCs’ today.

In my personal experience working at the World Bank on projects at the intersection of technology and education sectors, and when in discussions in many similar sorts of international organizations, ‘MOOCs’ are, generally speaking, still not a hot topic of consideration for educational policymakers in most middle and low income countries. That said, they are starting to gain increasing mindshare in some places. At the very least, they are generating some real confusion (and where there is confusion, there is potentially opportunity as well, for better and for worse).

As a result, many folks in the international donor community are now beginning to ask themselves questions like:

• How can, or should, we be talking about MOOCs when speaking with our counterparts in government around the world?

• What are the real, practical opportunities to consider in the short and medium term?

• Where, and how, might education ministries and universities wish to engage with related issues -- and what role (if any) should organizations like the World Bank play in this process of engagement?

---

For what it’s worth, and as a follow-up to a short series of MOOC-related posts on the EduTech blog earlier this year, I thought I’d share some of the things I am hearing in the course of my work at the World Bank related to this topic, in case doing so might in some small way enrich the global discussion around related emerging issues. What follows is based on my involvement in internal discussions (probably not really of much interest, but in case transparency in this area is useful, I draw on them here) as well as discussions with other international donor agencies, companies, educational institutions in developing countries, researchers, and with government officials. (Two groups notably absent from this list, at least in my estimation, are teachers and learners – for insights in those regards I have largely been relying on reporting by other groups.) As with all posts on the EduTech blog, the comments and observations here are my own – I don’t speak for my colleagues or for World Bank.

With that said, here are:

10 observations and comments about MOOCs and ‘developing’ countries

1. MOOCs and mindshare

While still a fringe or frontier issue in most educational policy circles in developing countries, preliminary discussions about the potential relevance of MOOCs are beginning in many places. Part of this is a result of the continued heavy press attention that this topic receives in media outlets in North America (here's a quite useful summary of this, from a government department in the UK). Part of this is a recognition, one supposes, that some of the best students (and faculty!) in some of the leading universities in a country have begun to explore MOOCs as learners. Some of these universities are also being approached as potential partners to extend the reach and offerings of existing MOOC providers. Articles with a focus on developing country contexts are slowly beginning to appear in the popular press, although this is admittedly mostly still occurring in press outlets in countries that are ‘exporting’ MOOCs. (Here at the World Bank we monitor press reports related to education issues in the counties where we work – which is most countries – and we don’t yet see many articles about MOOCs that are more than summaries of related stories that appear in Western news outlets.) Announcements such as those of the full computer science master’s degree program offered by Georgia Tech via MOOCs at a reduced cost have spread quickly within computer science faculties in developing countries, and academic leaders have begun to consider what these developments might portend for their universities.

---

2. MOOCs providers outside the United States

Until recently, the fact that the three largest and most prominent MOOC platform providers (Coursera, EdX, Udacity) are based in the United States has meant that MOOCs have been largely considered by many to be an American* phenomenon. This is starting to change as MOOC providers and initiatives of various flavors emerge out of countries like the UK (FutureLearn https://www.futurelearn.com/), Germany (iVersity), Spain (UniMOOC) and Australia (Open2Study), as well as from developing countries such as Brazil (Veduca) and China (XuetangX and Ewant). Kepler from GenerationRwanda is a Rwanda-based MOOC. Ireland-based ALISON is actually considered by some to be the first MOOC provider (predating the ‘big three’ American initiatives).

The large American MOOC platform providers currently reach students all around the world and are exploring potential link-ups with some of the leading higher education institutions in countries such as China, Brazil and Turkey. Initiatives such as Coursera’s Learning Hubs, physical spaces supported by partners where MOOC participants can gather, suggest a potential model to extend the reach of MOOCs to groups of learners in developing countries who may not be already accessing, or completing, MOOCs.

With the emergence of what essentially are ‘national champion MOOCs’ in many OECD countries, I would not be too surprised to see a few international donor agencies support the expansion of such efforts as part of their developmental assistance program.

*Apologies to my hemispheric neighbors for using the term 'America' here to refer only to the United States, a formulation against which I know many other inhabitants of the Americas chafe. Special apologies in this regard to one group of North Americans: those in Canada, where many of the leading theorists and early pioneering practitioners in the MOOC field continue to be found.

