In my nearly two decades with the World Bank, I have worked through several crises. And yet the latest estimations on the social and economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic everywhere in the world have left me in utter disbelief. Where I sit in Nur Sultan, Kazakhstan, it is too early to tell the consequences of the virus in many areas, but it is already clear that the impact on student learning will be devastating.

The education system in Kazakhstan was struggling even before the pandemic struck. Before COVID-19, six out of 10 students were functionally illiterate in Kazakhstan, a higher-middle-income country where, on average, a child is expected to complete 13.7 years of schooling. The pandemic now threatens to push over 100,000 more students into functional illiteracy.

Functional literacy is not the same as “regular” literacy. Literate students can still memorize most capitals in the world or recite Mendeleev’s periodic table. But they lack the capacity to apply their knowledge—math, science, and reading skills—in their day-to-day life to function professionally and flourish both as individuals and citizens.

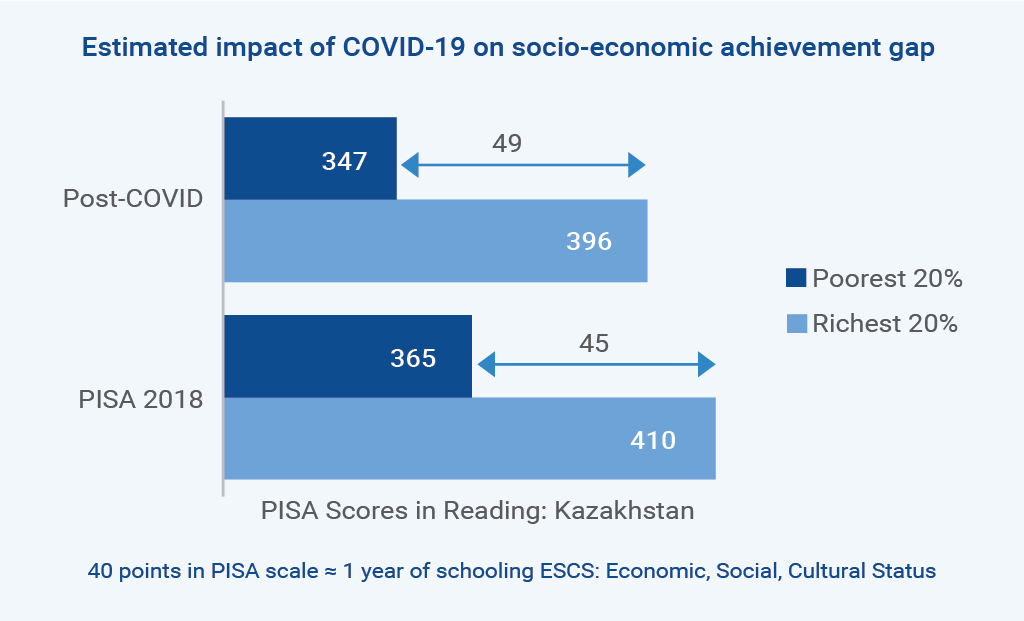

The Bank’s recent estimates for Kazakhstan also indicate that, as a result of the pandemic, learning will decline by eight PISA points. PISA is the Program for International Student Assessment study that looks at the math, reading, and science skills of 15-year-olds.

What is worse, these losses and negative implications are going to be most pronounced for the already vulnerable and disadvantaged. Even short-term school closures will widen the reading achievement gap by 18 percent between children from poor and rich households, as can be seen in our estimates in the figure below.

Inequality and the “four Kazakhstans”

Geographic inequalities often compound social ones. An uneven and unequal landscape of human capital development in Kazakhstan was presented by the Center for Research and Consulting during a discussion on the Human Capital Index (HCI) organized by the Kazakhstan Institute for Strategic Studies under the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan in early October.

The Center analysts argued that four Kazakhstans co-exist in the country, each with a different level of income, life expectancy, fertility, and other indicators that impact HCI. It was striking to see the tremendous disparities among the four different regions: for example, regarding income, there is a difference of four times between high and low performing regions, on fertility the country’s North can be compared to Europe, while the South reflects trends of low income countries, and in terms of life expectancy, the northwest of Kazakhstan is similar to sub-Saharan African countries.

PISA outcomes confirm similarly concerning differences in human capital across Kazakhstan, whereby, on average, low-performing regions are four years of schooling behind high-performing regions, demonstrating weak results both in rural and urban schools, whereas top performing regions demonstrate the largest gap between rural and urban schools. North Kazakhstan is an inspiring example, where the overall regional performance is high and the gap between urban and rural schools is one of the smallest.

Another alarming gap is between best and low-performing students. Take the Nazarbayev Intellectual Schools (NIS), a network of 22 highly competitive schools for the brightest students, aged 5–18. The NIS students outperform their peers by 124 PISA points, which equals to almost three years of schooling.

On functional literacy, NIS student performance is also strikingly different from the national average: according to the PISA 2018 results, only 6.2 percent of NIS students were deemed functionally illiterate compared to 64 percent nationwide. The performance of a small number of students is great and should continue to be sought, but Kazakhstan needs to raise the average level of skills both to ensure better equity, and as a question of necessity to reach the level of development to which the country aspires.

The human capital outlook

If a child born in Kazakhstan before COVID-19 was expected to fulfill just 63 percent of her or his potential, how much will the pandemic further limit their opportunities? And to what extent will these educational setbacks impact the economy’s competitiveness and productivity in the future?

The HCI value captures how productive a child will be in the future if fully healthy and educated. Between 2010 and 2020, Kazakhstan’s HCI enjoyed some, albeit mild, growth from 59 to 63 points. The increase was mainly due to improvements on the health side of the index: an increase in the adult survival rate and a decline in stunting among children under five.

Because years and quality of schooling are linked with ability to generate income in the future, school closure is likely to reduce the income of those affected. We estimate that, in Kazakhstan, after four months of school closures in March-June 2020, future income could be reduced by 2.9 percent, or equivalent to an overall economic loss up to $1.9 billion every year.

For a country with aspirations of joining the group of 30 most developed countries by 2050, strengthening human capital is a matter of urgency. Kazakhstan is the largest landlocked and most sparsely populated country in the world, and to generate growth it cannot rely only on natural resources or on densely populated markets.

What would it take?

Kazakhstan aims to increase education financing from the current 3.4 percent of GDP to 7 percent by 2025. This is a welcome initiative that will bring the country up to the OECD average on spending, but it is important to ensure that these investments are smart and efficient and that they benefit all children.

The projected severe impact of the current pandemic on educational outcomes requires commitment and continuous monitoring at the highest levels of government. Strengthened performance monitoring, assessments, mentoring, and accountability could help schools and teachers deliver results.

The Bank’s Education Modernization Project has a special focus on improving quality and equality, particularly for disadvantaged schools. The initial design aimed to improve both the quality and equity in primary and secondary education, particularly among rural and disadvantaged schools. Today, together with the Government of Kazakhstan, we are looking into ways to tailor the project to help tackle the specific equity concerns emanating from the COVID-19 crisis.

In particular, Kazakhstan will need to address the challenge of an increasing learning gap that has been exacerbated by school closures during the pandemic. The educational recovery program should include an in-depth assessment of this gap, as well as accelerated training for teachers, stronger outreach to students in need, implementation of an intensive tutoring program, and continuous monitoring of learning recovery.

This approach can help to effectively confront the challenge of the “four Kazakhstans” in the wake of COVID-19, by addressing the widening inequality in learning, especially among the country’s poorest and most vulnerable.

Join the Conversation