As leaders from government, private sector, civil society, and development agencies gather in New York for the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA), climate change is being featured strongly; both through the main program and a dedicated summit. At UNGA, world leaders also adopted a political declaration on accelerating action to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including SDG7, which focuses on ensuring affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all by 2030. At the intersection of the two priorities of climate change mitigation and achieving SDG7 lie untargeted energy subsidies, which are suboptimal policy tools that risk diverting governments further away from these critical objectives, rather than helping achieve them.

The sequence of events that followed the commodity price shocks in 2022 illustrate what happens when external shocks disrupt the delicate balances that enable reliable, affordable, and sustainable supply of energy to households and businesses. In response to the food and fuel crisis, governments around the world deployed various measures to mitigate the impacts of commodity price shocks and broader global inflationary pressures on their economies and societies, and energy subsidies comprised a substantial share of those measures. Consequently, after declining for several years, energy subsidies have been increasing worldwide over the past two years, reaching an all-time high of $1 trillion by the end of 2022.

Energy subsidies often have significant negative impacts, making their reform a central topic at the nexus of energy, climate, and macro-fiscal reform agendas for many countries. When end-user energy prices are kept lower than the efficient cost of supply, the benefits of those price subsidies accrue to all consumers, rather than those who need it the most. For energy commodities that are consumed in higher amounts by better-off households compared to the poor, such as gasoline, the better-off households capture a greater share of the benefits from those energy price subsidies. Moreover, energy subsidies, in particular those that support the consumption and production of fossil fuels, not only divert limited fiscal resources from other government priorities but also can lead to greater harm to the environment and undermine climate change mitigation efforts.

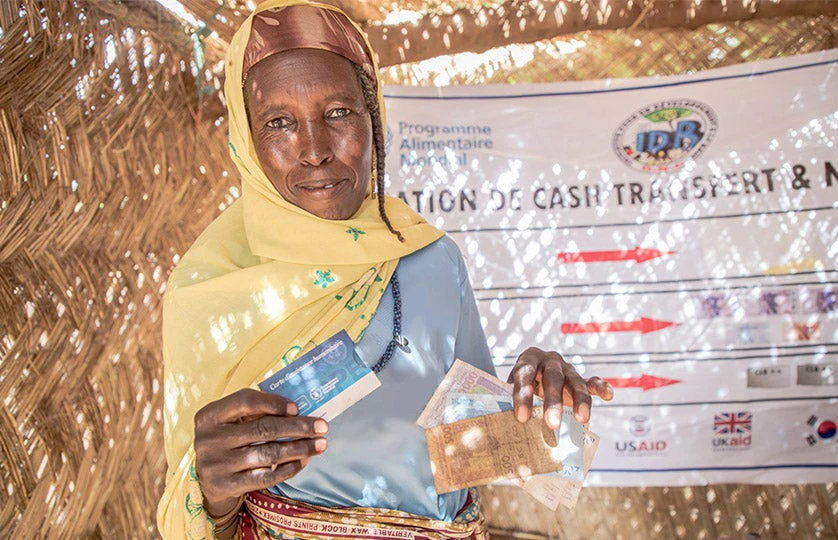

The good news is that there are better alternatives to broad-based price subsidies, as experience in many of our client countries shows. Fortunately, policy tools that allow more efficient, effective, and fiscally and environmentally sustainable ways to protect the poor and vulnerable do exist. Among these tools, cash transfers, which involve providing households with direct payments to meet their needs, have stood out as a solid option with a strong track record.

Governments around the world have deployed cash transfers to support energy subsidy reform efforts over the past few decades, as explored in the ESMAP Technical Paper titled “Cash Transfers in the Context of Energy Subsidy Reform: Insights from Recent Experiences, prepared by colleagues from the World Bank’s Social Protection and Jobs and Energy and Extractives Global Practices. Our two teams collaborated to better understand how cash transfers have been deployed to mitigate impacts of energy subsidy reforms, particularly on the poor, the vulnerable, and those in need.

Real-world reform experiences reveal that well-designed cash transfers have proven to be highly effective in mitigating reform impacts and supporting implementation of reforms in diverse country settings. In this context, individual country experiences render interesting insights on program design and implementation. A good example comes from the Dominican Republic, where, drawing on quantitative analyses of potential impacts of energy subsidy reform options under consideration, the government deployed targeted cash transfers to key sectors and households in order to mitigate the potential impacts identified, and gradually integrated these programs into the country’s social protection system over time. Similarly, in the 2014-16 period, in a challenging macrofiscal context, the Government of Ukraine successfully leveraged the country’s existing social assistance system to support households, while undertaking ambitious reforms affecting key energy services.

It is clear that social protection has an important and growing role to play in helping governments respond to shocks and supporting reforms in the energy sector. These country experiences highlight the importance of investing time and resources to design programs that are right for the reform circumstances. They show that there are tradeoffs between coverage and generosity of cash transfers and fiscal savings from reform, and clear, effective, and targeted communication are critical for furthering reforms.

Looking into the future, the focus on meeting the most immediate needs in the short term must be complemented with an emphasis on longer term resilience. In the short term, compensating households through cash transfers can play a crucial role in mitigating potential impacts and facilitating reform implementation. In the long term, it is essential to prioritize strengthening the resilience of households and the economy against future shocks, both from an energy and a social protection lens.

Better policies, programs and systems in social protection and jobs will be an essential component of a just transition to a lower carbon future, alongside decisive action in the energy sector to scale up affordable, secure, and reliable clean energy and phase down coal-fired electricity generation.

Subscribe here to stay up to date with the latest Energy blogs.

Join the Conversation