Family in a rural open air home

Family in a rural open air home

Imagine a child born in Pakistan today – by their 18th birthday, they can expect to only be 41 percent as productive as they could be if they enjoyed complete education and full health. And a major part of this deficit happens in the first five years of a child’s life – with lack of access to good health, adequate nutrition, early stimulation and learning opportunities, responsive caregiving, and safety and security.

This lack of comprehensive nurturing care from birth prevents children from reaching their full potential and has detrimental impacts on their health, learning, behavior, productivity, and ultimately, the country’s human development.

A child born in Pakistan today - by their 18th birthday - can expect to only be 41 percent as productive as they could be if they enjoyed complete education and full health.

Investments in the early years have been proven to be among the most cost-effective ways of improving life outcomes and reducing inequality of opportunity. The recently-published Pakistan Human Capital Review highlights three reasons why immediate action is needed to promote Early Childhood Development (ECD) for accelerated and sustained human capital development in Pakistan:

1. Young children in Pakistan are developing less well than their low- and middle-income country peers, eroding their potential to grow and learn

Outcomes for child health, nutrition, and education are persistently low in Pakistan compared to other countries, and particularly disadvantaged children in poor households and rural areas. To illustrate, over 40 percent of children under 5 years in Pakistan are stunted – the worst rate of stunting among similar low- and middle-income countries.

Similarly, when it comes to early learning, fewer than one-fifth of Pakistan’s preschool-age children are currently enrolled in preprimary education. For those attending school, data on learning outcomes, while scarce, is a cause for concern. Low school readiness levels are associated with poor achievement scores in early primary school as evidenced by high learning poverty rates – which is expected to rise from 75 percent to 79 percent, given learning losses due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Over 40 percent of children under 5 years in Pakistan are stunted - the worst rate of stunting among similar low- and middle-income countries.

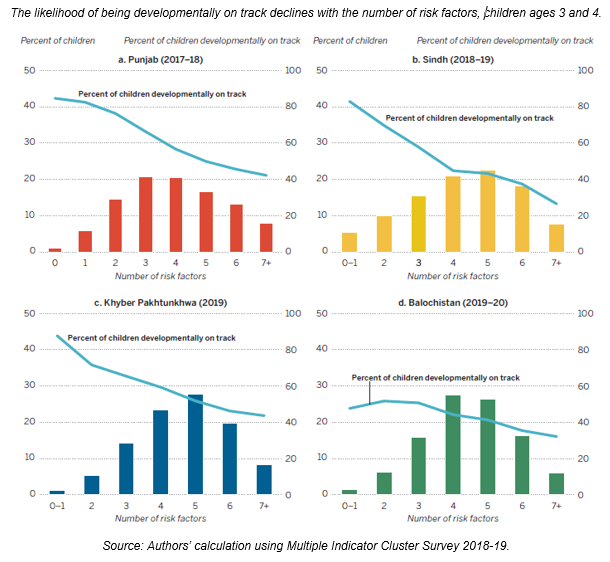

Several risk factors threaten children’s development in Pakistan, including poverty, child stunting, living in a rural area, disability, low maternal education, low levels of early stimulation at home, harsh disciplining, and lack of access to early childhood education. Each of these risks is independently associated with unfavorable ECD outcomes and, as the number of risk factors increases, outcomes worsen. In Pakistan, one in every five young children in each province experiences at least four risk factors.

In Pakistan, one in every five young children in each province experiences at least four risk factors that threaten childhood development.

2. Multiple crises such as the 2022 floods and COVID-19 pandemic have heightened the risks to young children in Pakistan

The 2022 floods have deepened the learning crisis in Pakistan, resulting in more than 24,000 schools being damaged or destroyed, and disrupting schooling for approximately 3.5 million children. The Post-Disaster Needs Assessment estimates recovery and reconstruction needs to the tune of US$918 million, which are likely to be higher once a detailed, facility-by-facility needs assessment is conducted by school heads themselves.

Flood-imposed damages come at a time when the pandemic had already disrupted early childhood care and education services and heightened the risks to children at multiple levels. For instance, between September 2020 and February 2022, schools in Pakistan were fully closed for 259 days, and partially closed for 168 days, significantly disrupting learning.

Income loss and food insecurity have also been widespread during the pandemic. And income loss is associated with greater parental distress - not getting enough sleep, worrying, feeling irritated or angry, being nervous or anxious, and not being affectionate to their child - which is in turn associated with poorer child development levels.

The 2022 floods have deepened Pakistan's learning crisis, disrupting schooling for approximately 3.5 million children.

3. The cost of inaction far outweighs the cost of investing in ECD

Failing to take action to support Early Childhood Development in Pakistan is likely to have lasting human capital costs. Consider the example of early childhood education. Failing to achieve what peer countries have already managed to achieve – preprimary education for roughly two-thirds of eligible children – will cost Pakistan 1.79 percent of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for every cohort that continues to be deprived of quality, age-appropriate education. This conservatively amounts to US$4.71 billion for each cohort of 3-5 years old children. Failure to achieve the Sustainable Development Goal of at least one year of universal preprimary education could cost as much as 3.39 percent of the country’s GDP for each cohort.

Investments in the early years will thus be critical if Pakistan is to realize its national priorities.

In Pakistan, policy and program environments that should support ECD are uneven across four core sectors: health and nutrition, water and sanitation, education, and social protection. In addition to varying capacity and resources between provinces, the challenges presented by the multisectoral nature of ECD – together with insufficient financing, inadequate workforce development, unequal parenting capacity, and lack of coordinated quality assurance systems – impede adequate and quality ECD investments in the country.

Investments will need to focus on caregivers, program coverage and program quality – including cross-cutting and multi-sectoral ECD efforts such as the integration of high-quality, contextually relevant parenting programs into existing health, social protection and education platforms from gestation to age 8.

But the first step is recognizing the need to seize the moment, and act now.

This blog is part of a series based on the Pakistan Human Capital Review: Building Capabilities Through Life.

Join the Conversation