---

3. Research about MOOCS

Precious few of the policy decisions made to date related to MOOCs have been evidence-based. This isn’t meant as a criticism, necessarily, but rather to reflect the reality that large scale MOOCs have not been around for a terribly long time, and so there is a very shallow research base to inform related policymaking, no matter the country. This is starting to change.

Two aspects of MOOCs make them particularly interesting for researchers: the fact that some of them have so many students (thousands, and in some cases tens of thousands), and the fact that, because every aspect of participation in a MOOC (each click, each pause of a video, each forum post, each log-in, each test answer) generates data -- indeed, *lots* of data! A recent paper from researchers at the University of Pennsylvania, one of the first institutions to offer MOOCs, looks at Who Takes Massive Open Online Courses and Why?. Expect to see many more such research papers emerge in the coming months, especially as a result of the Gates Foundation-funded MOOC Research Initiative, which last week brought researchers to the University of Texas at Arlington to report on their progress with 30 research projects. While most of the MRI-funded research has a decidedly ‘developed country’ flavor, much should have broader relevance as well. Preliminary results and lessons from the Georgia Tech computer science degree MOOC, which in part explicitly targets students in Africa, as well as from the World Bank pilot in Tanzania, should also begin to emerge by the middle of next year.

---

4. MOOCS vs. online learning vs. distance education

When asked to participate in strategic discussions about MOOCs, I often quickly find myself asking: What are we really talking about here? I am not talking about the differences between so-called ‘cMOOCs’ and ‘xMOOCs’ (for better or worse, a distinction that has greater currency among certain sets of academics than it does for most education policymakers). I am talking about misunderstandings that are more fundamental.

Many times when I am asked to advise groups considering MOOCs, I find that they conflate and confuse a number of different things, and what these groups really want to talk about is some form of distance education or online learning offering. As a practical matter, it usually isn’t too difficult to identify a policymaker’s real information needs in this regard, once a few core definitions are made and common agreement is found for the use of a few common labels. While many initial inquiries from policymakers in developing countries (and their interlocutors in donor agencies) that arrive in my in-box may at first glance appear to be about ‘MOOCs’, I more often than not find that lots of experiences, models and lessons in online learning and distance education from places like the University of South Africa (UNISA), Indira Gandhi National Open University (India) and Malaysia’s Wawasan University (to cite just three of many prominent institutions with a long track record of providing distance learning to students in developing countries) are really the relevant ones to pass along, together with references to 30+ years of longstanding practices of potential relevance. The World Bank’s specific experience supporting the African Virtual University is often seen to be of value as well.

---

5. Criticisms of MOOCs in developing countries

Type in ‘MOOC’ to your favorite search engine and you will quickly see that there is no shortage of opinions on the ‘MOOC phenomenon’, positive and negative. One legitimate response to criticisms of MOOCs is that this stuff is all quite new, and so certain criticisms may be premature, as everything is changing so quickly. Even if you sympathize with such a line of thought, just because MOOCs are in their infancy doesn’t mean that *all* criticism is unwarranted. There is some rather predictable crankiness from certain segments of the established professoriate and commentariat which, even if it is at times a bit unfair, perhaps serves as a useful antidote to the rather breathless enthusiasm of some evangelical technologists who have, on a basis of a few quite fascinating and quite innovative initial activities, proclaimed that a revolution in higher education is at hand. (There are of course lots of views in between, and even a few outside, these two extremes.)

In a previous blog post from a few months ago, I tried to quickly summarize some of these criticisms:

Some critics may lament that MOOCs represent a return to the 'sage on the stage' mentality that ICT-enabled learning practices were meant to make obsolete.

Other critics may see in MOOCs yet another wave in cultural imperialism from the 'North' and the 'West' crashing across borders, washing over (or possibly washing out) local educational institutions, cultural norms and educational traditions.

Still other critics fear the institution of a markedly two-tier system of global higher education, with a small number of elites able to participate in education the 'old-fashioned way' in small, intimate, face-to-face groups in close physical contact with their professors, while the vast majority of students, especially those in developing countries, have to make do with participating in a watered down, inferior educational experience delivered through MOOCs.

