One of the most striking things I first noticed after moving to

Armenia was the importance of strong extended family networks – and the extent to which this aspect of Armenian social structure has evolved over time, transcending distance and getting ever-stronger through adversity.

This solid social network is an essential element in understanding and responding to the challenges that Armenia faces – and it can, if well-mobilized, help boost the country’s ability to reduce poverty and ensure that economic growth and prosperity are shared among all.

Every year, we in the World Bank use the excellent work done by Armenia’s National Statistics Service, together with global data available through international sources and our own Open Data vaults, to dig deeply into specific socio-economic dynamics. Recently, my colleagues Nistha Sinha, Maria Davalos, and Giorgia Demarchi synthesized results from a range of quantitative and qualitative analyses – including work done by the Caucasus Research Resource Center Armenia – that examine a serious social challenge: Armenia’s “out-of-balance” population.

Out-of-balance

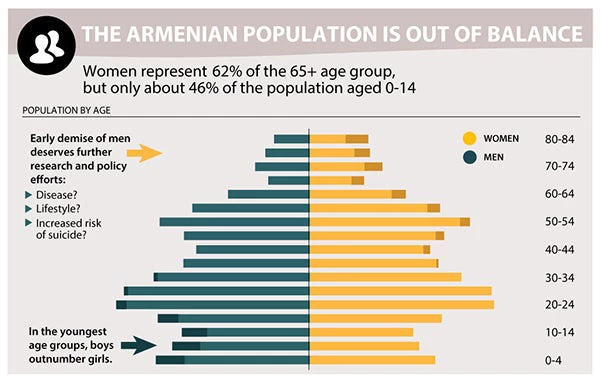

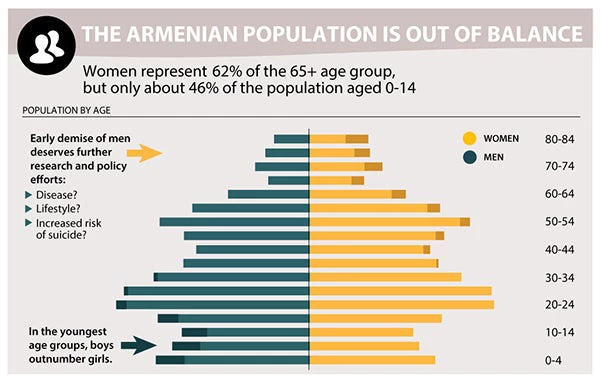

Statistics show that there are fewer older men than older women in Armenia. Not a complete surprise, if you consider that women generally have slightly longer life expectancies than men in countries across the Europe and Central Asia region. However, the difference in Armenia is quite stark – which may be caused by several factors, including greater vulnerability to life-style related diseases, as well as higher rates of suicide among older men than older women. Unfortunately, very little research or policy attention has focused on this to date.

At the other end of the age spectrum, there is another striking reality: there are fewer girls than would be expected in the earliest age cohorts. It is as if Armenia is missing girls!

Missing girls

“Missing girls” is a term originally coined by Nobel laureate Amartya Sen to refer to those girl babies that were never born due to sex selection and intervention during pregnancy. This is typically a symptom of broader gender inequalities in society, and it manifests in a stark and measurable way: a higher ratio of baby boys to baby girls relative to what would be expected in a population under normal biological circumstances. That “natural” sex ratio is generally observed to be 106.

This issue is most widely discussed with regard to two of the world’s largest countries – China and India – but it is equally stark in the three small countries of the South Caucasus. For every 100 baby girls born in Armenia, 114 are baby boys; in Azerbaijan, 116; and in Georgia, 108. In both China and India, the ratio is 117 and 111, respectively.

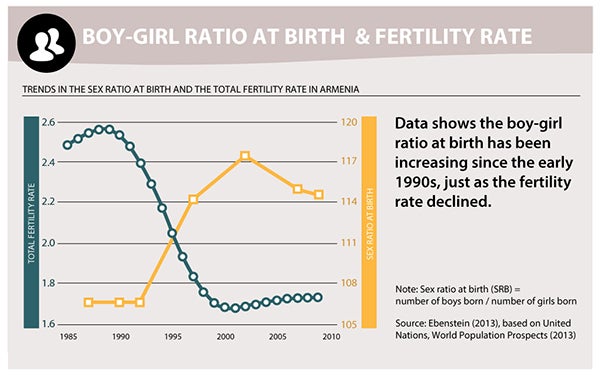

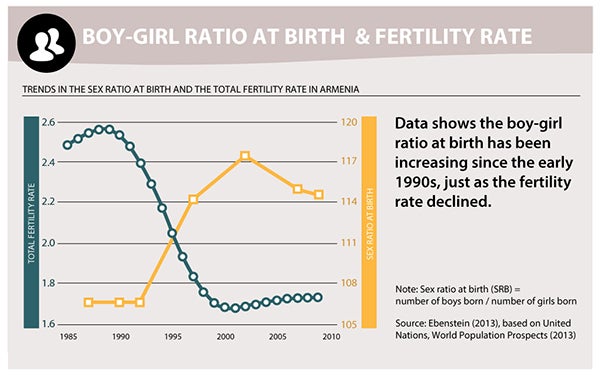

In Armenia, the sex ratio at birth has been increasing – more boys, fewer girls – since the early 1990s, just as the fertility rate declined. These two issues – skewed sex ratios, lower birth rate – taken together with steady migration of Armenians overseas, represent a complex societal challenge for the country.

