An old coal-fired power plant has been dumping vast quantities of ash out in the open for many years. Photo: Lundrim Aliu / World Bank

An old coal-fired power plant has been dumping vast quantities of ash out in the open for many years. Photo: Lundrim Aliu / World Bank

To date, climate change policy actions have primarily been considered from technical and financing perspectives. To make change happen, governance aspects also matter – institutional capabilities, accountability, as well as political economy constraints. This blog is part of a new workstream on political economy challenges and potential avenues for addressing them – with a focus on low and middle-income countries.

Due to coal’s high carbon intensity, rapidly reducing its use for power generation is critical. However, the use of coal is still growing, especially among fast-growing middle-income countries. Phasing out coal poses both economic and political-economy challenges – which need to be considered to find a path to rapid reduction.

Why coal has remained attractive for policy makers

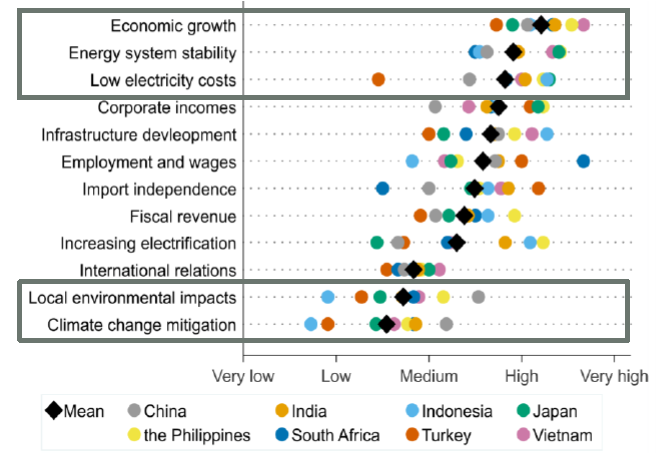

Several interlocking economic and political-economy reasons still keep coal attractive, and hinder a more rapid phasing out. First, as the authors of Steckel, Jakob et al. show in a recent book covering 15 countries, in many countries, the primary political objectives are: economic growth, energy-system stability and low electricity costs for consumers, while climate mitigation is a lower priority (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Key policy objectives in major coal investing countries

Source: Ohlendorf, N., Jakob, M., & Steckel, J. C. (2022). The political economy of coal phase-out: exploring the actors, objectives, and contextual factors shaping policies in eight major coal countries. Energy Research & Social Science, 90.

Second, despite steep cost declines, higher initial capital costs of renewable power have still been a disadvantage for economic and political economy reasons. For coal, a high share of costs accrue over a power plant’s lifetime as the fuel is bought. The opposite is true for renewables which has high initial capital costs. This matters more in middle- and low income countries (a) due to higher financing risk premia and greater challenges in mobilizing capital and (b) because power companies in many low and middle-income countries have to sell electricity at politically-set low prices. As a consequence, they are often highly indebted and struggle to raise capital for major investments themselves – while also opposing expanding private investments in renewables.

Third, research shows that political important sub-national actors have a stake in maintaining coal sectors. In regions with mines and power plants, coal is seen as fostering regional development. Jobs in the industry are often geographically concentrated, are better paid than alternative jobs, and are linked to extra benefits such as housing. Political support and votes from such regions often matter for maintaining power and hence influence national policy preferences.

Finally, coal offers business and rent-seeking opportunities along its value chain—mining, transport, distribution, and power generation. Political connections to keep these rents in place include direct representation in government or substantial contributions to electoral campaigns. In conjunction with the other factors, this proactive group of opponents to a phaseout holds considerable sway.

Changing the dynamics

So, what policy strategies could be effective at changing these dynamics, taking these political economy drivers into account?

Policy levers used in high-income countries are less likely to be sufficiently attractive or effective in middle and low-income countries. The United Kingdom has used a carbon tax to push coal out very fast. But carbon pricing requires conditions such as liberalized power markets, where costs are passed through to incentivize changes in demand. In most low and middle-income countries, power sector regulations are not market and price based, muting the impact of a carbon price on investments. Furthermore, asking low and middle-income countries start the transition by phasing out fossil fuel subsidies has remained difficult as keeping electricity prices low for consumers is a fundamental part of the social contract and of industrial policy – and as consumers often do not trust promised compensation schemes.

But there are ways of making the deployment of renewable energy politically feasible and attractive. A package of appropriate domestic reforms (in the financial and energy sectors – including sector regulations and strengthening grids) backed by international support to enable financing for investments in renewables, combined with compensating losing regions, could change political economy dynamics. Once deployed, renewables’ low operating costs make them politically attractive as they become aligned with the top policy priorities outlined above – growth, energy system stability, and low energy costs. Low operating costs can also facilitate – and support potentially be tied to - removing energy subsidies providing much needed fiscal relief.

In addition, while mobilizing financing and finding the right set of de-risking instruments poses one important challenge, we also need to stay mindful of the role of private rent-seeking interests. These are often entrenched in coal sectors - but can also emerge to capture new rents related to renewables. In both cases, they increase risks and keep energy prices higher than they could be. Therefore, a focus on supporting transparency and efforts to identify and expose rent-seeking in old and new energy sectors needs to be a second leg of international efforts at phasing out coal.

Join the Conversation