Young people at work.

Young people at work.

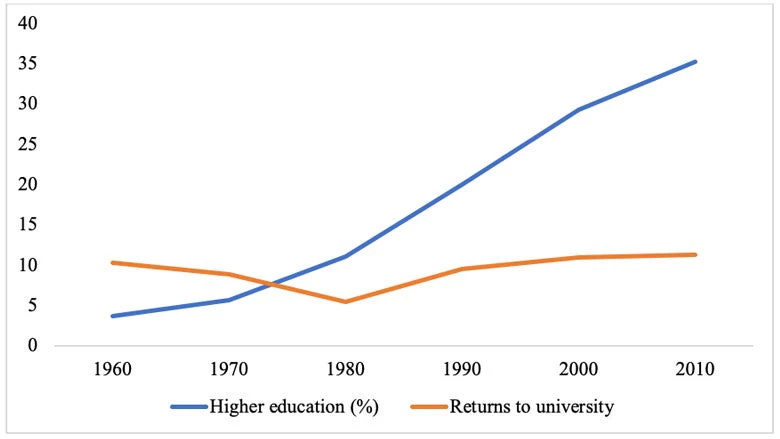

While enrollment in tertiary education worldwide has gone up three-fold since 1970, the overall returns to education – the benefits to individuals and society from investment in education – have not changed during the past 5 decades.

It was once widely believed that early investment in primary education had better labor market outcomes than later investment in secondary or even tertiary education. Evidence has since shown this is no longer the case. Since the 1980s, the private returns to higher education – which benefit the individual – have increased more than the returns to any other level of education.

Because technological change favors higher-order skills – critical thinking and cognitive ability – there has been an increase in this kind of education at lower levels of schooling. Yet most school systems are not able to keep pace with the labor market’s increasing demand for such skills. As a consequence, skill-biased technological progress is leading to greater income inequality in society.

What does this mean for countries in Europe and Central Asia? How can they ensure education outcomes keep pace with technological advancement?

Governments certainly recognize the value of education and thus spend a considerable share of state budget on education, including tertiary. In fact, expenditure on tertiary education typically accounts for as much as 22 percent of the state budget in Europe and Central Asia. Approximately 1.3 percent of the region’s GDP is spent on tertiary education.

Meanwhile, enrollment in tertiary education is increasing globally. Enrollment is highest among high-income countries, such as OECD countries. Meanwhile, the tertiary education enrollment rate for Europe and Central Asia is over 70 percent. Globally, the rate of return to education is around 8-10 percent, with the returns highest at the tertiary level, followed by primary, then secondary. This is also the case for Europe and Central Asia. Importantly, for this region, there are higher rates of return for women than for men; in fact, the highest return is achieved by women with tertiary education.

Policymakers can learn much from this. Since further expansion of university education appears very worthwhile for the individual, governments need to find ways of making financing more readily available – and in a manner that promotes equity and financial sustainability.

As economies mature and the level of schooling rises, the demands for skills change. Over time, the demand for cognitive skills – brain-based abilities we need to carry out a task and how we learn, remember and problem-solve – has increased. As has the demand for non-routine skills, while the demand for routine and less skilled jobs has declined worldwide, especially in high-income countries.

Future technological change will put an even higher premium on skills that are not easy to automate. While estimates of jobs at risk from automation vary, and while we might not know how many jobs will be lost, we do know that technology will affect many. At the same time, the number of industrial jobs are falling. This presents a significant challenge for most education systems, including in Europe and Central Asia.

Enrollment in tertiary education in Europe and Central Asia has increased seven-fold since 1960, while the returns to schooling overall remain at the same level. If nothing changes, then further expansion of the system, as is, will simply lead to greater income inequality.

Higher Education Enrollment and Returns to University Education, Europe and Central Asia

These developments have long-term implications. That’s why governments need to combat growing inequality through education quality and education finance reform. Boosting the quality of education – so that more people can qualify for tertiary education – and improving how it is financed are paramount. In some countries around the world, it turns out that the poor are in fact financing the higher education of the rich.

In terms of policy approach, governments could look towards innovative financing programs, such as income contingent loans and human capital contracts, which tap future earnings to pay for today’s education. Using future earnings to finance current education solves many of the equity issues in university finance. This way, the poor would no longer pay for the education of the rich. It would also generate more resources for education since governments in most countries face difficulty expanding quality higher education for a growing university population.

Going forward, governments in Europe and Central Asia will need to address challenges brought about by increased demand for tertiary education and higher rates of enrollment. We’ve seen that the returns to investment in education have changed over time, with greater private returns today in tertiary education.

If the supply of (quality) higher education cannot keep up with demand, however, the increasing demand for skills may produce more inequality. The bottom line is that governments in the region will need to increase efficiency, quality and equity in tertiary education, which can be achieved through better finance policy. This might decide the winner in the race between education and technology.

Since 1972, the World Bank has provided support to tertiary education development in Europe and Central Asia. Between 2000 and 2018, the Bank financed 36 tertiary education-related projects in the region, to the tune of $514 million, in addition to providing numerous analytical and advisory services.

See also: Video & Presentation – The Race between Education and Technology: Higher Education in Europe and Central Asia (September 2019)

Follow the author on Twitter: @hpatrinos

Join the Conversation