Earth’s landscape has been subjected to both natural and anthropogenic fires for millions of years.

Natural, lightning-caused fires are known to have occurred in geological time continuously at least since the late Silurian epoch, 400 million years ago, and have shaped the evolution of plant communities.

Hominids have used controlled fire as a tool to transform the landscape since about 700,000 years ago. These hominids were Homo erectus, ancestors of modern humans. Paleofire scientists, biogeographers and anthropologists all agree that hominid use of fire for various purposes has extensively transformed the vegetation of Earth over this period.

The nature of Earth’s modern-day biomes would be substantially different if there had been no fires at all. William Bond and colleagues (2005) used a Dynamic Global Vegetation Model to simulate the area under closed forest with and without fire. They estimated that in the absence of fire, the area of closed forest would double from the present 27% to 56% of present vegetated area, with corresponding increase in biomass and carbon stocks. This would be at the expense of C4 grasslands and certain types of shrub-land in cooler climates.

Native peoples have extensively used fire in recent millennia to shape their habitats. For instance, Native Americans used fire throughout the continent to increase the production of berries, seeds, nuts and other gathered foods for their subsistence (Krech 1999 – The Ecological Indian). In Australia, Garry Cooke and colleagues (2011) have similarly documented the complex Indigenous fire management practices of aboriginal tribes whose history of migration to the continent goes back about 50,000 years before present. In both cases, the arrival of Europeans resulted in a vastly different outlook on land management. Fire suppression policies began to be enforced.

In India, too, the tribal people traditionally used fire as an essential part of land (including forest management). European foresters trained in silvicultural practices that saw fire as a hindrance to tree growth began enforcing fire suppression policies in Indian forests. Fire suppression went beyond timber production – to quote Stephen Pyne (1994), “to control fire was to control native populations”. “All fire is bad” eventually became an integral part of India’s conservation discourse and continued into the period since Indian Independence.

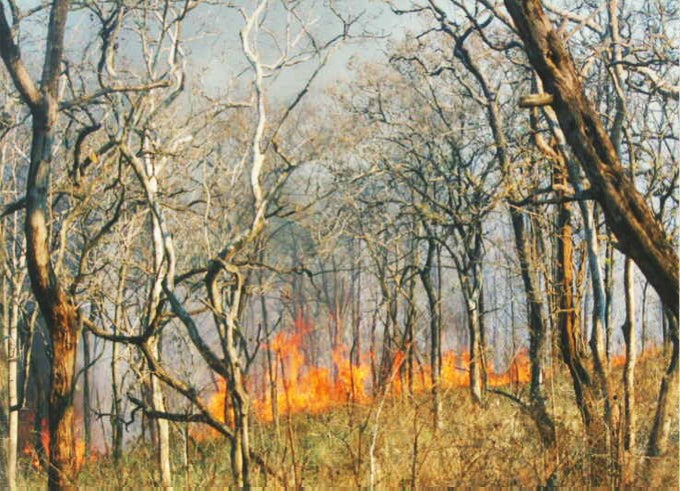

Dry forests cover a major part of India’s land surface. Given the dense human population and various anthropogenic activities, it is extremely difficult to keep fire out of forests for any reasonable length of time. Lightning-caused fires also happen in Indian forests, especially in the north, though the extent and frequency are not known.

Fires are most destructive when they occur late in the dry season, under conditions of high temperature and low humidity. The universal fire suppression policy of the forest department in all forest types (the exceptions being grassland of the floodplains) results in a build up of fuel load (litter, grass and woody debris) over the years. Fires are successfully prevented for several years increasing the fuel load. Then, a combination of low humidity and high temperatures late in the dry season creates the perfect conditions for a very high intensity and destructive fire when a deliberate or careless action by people sets the ground vegetation on a high temperature fire with the potential to cause a canopy fire.

There is increasing scientific evidence that the invasion of woody plants such as Lantana camara in southern Indian forests is the result of fire suppression over the years with consequent high intensity fires.

Should we control fires? YES.

However, a pragmatic fire management policy for dry forests should look at the option of learning from indigenous fire management practises such as early dry season, cool burning to avoid late dry season high temperature fires.

Much research is needed on fire management.

We should not be afraid of using fire judiciously as tool to manage forest fires to achieve broader goals of increasing forest diversity, biomass and carbon stocks. Mere fire suppression will not serve the purpose as the experience with many developed countries (USA-California, Portugal, Spain, Greece, Australia) has shown in recent years (all these have experienced highly destructive fires in recent years).

Tropical moist forests such as rainforests should, of course, be strictly protected against fires.

On November 1-3, India’s Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) and the World Bank organized a workshop in Delhi to discuss forest fire prevention and management. The workshop brought together fire experts and practitioners from eight countries along with Indian government officials from the ministry and the state forest departments, as well as representatives from academia and civil society. This blog is by a Senior Indian Scientist who attended this workshop. Read other blogs from this workshop here.

Join the Conversation