Vehicles moving amidst heavy smog in Delhi, India. Photo: Saurav022 / Shutterstock.com

Vehicles moving amidst heavy smog in Delhi, India. Photo: Saurav022 / Shutterstock.com

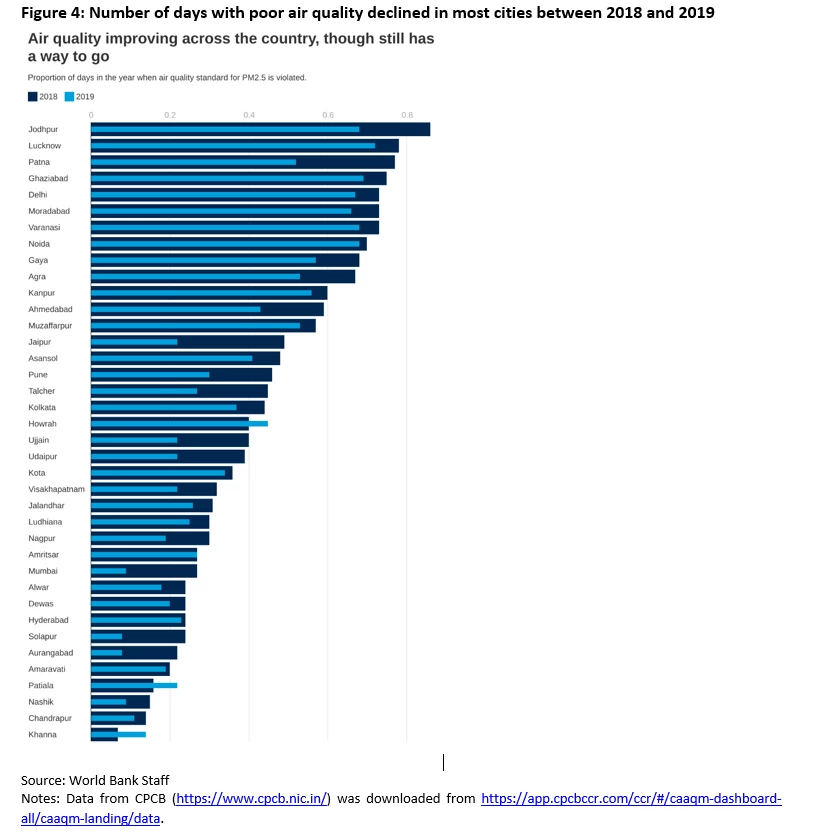

India is home to some of the world’s most polluted cities. An unintended but welcome consequence of the lockdown to contain the coronavirus has been improved air quality throughout the country. Our assessment of India’s air quality trends has found another underlying and positive trend: air quality has been improving across the country since 2018, and this has nothing to do with the COVID-19 lockdown.

Growing Threat of Air Pollution

Poor air quality has come to be recognized as a serious health risk and drag on economic development in India. Air quality has been deteriorating across the country since the 1990s, and in 2017 as much as 97 percent of the country’s population was estimated to be exposed to unhealthy levels of ambient PM2.5. Though there are many types of air pollutants, these small particulates in the air, about one-thirtieth the width of a human hair, are the most harmful to human health. They can penetrate deep into the lungs, enter the bloodstream and cause deadly illnesses such as lung cancer, stroke, and heart disease.

In 2017, only one-third of India’s cities met the national standard for annual concentrations of PM2.5 – which is, on average, 40 micrograms per cubic meter. Furthermore, the health impacts of pollution represent a heavy cost to the economy. According to World Bank estimates loss of welfare from PM2.5 pollution is estimated to be equal in magnitude to 5.9 percent of GDP.

Air quality has been improving across the country since 2018, and this has nothing to do with the COVID-19 lockdown

Cleaner Air Due to Lockdown

The economic lockdown to contain COVID-19 brought unexpected relief from poor air quality. Reports of clear bule skies have emerged from across the country.

Articles studying satellite data across India (figure 1) have shown a 15 percent reduction in nitrogen-dioxide (NO2) concentration levels around the time of the shutdown (March 15 to April 30) from those in 2019 for the same period. This was in large part due to vehicular traffic, one of the main sources of NO2 emissions, coming to a halt due to the lockdown.

