Large declines in reading scores are recorded by Indonesia and Thailand.

Large declines in reading scores are recorded by Indonesia and Thailand.

In the early morning hours of December 3, the OECD’s PISA 2018 results came pouring in. A record number of 79 countries participated, with the East Asian powerhouses topping the lists. But the headlines lamented the lack of progress, especially in high-income countries.

In most of the middle-income countries, predominantly from Latin America, Eastern Europe and the Middle East, the word “stagnation” was the more common.

But there was some rejoicing in the superior performance of several countries, namely Estonia, Ireland and Sweden.

First time participants in PISA such as Belarus and Ukraine did relatively well, but certainly not all - for example, the Philippines.

While headlines focus on rankings, we ought to look beyond them, especially since we have several rounds of PISA data for some countries. For example, Turkey has been participating since 2003 and one of the headlines that was quite misleading was “Turkey Falls Behind OECD Average in PISA 2018.” While it is true that Turkey’s score is below the OECD average, the country showed the highest increase in mathematics and science performances between 2015 and 2018, putting them back on track to improve and catch up to the OECD average. Similarly, Ukraine’s performance is presented as lagging when in fact Ukraine is a positive outlier – that is, given its level of development, Ukraine is performing above expectations. They are building a sound foundation and should continue to implement the ongoing reforms and see improvements.

Beyond the rankings

While high-income and OECD countries may not be showing much progress, there have been changes worth exploring further. Given the PISA 2018 focus, our report is on reading.

In terms of rankings, the top 10 was dominated by East Asian economies, with China (represented by only 4 provinces), Singapore, Macau (China), and Hong Kong (China) in the first 4 positions, while Korea was 9th. In positions 5 to 8 were Estonia, Canada, Finland and Ireland in that order. Poland was 10th (and Sweden 11th) – both representing significant improvements over time. What is interesting is that this is the same top 10 as in the previous PISA 2015 rankings, except for the additions of the four Chinese provinces, Macau (China) and Poland. Dropping out of the top 10 are: Belgium, Japan and Norway.

However, the biggest gains between 2015 and 2018 were recorded by primarily a handful non-OECD and middle-income countries.

Among the biggest improvers was Macedonia with an advance of 41 points – which represents more than a whole year of learning gain. Turkey showed a gain of 38 points, also about a year’s increase. Jordan had an 11-point gain. Macau (China) achieved an increase of 16 points.

Small gains were made by many other countries. Among middle-income countries, these were Brazil, Kosovo, Lebanon, Moldova, Peru and Qatar. And many middle-income countries saw no significant changes or some declines.

Among the largest declines between 2015 and 2018 were in Indonesia, with a 26-point decline (although in the context of impressive increases in enrollment); Georgia, 21 points; Cyprus, 19 points; Netherlands,18 points; Dominican Republic, 16 points; Russia, 16 points; and Thailand, 16 points.

Performance over the Longer Term

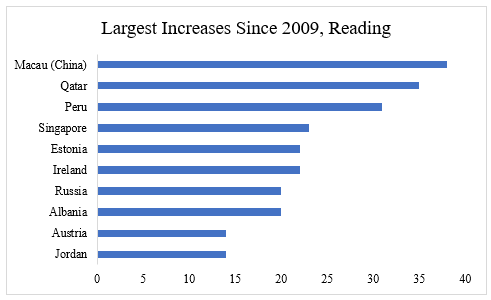

Going back further is instructive. Since 2009, the largest increase in reading scores was recorded by Macau (China). Among “developing” countries, Peru improved by 31 points, Albania by 20 points, and Jordan by 14 points.

Other countries, however, are not faring so well. Large declines in reading scores are recorded by Indonesia and Thailand. The declines in scores are equivalent to about a year of learning. Indonesia’s challenge has been to improve quality while also expanding access. The PISA report does show that when the sharp increases in enrollment are considered, Indonesia has been successful in absorbing a large mass of new students without compromising quality. But the overall level of this larger student population is still below what it should be given Indonesia’s level of development.

Since reading was the focus in 2000 as well, it is interesting to see that Peru has the largest increase over time, followed by Albania and Chile. In terms of declines, Thailand and Indonesia lead, but it is worth noting the significant declines among leading rich countries such as Finland and Japan.

Over time performance in reading is clearly not determined by income alone. There is no convergence, in the sense of poorer countries massively catching up. The most consistently improving middle-income countries since the start of the millennium include Albania, Brazil, Chile and Peru; but many others have a lackluster performance. Nor there is evidence of divergence of only rich countries improving. Rich countries are showing very different long-term trends.

Progress is happening, but not enough, and too slow

We see that change is possible and countries’ investments in education and implementation of policy can have a positive impact. Countries such as Brazil, Mexico, Turkey and Uruguay have seen impressive gains in enrollments in secondary education, without sacrificing quality. That gives hope that more young people will have an educational experience that will give them an opportunity in life.

Education today is not about teaching students the content and information but about ensuring that all students learn. It is about giving all students the skills to thrive in an increasingly uncertain world. To a minimum all should be able to understand a text, decode and criticize, distinguish facts from opinion, and question what they read. That is happening, but the levels and trends in middle-income countries are very heterogenous.

While there are countries making gains in quality, they are still insufficient, and these countries are far from where they should be. To give an example, in Indonesia, only 30 percent of 15-year-olds are at the minimum proficiency level in reading expected at that age. In Brazil, only 50 percent of 15-year-olds have the expected reading and understanding skills. Albania, Jordan and Peru, despite being the countries with the highest growth, have over 50 percent of young students who do not pass the minimum standard for reading. Brazil is an interesting case, because it has achieved impressive gains in learning in primary education, but less notable in secondary. Progress is uneven – and investments in young people have to continue relentlessly.

One element that is likely to be a determinant of success is early reading. That is the why the World Bank has adopted a reading target based on a new “Learning Poverty” indicator – which is the share of 10-year-olds unable to read and understand what they read. The target is meant to help set the foundation for learning in the schooling years of each student around the world. This, we believe, will help set them for success in schooling – and life. With a focus on reducing learning poverty levels in each country, along with consistent and appropriate investments in the education system, it will be easier to see increasing secondary school scores in the near future.

Join the Conversation