There is now a huge window of opportunity for South Asia to create more apparel jobs, as rising wages in China compel buyers to look to other sourcing destinations. Our new report – Stitches to Riches?: Apparel Employment, Trade, and Economic Development in South Asia – estimates that the region could create 1.5 million new apparel jobs, of which half a million would be for women. And these jobs would be good for development, because they employ low-skilled workers in large numbers, bring women into the workforce (which benefits their families and society), and facilitate knowledge spillovers that benefit the economy as a whole.

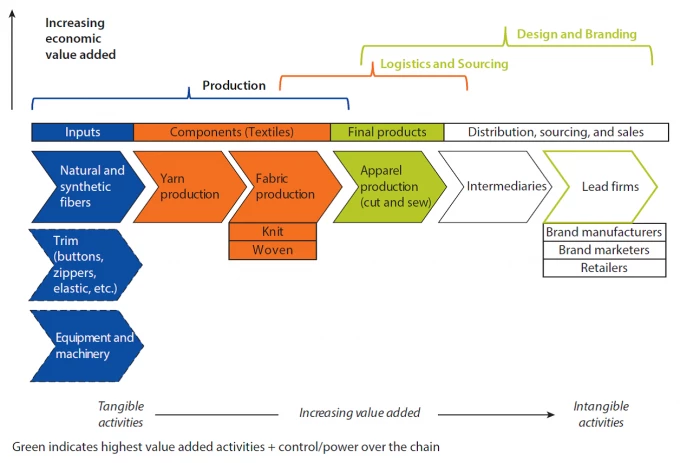

But for these jobs to be created, our report finds that apparel producers will need to become more competitive – chiefly by (i) strengthening links between the apparel and textile sectors; (ii) moving into design, marketing, and branding; and (iii) shifting from a concentration on cotton products to including those made from man-made fibers (MMFs) – now discouraged by high tariffs and import barriers. These suggestions recently drew strong support from panels of academics and representatives from the private sector and government when the report was launched mid-year in Colombo, Delhi, Dhaka, and Islamabad. South Asia is now moving on some of these fronts but a lot more could be done.

Moving up the apparel value chain

Stitches to Riches? finds that South Asia’s abundant low-cost labor supply makes it extremely cost competitive (except for possibly Sri Lanka). But rapidly rising living costs in apparel manufacturing hubs, coupled with international scrutiny, are increasing pressure on producers to raise wages. Plus, countries like Ethiopia and Kenya, who enjoy a similar cost advantage, are entering the fray, and some East Asian countries already pose a big challenge. The good news is that the policy reforms needed to keep the apparel sector competitive would likely benefit other export industries and transform economies (view end of the blog).

Figure 1: Structure of the Global Value Chain for Apparel

Some strategic moves for South Asia

India has made significant strides in developing backward links to the textile industry with its missions on cotton and technical textiles. Plus, the Technology Upgradation Funds Scheme (TUFS) provides capital investment support for modernizing textile production. However, India has yet to move into MMFs, meaning that apparel exports are concentrated in the spring/summer season, with factories operating for only 6.5 months (versus the global average of 9).

Pakistan has been less successful in integrating the apparel and textile sectors. It did launch a policy similar to TUFS, but results were mixed, with firms citing implementation issues and high interest rates. While large firms tend to offer in-house training, Pakistan lacks a national scheme for training in high value-added activities. It also remains heavily concentrated in cotton products.

Bangladesh, which specializes in low-value and mid-market price segment apparel, must contend with high attrition and a lack of skills training for employees, forcing producers to hire foreign nationals (who are more expensive) as managers. Plus, there is a lack of upward mobility for women, and a heavy concentration on cotton products.

Sri Lanka has perhaps progressed the most in moving up the value chain. Apparel specific-training institutes provide courses in textile and apparel technology, quality control, product development, and merchandizing – and producers have moved into design and retail, launching their own international brands like Avirate and Amante. Looking ahead, Sri Lanka, which does produce MMF products, can position itself as a regional hub to facilitate sourcing for international buyers.

Apparel: A first step to industrialization

Historically, developing countries have used success in apparel production as a first step toward industrialization. The experience gained allows them to progress from light manufacturing (apparel, footwear, and toys) to producing more sophisticated products (plastics, electric machinery, and electric parts) – as illustrated in Kaname Akamatsu’s “flying geese model” (1962) (figure 1.2). Countries like Japan and the ASEAN 4 start off manufacturing nondurable consumer goods like apparel and then progress to durable consumer goods, and then capital goods of higher value. Economists contend that the apparel sector (along with footwear and textiles) was instrumental in the initial development of countries like Germany, Japan, Malaysia, the Republic of Korea, Singapore, the United Kingdom, the United States, and more recently China, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Vietnam (Brenton and Hoppe 2007).

Figure 1.2: “Flying Geese” Model Depicts the Process of Industrialization for Developing Countries

For more information, read the report.

Join the Conversation