Satellite data on another pollutant, sulfur-dioxide (SO2), show similar trends. Comparison of average concentration levels during the months of February to April between 2019 and 2020 (figure 2) shows a reduction in SO2 level, likely the result of reduction in power production (with power plants denoted by black dots) and a major source of SO2 emissions.

Both NO2 and SO2 are precursor pollutants that lead to the generation of secondary PM2.5, and so reductions in concentrations of these pollutants is a welcome trend. But because PM2.5 is also emitted directly from combustion of fossil fuels and biomass, and natural dust contributes to its levels, it is important to also consider impact on PM2.5 concentrations in addition. Our assessment shows that lock down has also reduced PM2.5 levels in most cities (figure 3).

Improved air quality since 2018

World Bank analysis of air quality trends in India since 2018 has revealed another broader trend that has been missed so far: air quality has been improving consistently across the country since 2018, and this has nothing to do with the lockdown.

The number of days when air quality concentrations violated the daily national standard for PM2.5 across the country were consistently lower in 2019 compared with 2018. Where Patna in Bihar saw 70 percent of days in 2018 recording poor air quality, less than 50 percent of days in 2019 recorded poor air quality. Delhi, Mumbai, and Kolkata, India’s largest metropolitan cities, all saw a decline over the same period.

What is driving this decline? Is it the impact of government’s policies over the years to address air pollution? Is it changes in the economy, the slowdown and potential change in economic structure? Or could it simply be the result of meteorological conditions?

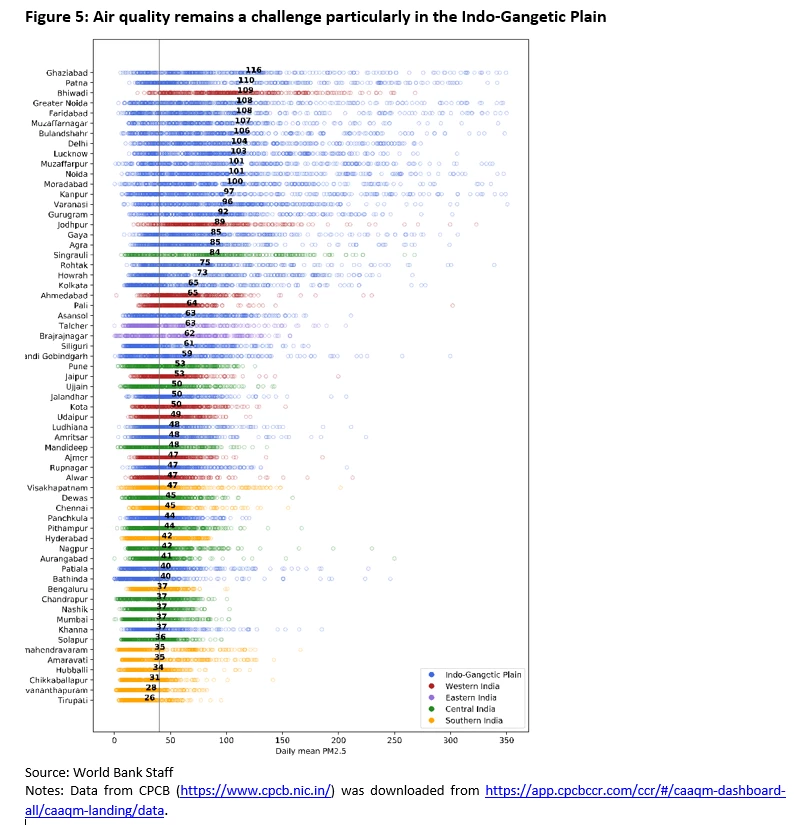

Air quality remains a challenge (figure 5), and at levels far above the World Health Organization's guidelines for healthy air especially in the Indo-Gangetic Plains. Understanding what is driving the improvement is critical to inform government policies and programs to address it. We plan to explore this in our forthcoming research.

Join the Conversation