Poland has been one of the most active and steady reformers of its business environment in the world, but firms are yet to benefit from reforming the country’s burdensome business inspections.

According to the World Bank’s Doing Business report, Poland ranked 74 th globally in the ease of doing business in 2006. It took 10 procedures to incorporate a business in Warsaw, more than 40 steps to pay taxes, close to 200 days to register property, and almost 1,000 days to enforce a contract. A decade later, Poland ranked 24th, higher than the EU average – progress unmatched by any high-income country in terms of ease of doing business.

Doing Business is arguably the most influential publication on the business environment, but it is not an exhaustive source of information. Its focus is to measure regulations, not interest rates, roads, or the workforce. In many areas (but not all) it records the procedures, time, and cost needed to comply with the law in a simple case (e.g., building a 1,300 square meter warehouse in the periurban area of a country’s largest city). For each of these procedures, a single estimate of the time and cost is published. The emphasis on simple cases and single numbers makes it easy to compare between countries, but inadvertently blurs important details.

A closer look at these details reveals that puzzling anomalies persist in the country’s business environment.

Take business inspections as an example. They exist to protect health and safety. Workplace inspections, for instance, should aim to prevent injuries at work, including deadly ones. According to Eurostat, around five out of 100,000 workers in the worst-performing EU countries die every year because of workplace accidents.

Preventing some of these accidents is of great benefit to society. But inspections and other enforcement measures generate costs to businesses and individual taxpayers. A review of occupational health and safety inspections in Great Britain and Germany found that between 2006 and 2013 inspections were from four to seven times more frequent in Germany, while outcomes were similar. Available evidence suggests that in Poland, just like in Germany, some of the inspection burden is unnecessary.

Desk research and interviews completed by World Bank staff in 2016 found that Poland has over 20 institutions that regularly inspect businesses, with partially-overlapping mandates and some duplication at several levels of government. Compared to international best practice, Polish inspectors tend to conduct site visits frequently, make little use of risk management tools, rely on sanctions as a primary measure for enforcement, and overlook important drivers of compliance - such as the capacity of firms to deal with a complex web of regulations.

Inspectors are required to enforce superfluous rules, which were either not removed when the acquis communautaire was adopted around 2004, or tacked onto EU regulations in the following years. These findings do not cover tax inspectorates, which come with a separate set of challenges in Poland. While air-tight evidence on the effectiveness of inspections is scarce, insights about one inspection area – occupational health and safety – can be drawn from statistics on fatal workplace accidents.

In Poland the incidence of workplace accidents is below the average for EU countries. Together with Slovakia, Poland’s workplaces rank as the safest among all member states that joined the European Union in the last two decades.

Food inspections are another case in point for disproportional inspection burden in Poland.

Five institutions keep watch over the safety and quality of Polish food, whereas in other EU member states only one institution is responsible for this task. All food-related inspectorates have offices at the level of voivodships (Poland’s 16 regions) and two institutions have offices at the level of poviats (Poland’s 380 counties).

The largest of these institutions, the Sanitary Inspectorate, conducts close to one million inspections and tests per year - a high number, given that there are slightly more than 2 million firms in Poland and not all of them fall under the supervision of the Sanitary Inspectorate.

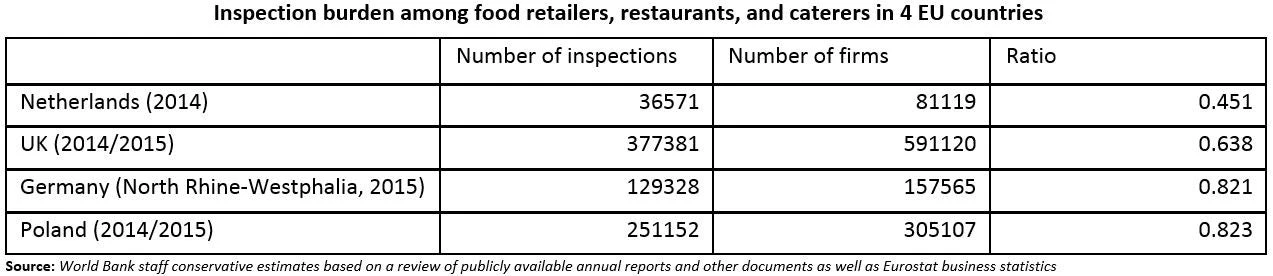

Even though EU-wide harmonization is the rule in the area of food safety, national requirements and procedures are applied on top of EU-wide regulations. The number of inspections per firm exceeds levels noted in a number of other EU countries. As the table below shows, Polish food retailers, caterers, and restaurants are inspected almost twice as often as Dutch firms, increasing costs, hampering business entry and growth, and limiting competition.

The government of Poland has recognized the need to reform business inspections and has announced the plan to merge several inspectorates as part of its Responsible Development Strategy, the government’s blueprint for reforms through 2020. The challenge in implementing this plan will be to combine changes in structures with changes in regulations and practices of inspectorates.

A review of regulations is needed to make sure that inspectors who end up working in a consolidated institution do not end up enforcing the same superfluous rules that they have been watching over in the past. Significant improvements for firms can be also achieved by unifying IT systems, risk-based planning, offering guidance to firms, and other international best practices. Poland can learn these best practices directly from its neighbors. In Lithuania, for instance, firms have been reported to have gained more from the adoption of risk management in the country’s inspectorates than from clustering and merging institutions.

The objective of inspection reform in Poland should be to save businesses time and costs without compromising effectiveness. Merging institutions is a good start, but shouldn’t be a change of plaques only.

At the end of the day the job of reformers and inspectors is quite similar – managing risks for results.

Join the Conversation