A boy wearing a mask attends an online class.

A boy wearing a mask attends an online class.

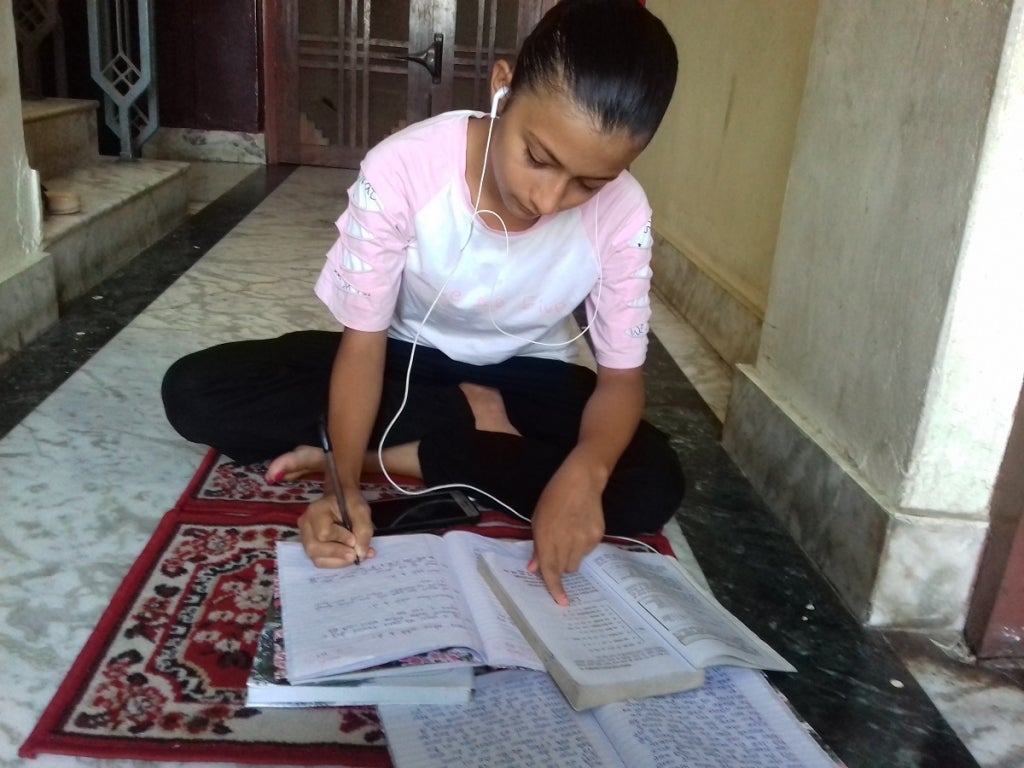

Sikshya Kafle, who lives in Banke district in Nepal’s Terai, was waiting eagerly for her spring break.

But this year is different, as her school closed early. On March 19, in fact, Nepal officially closed all educational institutions to help contain the spread of COVID-19. A nationwide lockdown followed four days later.

“I miss my friends, and I am worried about missing out on learning,” says the ninth-grader.

Since March, the pandemic has kept an estimated 8.2 million Nepali children away from their classrooms, jeopardizing their progress in education.

Even before the coronavirus, Nepal was in the midst of a learning crisis, as more than half of the country’s students were not proficient in reading.

Now the pandemic may worsen further education outcomes, increase dropout rates, and leave behind the most vulnerable students.

Betting on remote education

In this difficult context, Nepal has placed education at the center of its COVID emergency response and has pursued remote and e-learning opportunities to offset school closures.

To that end, the World Bank recently organized an EdTech session to discuss remote learning solutions for Nepal, where the digital divide is high. Participants showed enthusiasm for various technologies, including radio, mobile phone, television, and online options, that can support education continuity.

Nepal has placed education at the center of its COVID emergency response and has pursued remote and e-learning opportunities to offset school closures.

One example is the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology’s learning portal, which features digital content like interactive learning games, videos of classroom lessons, audio, and e-books. This content is categorized according to grade and subject for easier navigation and is overseen by Nepal’s Curriculum Development Center.

Recently, the ministry has also developed and published new guidelines to facilitate students’ learning through alternative means.

To address the critical learning gap facing children during the COVID-19, a coalition of teachers, education journalists, nongovernmental organizations, local governments, and local radio stations has also launched a distance-learning radio program called Radio Schools. Across five districts, this is benefiting more than 100,000 children in grades 1-10.

“The radio classes use a mix of educational and entertainment elements to deliver classes on science, math, English, Nepali, and social studies,” noted Dr. Laxmi Paudyal, an Education Advisor at Save The Children Nepal and an EdTech participant. “We have seen great participation of students through phone calls, quiz contests, and through social media discussions,” she added.

For Shikshya, the radio school was a new experience and provided great relief.

A coalition has also launched a distance-learning radio program called Radio Schools. Across five districts, this is benefiting more than 100,000 children in grades 1-10.

“I used to connect with my friends through a mobile phone, and now I actually use it to connect to the radio school program regularly,” she says. “I can’t wait to attend the speech competition that is happening in my next class. I am going to talk about the effect of federalism in my community,” Shikshya adds with excitement.

Closing the learning gap

Fewer than half of Nepal’s households have access to broadcast or cable television. Computer and internet access is low and uneven across provinces, ethnicities, and socioeconomic backgrounds. About a third of families own radios.

But mobile phone penetration is high—more than four in five households in Nepal have these devices, a number consistent across provinces—making it possible for children to use phones to connect to local radio that’s broadcasting learning programs.

“Most of the students have a cellphone in their home, which they are now using to access the radio schools,” says Shanti, who also teaches lessons in Nepali at the local radio station every Sunday. “The crisis has brought local teachers together, where we take turns to prepare and deliver lessons through the radio station.”

In the short to medium term, inclusive content for students with disabilities in all grade levels should be a priority. Devices with uploaded educational content could also be supplied to the most marginalized children who can’t access any form of media.

Since internet connectivity is a severe bottleneck in Nepal, arrangements can be sought with internet and telecom providers to provide zero-bandwidth or zero-cost access to learning portals. This will require that new servers and network hardware be set up in many provinces to handle higher traffic. Teachers also need to receive adequate training to master the technology so that they can provide support to children with remote learning tools and materials.

COVID-19 has tested the limits of Nepal’s education system, and much progress remains to be made to improve children’s learning.

But the pandemic has also revealed how quickly the country could stand up to the challenge to ensure that children can continue their education now and be better able down the road to contribute to a more prosperous Nepal.

Join the Conversation