For what it’s worth, here are some of the most common criticisms of ‘MOOCs and developing countries’ that I am hearing these days from counterparts who work with technology in education in developing countries:

Readiness for MOOCs. In many developing countries, there is simply inadequate technology infrastructure to support the systematic use of MOOCs in any substantial way. This is true. This criticism is quite easy to understand – and agree with. That said, it is also true that we have seen explosive growth in the availability and affordability of ICTs over the past dozen years or so in many developing countries. Things can thus change quickly in this regard – not quickly enough, perhaps, especially for large segments of a country’s population (see also next item below), but, from an historical perspective, pretty quickly indeed. Even where the technology infrastructure is in place and affordable, to date most of the courses have been offered in English. While this is changing, it still represents a rather significant barrier to participation in MOOCs by the majority of learners.

MOOCs and equity concerns. Another of the most obvious -- and legitimate, in my opinion -- criticisms of MOOCs relates to equity. As a recent paper from University of Pennsylvania researchers finds, most people who successfully complete MOOCs already have a university degree. SciDev.Net has summarized these findings as “Massive open online courses appear to reinforce the advantages of the elite”. In other words, despite much rhetoric (and a number of inspirational anecdotes about poor people in poor places benefiting from participation in MOOCs), a Matthew Effect seems to be in evidence here. In many ways, this shouldn’t be all that surprising. The first mobile phones I ever saw were toted around by rich people on golf courses in North America. Now, 30 years later, mobile phones are celebrated as one of the truly democratic technologies around, with the devices increasingly in evidence in some of the poorest communities in the world. Just because a technology benefits a privileged group today doesn’t necessarily mean that this will always be the case. But it doesn’t mean that it won’t be the case either. Those touting MOOCs as a way to provide access to education for some of the poorest and most disadvantaged groups in developing countries don’t yet have much evidence to back up such claims.

MOOCs and ‘cultural imperialism’. Criticisms of educational ‘exports’ from countries in the more ‘developed’ Global North and West to ‘less developed’ counties of the Global South often are met in some quarters with charges that they are a form of cultural imperialism. Criticisms of this sort are often understandable, and predictable. As someone who both carries an American passport and works at the World Bank, I suspect comments from me on this issue may carry a sizable discount factor for many, so I'll try to refrain from much editorial comment here. One response to such criticism that I hear is that many of the most popular MOOC courses are quite technical (e.g. courses in gamification and big data), and there is, I am told, often less cultural ‘baggage’ attached to MOOCs in these areas than there are to, say, course in the applied social sciences and arts. As transnational MOOCs emerge from the ‘South’ and ‘East’ as well, I suspect that some criticisms in this regard may become more complicated and nuanced.

MOOCs and the building of ‘local capacity’. When I speak with education policymakers in developing countries about MOOCs, I often find that many of them have never heard of the word or concept. Those that do know about them, though, quite often recite back to me some version of the prediction/boast of Udacity founder Sebastian Thrun that, as a result of MOOCs, "by 2060 there will only be 10 universities in the world". In my experience, this quotation is not repeated very warmly or fondly by such folks. Indeed, it is understandably considered a threat (and a rather hubristic one at that) and often serves as a barrier of sorts to exploring informed discussions about the potential relevance (or lack of relevance) of MOOCs to specific educational contexts. If we partner with [insert name of MOOC platform provider here], how will we ever develop the capacity to do this sort of thing ourselves? Even where we acknowledge that many of our university lecturers may not be of the highest caliber today, are we meant to throw in the towel and essentially outsource the teaching of courses to more highly qualified teachers in other countries? How will this help us improve the quality of our own faculty members going forward? If we are merely adopting technologies developed and maintained by others, how we will we develop the capacity to develop such technologies ourselves? If one of the core competencies of universities in the future relates to their ability to offer courses online, how are we to develop as an institution if we effectively outsource this competency to another group? These are all legitimate questions to ask. I won’t attempt to discuss potential answers to them here, but I will note that there are basically two ways for policymakers to view opportunities to utilize MOOCs: They can essentially (and passively) participate in the ‘MOOC phenomenon’ as a consumer of things produced elsewhere, or they can use participation in MOOCs as a strategic opportunity to help develop related local capacities. Both options are legitimate, but the latter option, while much more difficult to pursue, may be worth serious consideration.

MOOCs as vanity projects. A number of countries have decided, as a developmental priority, to support the creation of a small number of ‘world class universities.’ My former World Bank colleague Jamil Salmi has highlighted the danger when governments and universities concentrate too much of their efforts to this end, neglecting other important constituent components of a healthy tertiary education system. One worst-case result can be the creation and cultivation of what are essentially ‘vanity projects’. In some circumstances, the decision to create a MOOC instead of investing scarce resources in other areas may yield a similar sort of result.

