Blog #10: Three job deficits in unfolding India story

India is home to the largest number of poor people in the world, as well as the largest number of people who have recently escaped poverty. Over the next few weeks, this blog series will highlight recent research from the World Bank and its partners on what has driven poverty reduction, what still stands in the way of progress, and the road to a more prosperous India.

We hope this will spark a conversation around #WhatWillItTake to #EndPoverty in India. Read all the blogs in this series, we look forward to your comments.

Rising labor earnings have driven India’s recent decline in poverty. But the quantity and quality of jobs created raise concerns about the sustainability of poverty reduction, and the prospects for enlarging the middle class. The period after 2005 can be best described as one of a growing jobs deficit. Three deficits actually: i) a deficit in the overall number of jobs, ii) a deficit in the number of good jobs, and iii) a deficit in the number of suitable jobs for women.

The rapid decline in poverty in India between 2005 and 2012, the most recent period for which data are available, was driven mainly by higher labor earnings. This is not surprising given that the capacity to work tends to be the main – and often the only – asset of poor households. Over this period, wages for unskilled workers increased sharply. There was also a marked shift towards non-farm jobs, which on average pay more than jobs in agriculture. These two trends gave a substantial boost to labor earnings and propelled millions of Indian households above the poverty line. While this was indeed a spectacular achievement, there are reasons to worry about its long-term sustainability.

A large majority of those who escaped poverty did not gain entry into the middle class. Instead, they moved slightly above the poverty line and remain vulnerable to slipping back. The deficit in the number of jobs created after 2005, as well as in their quality, explains these high levels of vulnerability. This period can, therefore, be described as one of a growing jobs deficit. Or rather three of them, as we discuss in a recent paper: i) a deficit in the overall number of jobs, ii) a deficit in the number of good jobs, and iii) a deficit in the number of suitable jobs for women.

An overall deficit of jobs

While all three deficits can be traced to the pattern of India’s economic transformation during this period, they are better appreciated from a statistical point of view. Between 2005 and 2012, net job growth in the economy was 0.6 percent per year. This was much less than the growth in the working age population that was not in school – which stood at 1.9 percent per year. In absolute numbers, of these 13 million potential entrants into the workforce every year during this period, only 3 million got a job. In a young and increasingly aspirational society, this growing jobs deficit has the potential to turn the much-awaited demographic dividend into a demographic curse.

A deficit of good jobs

On closer examination, it is not as if job creation came to a standstill after 2005. On the contrary, there was considerable dynamism in the informal segments of the economy, especially in rural areas. As could be expected in a phase of structural transformation, there was a substantial decline in employment in agriculture, with nearly 34 million farm jobs lost between 2005 and 2012. Meanwhile there was a boom in construction jobs, which accounted for nearly half of the expansion in non-farm employment. However, construction jobs tend to be casual. Their wages are set on a daily basis, or through short-term contracts, and they provide no form of social protection. While jobs like these help people escape poverty, they do not take them much further than that.

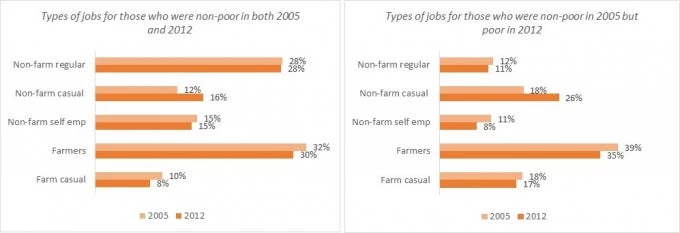

Source: Based on the Indian Human Development Survey (IHDS), 2005 and 2012.

Instead, transitions into the middle class are associated with regular, salaried jobs. The likelihood of a household durably escaping poverty between 2005 and 2012 was higher if a larger share of its members had regular jobs (figure 1). On the other hand, households that slipped into poverty between these two years saw a growing share of their family members employed as casual workers.

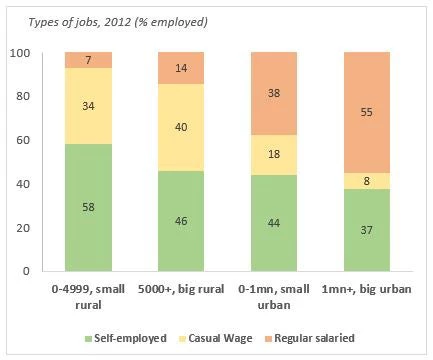

In principle, urbanization brings with it the promise of better jobs. In India too, it is true that large urban areas have a substantially higher share of regular jobs (figure 2). By contrast, small towns have far fewer regular jobs to offer, and in rural areas these jobs are rare. Therefore, unless small towns and large villages, where most of India’s poor and vulnerable live, can ensure the vibrant creation of regular jobs, building a sizeable middle class could remain an elusive goal for the country.

While big cities have the highest share of regular jobs, they also have the largest overall jobs deficit. In fact, when moving from small villages to large cities, the scarcity of jobs relative to the working age population not in school increases across the rural-urban gradation. So, how can one reconcile this larger share of regular jobs with an altogether greater scarcity of good jobs? The answer is simple: in urban areas the share of regular jobs may be greater among those who are employed, but fewer people are at work in these places relative to the working age population. And, in urban locations, it is mainly the women who are not working.

A deficit in suitable jobs for women

This brings us to the third deficit - the scarcity of suitable jobs for women. Historically, India’s female labor force participation rates in urban areas have been low - hovering around 20 percent. But one of the most striking developments after 2005 has been the large withdrawal of women from the rural labor force. As rural areas become increasingly urban, they are beginning to look increasingly urban in the magnitude of their jobs deficit too. By contrast, in small villages over 70 percent of women are employed on the farm, as agricultural activities continue to be important in these areas. Elsewhere, however, manufacturing tends to be the largest employer of women outside of farming. In towns and cities, on the other hand, women more often hold professional jobs in health, education and public administration. In these areas, construction work, while significant, does not employ too many women.

Source: Based on the National Sample Survey (NSS), 2012 and Population Census, 2001.

The structure of female employment by sector is revealing of the kinds of jobs that are seen as more suitable for women. For instance, women are more likely to work when jobs are located close to their homes and allow multi-tasking, as in the case of farming. They are also more likely to work when jobs offer regular wages, as in the case of manufacturing. Or when jobs have social protection benefits attached to them, as in case of the health, education and public administration, where the public sector is the dominant player. Unfortunately, such jobs are few and far between.

Reference:

Urmila Chatterjee, Rinku Murgai and Martin Rama (2015) “Employment Outcomes along the Rural-Urban Gradation in India.” Economic and Political Weekly, Vol 50(26-27): 5-10, June 27.

This blog was originally published in the Indian Express on 25th July, 2016.

Join the Conversation