This week the IFC – the World Bank Group’s private sector arm – holds its 6th International Private Education Conference. The occasion prompted us to think about what it would take for the private sector to scale up and really make a difference to children’s lives across the globe.

We’ve all heard the figures of 57 million out-of-school children and 250 million children who cannot read. But the extent to which the private sector can play a role in addressing these challenges depends on answers to the following questions:

- Are there enough successful models out there to bridge the gap?

- How quickly can these models expand, but still maintain the same level of quality?

- Is the regulatory environment conducive for ensuring that these models are held accountable and given the freedom to innovate?

1. Pioneering models exist in developing countries.

In Africa, Bridge International Academies and Omega Schools are two rapidly expanding private, independent school chains. Bridge in Kenya was founded in 2009 and currently operates 134 schools, educating 50,000 students. The chain plans to expand outside Kenya to reach more than 100,000 students in coming years. Bridge’s “school in a box” concept supports this rapid expansion.

Omega, currently operating in Ghana and Sierra Leone, was also founded in 2009. It currently operates 38 schools, which are currently educating 20,000 students, and hopes to double in size in the next year. Part of Omega’s appeal is that it collects student fees daily to make school more accessible to lower income families. Tuition at these schools is, on average, a few dollars a month, with many poor households willing to pay the fees.

Outside of Africa, other low-cost chains are being formed, including IDEO’s 23 Innova schools in Peru, currently educating 13,000 students, and APEC in the Philippines, which currently has one pilot school with plans to expand to 12 schools this year.

The lack of any rigorous impact evaluation for these chains remains a concern. To remedy this, the World Bank is seeking to increase the evidence base for low-cost, private schools through its Strategic Impact Evaluation Fund. For example, in Mexico, a school targeting the poorest of the poor, run by the nongovernmental organization Christel House with more than 2600 students enrolled, is being evaluated by the Bank and Mexican researchers.

2. Lessons for scale have been demonstrated in England and the United States.

In some countries, expansion of private school chains has been supported by government funding rather than fee-paying parents. In England, 55% of all secondary schools are state-funded, independent academies. ARK, recognized as one of the country’s top performing chains, was founded in 2006 and currently operates 27 schools. ARK also aims to educate 20,000 secondary school children at state-funded ARK-supported schools in Uganda.

In the United States, 6% of public schools are charters. Uncommon Schools operate 38 charter schools in the northeast region. The chain recently won the Broad Prize for Urban Education in recognition of students’ high performance. Meanwhile, KIPP, the largest charter school model, operates 141 schools, educates 50,000 students, and is currently celebrating its 20th anniversary. KIPP is one of the few models that have been evaluated using rigorous impact evaluation, and is now expanding to developing countries through its One World school network in Mexico, India and South Africa.

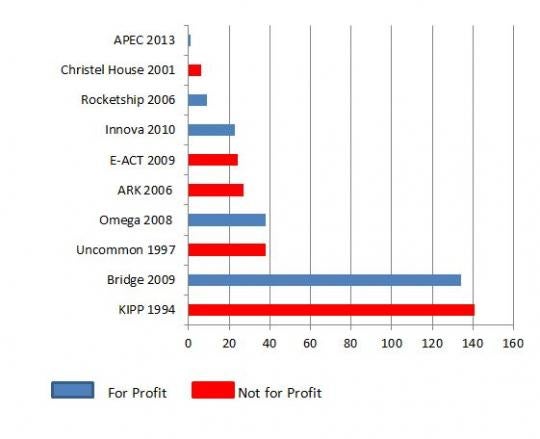

Comparisons of selected private-funded and government-funded non-state chains

Number of Schools and Year Established

Source: Organization websites

3. A strong regulatory environment can help to ensure quality

We offer a few cautionary tales on ensuring quality: Education Week recently reported that some school leaders at Rocketship, a U.S. charter school chain that uses “blended learning,” had concerns over the expansion of the model before its impact had been rigorously studied. Leaders are now reviewing the model but still plan to open another 50 schools in the next five years. The role of legislators will be to ensure that standards are improved in existing schools, and applications for new schools are also scrutinized.

E-ACT, one of the largest chains in England, recently lost the right to operate 10 academies—one-third of its schools – due to poor inspection results. Once again, this highlights the stewardship role of the state in ensuring high-quality schooling for all.

What do these examples teach us about what is needed to ensure high-quality scalability?

Create the right model and test it through rigorous evaluations:

We know a lot about successful charters and academies thanks to research by Abdulkadiroglu, Dobbie and Fryer, and Tuttle, among others. An evaluation of 43 KIPP middle schools found that students were about 11 months more advanced in learning than students who did not attend a KIPP school. But we need to learn more about what works in developing countries for the poor.

Ensure that expansion replicates the fidelity of the model and is financially sustainable:

Proven, strong instructional models that deliver high-quality student outcomes must be supported by efficient, technology-enabled, back-office functions and strong financial management. This enables financial viability, allowing schools to scale up. A report by the Center of Education Reform found that 41% of charter school closures in the U.S. were due to financial difficulties.

Establish the right regulatory environment , which supports the following:

a. Encourages innovation among providers. The government allows private schools to decide on teachers, curriculum and learning materials to meet the needs of the local community.

b. Holds schools accountable for results. In the interest of accountability, the government monitors schools through inspections and standardized tests, and intervenes as appropriate.

c. Empowers parents, students and communities. The government provides information on school performance, sometimes in form of school report cards, so parents are able to choose based on quality.

d. Promotes diversity of supply. The government ensures new, non-state schools are able to enter the market to support new models and reduce monopolies.

In sum, the private sector can scale up and make a difference for 57 million children out of school and the 250 million who cannot read. It will take rigorously validated service delivery models and financially sustainable expansion. The public sector can play its part by establishing a regulatory environment that supports innovation, ensures accountability, empowers parents, and promotes diversity of supply.

Follow the World Bank education team on Twitter: @WBG_Education

Join the Conversation