These are just a few of the common criticisms I hear of MOOCs and developing countries; there are of course many more, potentially. For what it’s worth, one criticism that I hear rather loudly among critics in developed countries about MOOCs relates to commenters’ lack of comfort with, if not outright opposition to, the role of ‘private capital’ in education. I note this here not to rehash or examine related criticisms – you can find plenty such discussions on the Internet without too much difficulty – but only to say that, in my experience, this reflects a certain strain of discourse that predominates mostly in 'developed' countries. At least so far: Perhaps, as certain MOOC providers become a more established part of the landscape in various places, such criticisms may emerge with greater volume from commenters in developing countries as well.

It is also perhaps worth noting (and this is perhaps stating the obvious) that one typically encounters multiple perspectives on MOOCs within a single higher education system. Some universities may see them as ‘competition’, for example, while some ministries of higher education may see them as an opportunity (or vice versa).

---

6. Getting started with MOOCs

A quite common question that I hear from education officials in developing countries is: What level of ICT infrastructure is necessary to participate in MOOCs? Or, as it was once rather memorably phrased to me: What is the ‘minimally viable reality’ [interesting phrase!] we need to make this sort of thing happen?

On the learner side, this is usually a pretty easy question to answer: You need regular access to a computer with reliable and affordable broadband Internet connectivity. (You also, it should be noted, usually need a good command of English, the dominant language of MOOCs to date, and you always need a lot of discipline.)

At the level of an institution, answers to this simple question become much more complicated. Where an institution is looking to support students participating in a MOOC offered by an existing MOOC provider, dedicated facilities and pedagogical support mechanisms (of the sort being explored under the Coursera Learning Hubs initiative) may be required. If an institution itself wants to beginning offering a MOOC or two, partnering with an existing MOOC provider presents probably the easiest course of action. Where an institution would like to grant credit for its students to participate in a MOOC offered by another institution, it may need to put into place new mechanisms, guidelines and practices if such things are not covered by existing accreditation bodies or schemes.

Where an institution (or a consortium of institutions) in a developing country wishes to set itself up as a MOOC provider platform, things are *much* more complicated, time-consuming, and expensive. World Bank experiences supporting initiatives such as the African Virtual University have shown that there are no shortcuts to developing and cultivating the administrative, pedagogical, financial, and technical capacities and infrastructure necessary for institutions to successfully offer online distance learning of various sorts. Even where such capacities and infrastructure can be developed within institutions, local technology ecosystems (e.g. sufficient competitive providers of reasonably-priced supporting goods and services) need to be in place to support both institutions and learners as well.

---

7. MOOC technologies vs. MOOC platform providers

For a number of countries (or institutions within those countries), partnering with an established MOOC provider platform may not be of current interest, for a variety of reasons, including those related to things like national interests, institutional capacity and/or specific local contexts. Even where such cross-national partnerships may not be desired or possible in the short term, the specific technologies that power many of the established MOOCs may well be of interest and relevance. The technology tools to do this stuff will get cheaper and more powerful – and be more widely diffused. Already some very useful software tools have been made available as open source – good news for places not only trying to provide additional avenues for students to participate in higher education, but also trying to develop local technical capacity to develop, support, maintain and (through advanced data analytics tools) learn from MOOCs. There is no denying that many technical barriers (e.g. lack of reliable, affordable broadband connectivity) and other challenges (e.g. Matthew Effects) will continue to restrict the potential relevance of MOOCs to certain populations in developing countries. That said, it is also safe to predict that, over time, more people will be able to access and benefit from online learning offerings (including MOOCS) in such places, both because they will be increasingly connected (as a result of greater availability of broadband and devices that are both more powerful and cheaper), and because there is are cohorts of more educated people emerging around the world as a result of progress made under the education for all movement of the last 20 or so years.

