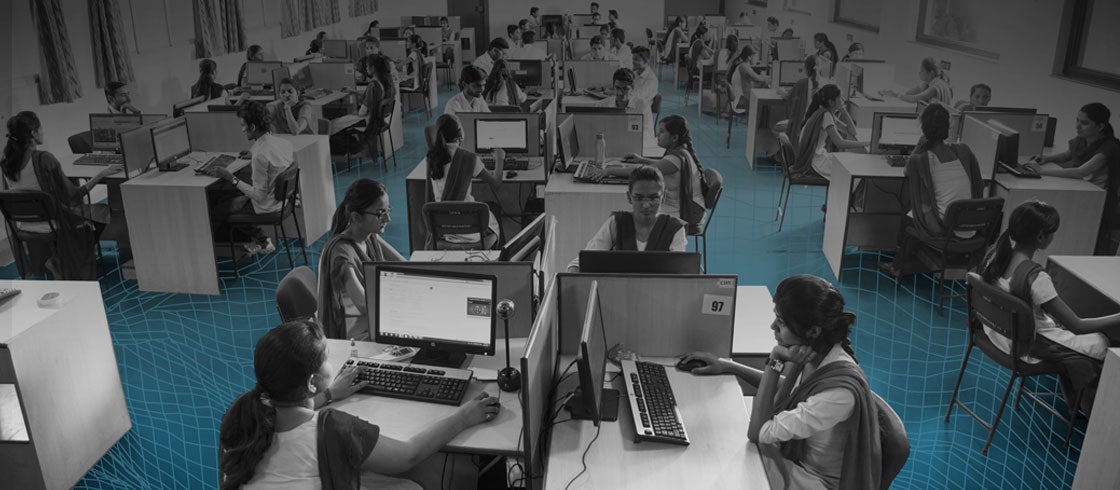

South Asia's services sector got a boost during COVID-19 in large part due to a massive digital boom triggered by more consumers going online for goods and services. Photo: CRS PHOTO / Shutterstock.com

South Asia's services sector got a boost during COVID-19 in large part due to a massive digital boom triggered by more consumers going online for goods and services. Photo: CRS PHOTO / Shutterstock.com

It’s no secret for those working at the World Bank—and for that matter in the development world—that we have our own Esperanto of acronyms. These acronyms come and go. And even I, after twenty years at the World Bank, find myself googling these new acronyms during meetings to follow the discussion. Often, once you have learned a new acronym, it has fallen out of favor again. However, there’s (a new) one that’s here to stay and even poised to become part and parcel of South Asia’s growth strategy: GRID. Introduced at the IMF-World Bank Spring Meetings earlier this year, GRID stands for Green, Resilient, and Inclusive Development. GRID offers South Asian countries a real opportunity to implement lessons learned from the COVID-19 crisis and enable a long-term economic recovery across the region . Our latest South Asia Economic Forecast or SAEF (yes, another acronym, though aptly titled!) Shifting Gears: Digitization and Services-Led Development captures South Asia’s burgeoning digital vibrancy and increasing role of services during the COVID-19 pandemic and makes the case for how both can lay the foundation for sustained future growth in the region.

Green, resilient, and Inclusive development offers South Asian countries a real opportunity to implement lessons learned from the COVID-19 crisis and enable a long-term economic recovery

GRID lessons from the pandemic

It’s clear that part of building back better after the pandemic for South Asia requires the region to prepare more effectively for extreme future events including natural or manmade disasters , given that South Asia, specifically India, along with sub-Saharan Africa accounted for most of the increase in poverty worldwide, reversing years of progress on this front. That puts at the forefront for the region, the need to establish universal social safety nets to protect families during crises and urgently adapt and mitigate policies to reduce the impact of climate change.

These are the green (G) and resilient (R) parts of GRID.

Secondly, it became clear during the pandemic that disasters tend to hit poor and vulnerable people—mostly part of the informal sector—disproportionately. In the case of COVID-19, social distancing for domestic migrants, street vendors, and slum dwellers across South Asia was virtually impossible. They could not work remotely and had limited access to disinfectants and healthcare.

At the same time, children in rural areas dropped out of school with little opportunity to take advantage of remote learning. A high percentage of girls who dropped out will most likely not return to school. These social divides must be narrowed in the new normal to prevent ruptures in the social contracts.

This is the inclusive (I) part of GRID.

Third, South Asia undeniably has a new economic reality: the incredible potential for growth in the services sector. The services sector got a boost across South Asia during the COVID-19 pandemic in large part due to more consumers going online for goods and services, thereby contributing to a massive digital boom . It therefore behooves South Asia to shift gears from a traditional manufacturing-led growth model—which has historically been a struggle—and capitalize on the potential of its services sector coupled with the area’s digital vibrancy. Bear in mind that almost 50 percent of the value added in the exports of goods in South Asia already comes from services. In 2019, the services sector accounted for an average of 55 percent of GDP and 45 percent of employment in developing economies. This means that services can (1) generate—directly or indirectly—substantial export revenues; (2) indirectly impact productivity of other sectors through the adoption of digital platforms; and (3) create jobs as well as facilitate the upgrading of employment skills.

While this is good news overall for South Asia, fully exploiting economic growth from services calls for a rethinking of institutions and regulations to ensure that they create conditions where creativity and innovation are truly supported.

The services sector is likely to be the new fuel for the Development (D) part of the GRID.

Fully exploiting economic growth from services calls for a rethinking of institutions and regulations to ensure that they create conditions where creativity and innovation are truly supported

GRID is far from a theoretical concept, as you can see. Granted, we have after all been talking about sustainable development in many ways for ages, but historically, there’s no better time than now to implement a GRID approach to building back better so we may hope to not have another annus horribilis like 2020 across South Asia.

Nepal has already implemented a GRID-SAP or a Strategic Action Plan to leave no one behind in the nation’s economic recovery. Here’s hoping that more nations across South Asia embrace the new GRID on the block and build back in a green, resilient, and inclusive manner.

This blog is part of a series centered around the latest edition of our South Asia Economic Focus (SAEF)- Shifting Gears: Digitization and Services-Led Development.

Join the Conversation