While radical approaches are needed – given the desperate state of most public education systems; just see the poor results of most middle income countries in international assessments such as PISA and TIMSS – there are more mundane approaches, already in practice, that could be made to offer so much more. Giving public schools adequate resources, the right to make appropriate decisions, and holding them accountable through the publication of school results – in short, school autonomy – has been used in countries around the world since the mid-1960s. The school autonomy approach – be it known as school-based management, whole school development, comprehensive school reform, or parental and community participation – has been tried, evaluated, and proven successful at achieving a range of education goals in many different contexts.

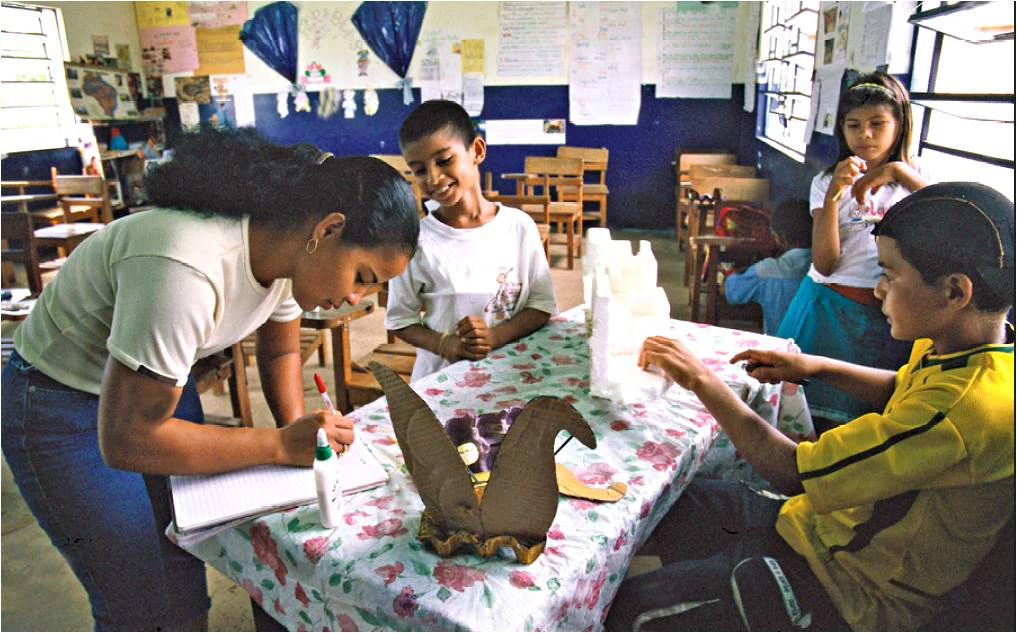

In the developing world, the approach was first experimented with in the early 1990s in El Salvador, evaluated by among others Emmanuel Jimenez and Yasuyuki Sawada, and has been copied in a number of countries, including Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua. The school-based management approach tries to empower schools by allowing them to make more of the key decisions. In El Salvador’s EDUCO model, for instance, school councils comprised of parents and other local stakeholders can hire and dismiss teachers. Evaluations show that such schools increase parental participation, increase efficiency – by raising resources, reducing repetition and dropout, and may increase learning outcomes as measured by standardized tests. Moreover, such results are achieved very cost-effectively, meaning that public spending on such schools is equal to or less than what is typically spent on traditional public schools.

Such results are not limited to low and middle income countries either. School-based management started in Australia in the 1960s, spreading to the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom -- in fact, more than 60 countries have some form of school-based management. One of the most careful and long-term studies of the impact of school accountability was published last year in the Journal of Political Economy by Damon Clark. He found that the British reform that allowed public high schools to opt out of local authority control and become autonomous schools funded directly by the central government, led to large achievement gains at schools benefiting from the reform.

Bulgaria decentralized its school system giving principals the power to hire and fire, control budgets, in short make all the important decisions at the school level. This strong version of school autonomy is being expanded with additional accountability measures, namely the use of assessment results and increased participation by parents on the school council.

Mexico, through more limited school autonomy programs, has been able to improve schooling outcomes for students in the poorest and most indigenous schools in the country. There are many other countries one could list. In fact, at the Word Bank alone, more than 20 school autonomy or school-based management programs are being assessed through a randomized or otherwise rigorous evaluation design.

So, it’s with some disappointment that we receive the news of the abandonment of the school autonomy models in the Central American countries that pioneered the approach in the developing world.

Join the Conversation