Side note: About 15 years ago I worked on a program that sought to connect students and teachers in 22 developing countries to the Internet, and each other, as part of collaborative learning activities. Some of the rationales for making such connections were based on the assumption that (e.g.) students in Uganda might want to connect to students in California. Such connections were made, and were seen to be of value to students and teachers in classrooms in ‘developed’ and ‘developing’ countries alike. Often of greater, and more sustainable, value were connections between teachers and students within a country itself, facilitated and enabled by the access to technology tools developed in large part in places like (e.g.) California. I wonder if there might be some lessons from this experience of potential relevance to some of the emerging MOOC providers …

---

8. MOOCs and mobile devices (like mobile phones)

If MOOCs are to be able to reach large numbers of learners in developing countries, they will need to be accessible on the connected ICT devices that these learners have available to them. In most of the world, this means things making MOOCs fully accessible via things like mobile phones. Whether and how this can/will be done may be key to the realization of ambitions of many MOOC providers in the coming years.

Side note: I wrote a post on the EduTech blog back in the summer about '10 principles to consider when introducing ICTs into remote, low-income educational environments', which was adapted for re-publication in the Globe & Mail. In the original post, I said nothing (at all!) about MOOCs. While I was delighted to have something I had written appear in one of Canada's most important news outlets, I was a little surprised to see it carry the headline ''MOOCs don't help developing countries -- phones do”. As I noted in a comment on the Globe & Mail site, there isn't an either/or choice here: There is sufficient room for lots of innovations to be introduced and tested to help meet wide varieties of needs of learners around the world. While we should be skeptical of the attendant hype around any new technological innovation to benefit educational practices and opportunities, we shouldn’t let this skepticism blind us in cases where there is real value and opportunity. MOOCs, mobile phones (to say nothing of MOOCs on mobile phones ...) -- we are still in the early days of experimentation here.

---

9. The evolution of MOOCs

MOOCs are emblematic of some of the technology-enabled changes that are challenging ‘business as usual’ in some places, but perhaps don’t (yet) themselves challenge much of the usual business of education. Whether or not this changes, more people will be able to access MOOCs in the future: because there will be more of them, because connectivity will continue to improve and because there are emerging cohorts of educated people emerging around the world as a result of progress made under the education for all movement of the last 20 or so years.

One thing is clear: As relates to the practice and potential of MOOCs within education systems in middle and low income countries, we are still in the very early days. These things will change and evolve -- perhaps quite radically, in some cases. No matter how one feels about ‘MOOCs 1.0’, one expects that rapid iteration and evolution and learning (and ‘pivots’) are to be expected in the near future. While MOOCs as they exist today may not speak to the needs of many learners and institutions in developing countries, the next iteration (MOOCs 2.0?) may well evolve in response to contexts and realities and innovations in such places. (By the time MOOCs 3.0 roll around, let’s hope we have come up with another names for these things – or at least a more pleasing acronym!)

The Canadian ice hockey great Wayne Gretzky used to attribute some of his success to the fact that he would skate to where the puck is going to be, not where it has been. Given the pace at which MOOCs (and other technology-enabled innovations in education) are evolving, educational policymakers considering their relevance and utility in helping to meet their country’s and institution’s education goals might do well to (metaphorically) do the same.

---

10. _____

There is more I could say here, but I'll stop now, as I’ve already gone on much too long. The list here is meant to catalog some of the things that I am hearing discussed at the end of 2013 related to the relevance of MOOCs in developing countries. It is certainly not comprehensive, and is presented in no order of importance. (I fully concede that what is *not* discussed can often times be just as interesting, and illuminating, and important.) Are these the most important issues and concerns that people *should* be talking about right now? In many cases, I suspect perhaps they are not, but my hope here is to share some of the reality that I am seeing and hearing—not what I think or hope this reality might or should be.

As one small acknowledgement of my limitations when discussing this (quickly changing) topic, I have (as with other lists of ten that appear from time to time on the EduTech blog) deliberately left #10 blank here. Please feel free to add your own observations below.

You may also be interested in the following posts from the EduTech blog:

• MOOCs in Africa

• Making Sense of MOOCs -- A Reading List

• Missing Perspectives on MOOCs -- Views from developing countries

• Debating MOOCs

• 10 principles to consider when introducing ICTs into remote, low-income educational environments

• The Matthew Effect in Educational Technology

Note: The picture used at the top of this blog (“an award-winning mooc(ow), as Joyce might say”), is in the public domain and comes from Wikimedia Commons. The graphic of the Gartner Hype Cycle comes from Wikipedian Jeremy Kemp via Wikimedia Commons and is used according to the terms of its Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. To learn more about the Gartner's trademarked Hype Cycle methodology, please see the related page on the Gartner web site.

Join the Conversation