As 2020 comes to a close, the COVID-19 pandemic continues to ravage education systems around the world, keeping hundreds of millions of children out of school. While the recent news about successful vaccine trials is promising and signals a light at the end of the tunnel, the harsh reality is that millions of youth who lost access to schooling during the lockdowns may never return. Those who do return will have suffered significant learning losses. The World Bank estimates that learning poverty could increase from 53% to 63% globally, which implies that 72 million additional children could fall into the ranks of the learning poor. That will have repercussions for decades to come. Without effective policy responses when schools reopen, approximately $10 trillion of lifecycle earnings could be lost for this cohort of learners —because of lower levels of learning, lost months due to school closures, or greater potential for dropping out of school.

Given these scenarios, the newly released results from the OECD’s PISA for Development (PISA-D) survey of out-of-school youth are particularly relevant and thought-provoking. The survey, which took place in 2018, measured the knowledge of 14- to 16-year-old out-of-school youth in five countries – Guatemala, Honduras, Panama, Paraguay, and Senegal. This was in addition to an earlier (2017) in-school assessment of 15-year-olds in these countries. The results from the out-of-school survey, which were released on December 1, together with results from the earlier in-school assessment, clearly show the learning crisis that existed in these countries even before COVID. The results are a message to education systems around the world of the cost of failing to educate youth with the basic competencies needed to survive in today’s world and of allowing them to drop out of school early.

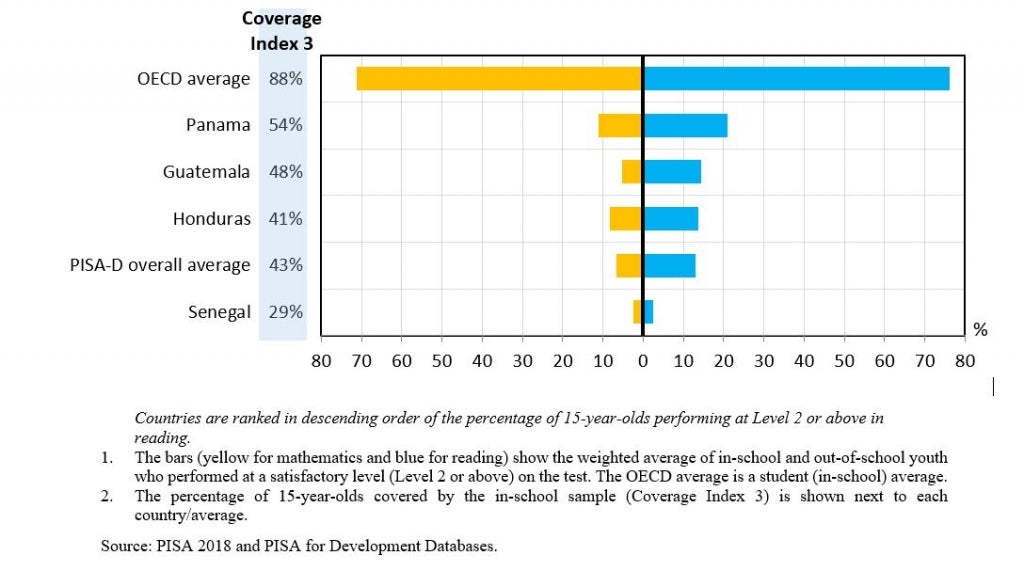

The PISA-D results reveal that while more children than ever may be going to school in the participating countries, too many leave before completing the primary cycle (in fact, according to Figure 1, only 43% of the 15-year-olds in these countries – about half the OECD average – were enrolled in at least grade 7 and therefore eligible to sit the school-based tests). Many more fail to achieve even minimum levels of proficiency in reading and mathematics. For example, the proportion of 15-year-olds in these countries achieving at least minimum proficiency in reading is less than 15% while in mathematics, it is less than 10% (compared to an average of 76% and 71% respectively in OECD countries). This is despite almost half of these youth having attended school for up to nine years.

Figure 1: Performance in reading and mathematics amongst in-school and out-of-school youth

Percentage of 15-year-olds performing at Level 2 or above1

The education challenges facing the PISA-D participating countries

The PISA-D participating countries should be acknowledged for the progress they have made in ensuring wider access to schooling, but they still have a long way to go to ensure that every child completes at least nine years of basic education and acquires at least basic skills in reading and mathematics (a principal aim of Sustainable Development Goal 4). While it is rare for a child never to enroll in the participating countries, more than half of the children in these contexts, boys and girls, drop out of school before they reach the secondary level. Almost all of the children that drop out have previously repeated grades and have not acquired even minimum levels of proficiency in reading and mathematics by the time they leave.

Crucially, when it comes to school-based factors, it is the quality of instruction, particularly the teaching and learning of reading skills in the early grades of primary education, that is the key to successful academic outcomes at age 15. The levels of reading ability of students at the ages of seven or eight are the strongest predictors of whether a child will achieve at least minimum levels of proficiency in basic skills by the age of fifteen. Being able to read is also a strong predictor of whether students will stay in school.

Currently, however, more than 70% of the children in PISA-D participating countries who go on to complete lower secondary education are unable to achieve even minimum levels of proficiency in reading and mathematics, and practically none of the children in these countries who fail to complete lower secondary education have achieved minimum levels of proficiency in reading or mathematics.

What can be done about it?

Improving learning levels for in-school and out-of-school youth will not be achieved by using business-as-usual approaches. Instead, there needs to be a new vision for education: one in which learning happens for everyone, everywhere. The COVID-19 crisis has further exposed the weaknesses of education systems around the world and underlined the urgency to act. The PISA-D data have shone additional light on the issue. Too many education systems are not delivering even basic skills for all children, let alone preparing them for the demanding world they will live in as adults. A renewed policy approach is required to address the educational challenges of today while helping countries lay the groundwork to seize tomorrow’s opportunities. This policy approach needs to consider the five interrelated pillars of a well-functioning education system: learners, teachers, learning resources, schools, and system management. Investments and reforms in each of the pillars are needed today to lay the foundations for the future of learning. For some educational systems, the transformation of education delivery may seem far off and maybe unattainable in the short run. However, policymakers can implement key policy actions today to lay the foundations for the future of learning. The youth of today deserve no less.

Join the Conversation