Making choices in response to crises

While the social dynamics driving the low birth rate are complex, it seems likely that they are exacerbating the impact of traditional norms about the status and value of girls. Quantitative research shows that the “son preference” increases in “bad times” in countries as diverse as China and Armenia.

For example, China saw unbalanced sex ratios during internal wars, invasions, and famine occurring in the period between 1920 and 1960. In Armenia, sex ratios rose with the collapse of the Soviet Union. There is also some evidence that the 2008-2010 crisis affected fertility decisions in similar ways.

Investing in Armenia’s future

The reasons behind the “son preference” are undoubtedly complex: Armenians cite a wide range of motives, including physical and financial parental support, role as defenders of the nation, carrying on the family name, and protecting the family’s social standing.

For the Government of Armenia, the policy challenge is equally complex – since the issues are economic, historical, social, and psychological. Global experience, however, can teach policymakers a lot:

That supportive message – reinforcing the value of girls to Armenia – came on my birthday. What better present could a girl ask for?

Related:

This solid social network is an essential element in understanding and responding to the challenges that Armenia faces – and it can, if well-mobilized, help boost the country’s ability to reduce poverty and ensure that economic growth and prosperity are shared among all.

Every year, we in the World Bank use the excellent work done by Armenia’s National Statistics Service, together with global data available through international sources and our own Open Data vaults, to dig deeply into specific socio-economic dynamics. Recently, my colleagues Nistha Sinha, Maria Davalos, and Giorgia Demarchi synthesized results from a range of quantitative and qualitative analyses – including work done by the Caucasus Research Resource Center Armenia – that examine a serious social challenge: Armenia’s “out-of-balance” population.

Out-of-balance

Statistics show that there are fewer older men than older women in Armenia. Not a complete surprise, if you consider that women generally have slightly longer life expectancies than men in countries across the Europe and Central Asia region. However, the difference in Armenia is quite stark – which may be caused by several factors, including greater vulnerability to life-style related diseases, as well as higher rates of suicide among older men than older women. Unfortunately, very little research or policy attention has focused on this to date.

At the other end of the age spectrum, there is another striking reality: there are fewer girls than would be expected in the earliest age cohorts. It is as if Armenia is missing girls!

Missing girls

“Missing girls” is a term originally coined by Nobel laureate Amartya Sen to refer to those girl babies that were never born due to sex selection and intervention during pregnancy. This is typically a symptom of broader gender inequalities in society, and it manifests in a stark and measurable way: a higher ratio of baby boys to baby girls relative to what would be expected in a population under normal biological circumstances. That “natural” sex ratio is generally observed to be 106.

This issue is most widely discussed with regard to two of the world’s largest countries – China and India – but it is equally stark in the three small countries of the South Caucasus. For every 100 baby girls born in Armenia, 114 are baby boys; in Azerbaijan, 116; and in Georgia, 108. In both China and India, the ratio is 117 and 111, respectively.

In Armenia, the sex ratio at birth has been increasing – more boys, fewer girls – since the early 1990s, just as the fertility rate declined. These two issues – skewed sex ratios, lower birth rate – taken together with steady migration of Armenians overseas, represent a complex societal challenge for the country.

Making choices in response to crises

While the social dynamics driving the low birth rate are complex, it seems likely that they are exacerbating the impact of traditional norms about the status and value of girls. Quantitative research shows that the “son preference” increases in “bad times” in countries as diverse as China and Armenia.

For example, China saw unbalanced sex ratios during internal wars, invasions, and famine occurring in the period between 1920 and 1960. In Armenia, sex ratios rose with the collapse of the Soviet Union. There is also some evidence that the 2008-2010 crisis affected fertility decisions in similar ways.

Investing in Armenia’s future

The reasons behind the “son preference” are undoubtedly complex: Armenians cite a wide range of motives, including physical and financial parental support, role as defenders of the nation, carrying on the family name, and protecting the family’s social standing.

For the Government of Armenia, the policy challenge is equally complex – since the issues are economic, historical, social, and psychological. Global experience, however, can teach policymakers a lot:

- Banning technologies that identify the sex of the fetus do not work; it poses serious and sometimes fatal consequences by driving family decisions “underground”.

- Promoting gender equality and increasing women’s economic empowerment can help – by making women more resilient to pressure.

- Providing clear information publically about reproduction can help erase wrong beliefs that bias both women and men.

- Reinforcing positive images and views of girls and their value to society can change the informal institutions that are currently based on older traditions.

That supportive message – reinforcing the value of girls to Armenia – came on my birthday. What better present could a girl ask for?

Related:

- Report: “Missing Women” in the South Caucasus: Local Perceptions and Proposed Solutions - Nora Dudwick (February 2015)

- Presentation: Missing Girls in Armenia: Causes, Consequences and Policy Options to Address Skewed Sex Ratios at Birth

- Launch of “Missing Girls in South Caucasus” – 3 March, 2015

- “More Than 100 Million Women Are Missing” – Amartya Sen (The New York Review of Books, 1990)

Join the Conversation