The recent Durban 2016 International AIDS Conference celebrates the success of AIDS treatment in reducing illness and death. The pall of despair and wasting death that hung over the Durban 2000 International AIDS Conference has truly been lifted. In KwaZulu-Natal, where the conference was held, AIDS treatment has increased community life expectancy by a full 11 years, reversing decades of decline -- life expectancy in KwaZulu-Natal is higher today than before the HIV epidemic. This is indubitably one of the great successes of global health.

However, the horizon is darkening, as the gathering storm grows starker. Unless we balance our celebration of the success of AIDS treatment with a sober appraisal of and rejoinder to these threats, we risk a reversal of painstaking gains.

The 2016 conference provides definitive evidence that international HIV financing has fallen from $8.6 billion in 2014 to $7.5 billion in 2015. Moreover, international financing is perilously reliant on one donor, the United States, which provides two-thirds of all international HIV financing -- broader, more diversified international and domestic financing would mitigate the risks of such concentration.

Political commitment has waned and is moving from power to symbolism. We welcome the role that princes, princesses, film and rock stars played to raise the visibility of the conference, but we wish more heads of government, senior legislators, development and finance ministers had attended.

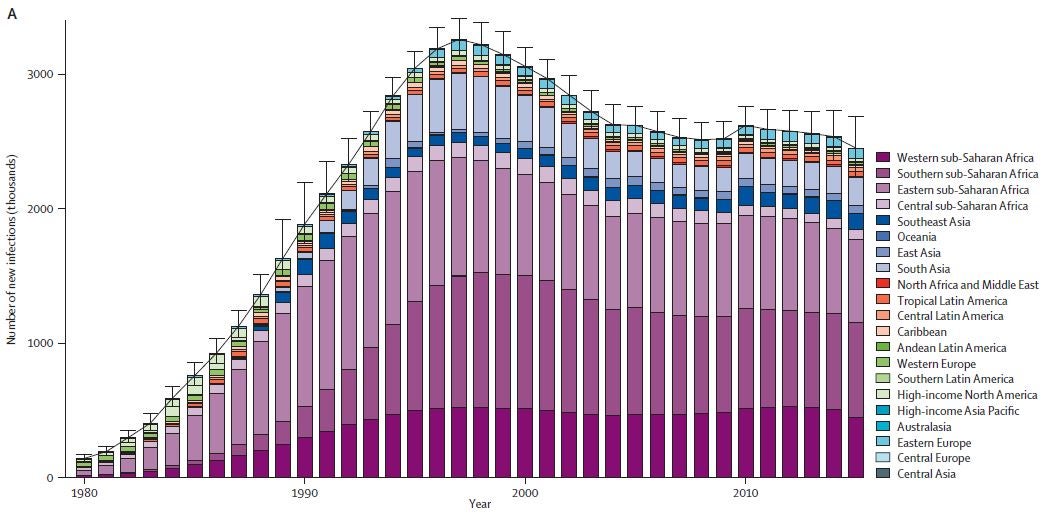

HIV incidence among adults remains tenaciously high. An independent IHME analysis shows new HIV infections leveling at 2.5 million annually - with 74 countries experiencing an increase in new infections. Even if HIV incidence were to stabilize, the absolute number of people with HIV would continue to increase, as the largest generation in history becomes exposed to the virus.

The Durban 2016 AIDS Conference marks the end of "ending the HIV epidemic" as a feasible goal with the tools we have. We need new and better tools. Talk of ending AIDS has led to a widespread perception in the broader health and development community that this crisis is over. It isn't and continued exhortations that we can end the AIDS epidemic with our existing armory may further undermine global recognition of and commitment to address this epidemic.

The 2016 conference also underscores the limitations of treatment-as-prevention (TASP - treating all for the public health benefit of reducing further transmission)) as a real world magic bullet to end this epidemic. In a cluster randomized trial in KwaZulu-Natal, TAsP did not reduce new HIV infections. In Botswana, Swaziland and South Africa, HIV incidence remains distressingly high, even as we approach or attain the ambitious 90-90-90 goal -- 90% of people with HIV knowing their status; 90% of people on sustained antiretroviral therapy; and 90% of people on therapy in viral suppression. Without decrying the transformative effects of treatment in reducing AIDS illness and death and slowing HIV transmission, we won't end this epidemic with tablets. We have never ended a global epidemic without a cure or vaccine and HIV is no exception.

We need to move beyond powerful advocacy messages to a remorseless focus on complex reality. 90-90-90 has been an effective rallying cry, but it's implied progression towards herd coverage and immunity does not capture the complexity of HIV transmission dynamics, which require us to first reach - and then retain - those with early, acute infection, high viral load and high rates of partner change or needle sharing - many of whom face multiple overlapping health and social vulnerabilities. We need a more targeted, nuanced, differentiated and comprehensive approach to epidemiological, implementation and social complexity.

What must we do better to navigate the gale winds before us?

We need to sustain international HIV financing – countries are not prepared for an abrupt transition. However, we must redouble our efforts to integrate HIV into the wider architecture of development assistance for health, an area where the Bank has a major role to play. We must focus on greater domestic financing and tackle displacement. Too many countries responded to increased global health financing by curbing domestic investment – this cannot continue. We must accelerate the progression from a short-term, emergency response to a sustained development response, where HIV is on-budget and integrated into national plans and budgets and universal health coverage (UHC) and health systems – also an area where the Bank has a key role. We need to sustain international commitment, while building national vehicles that will endure - the HIV response will be a long journey not a sprint. Ideally, international HIV support should provide the turbochargers and boosters of the global response, not the wheels and chassis.

We need to strengthen our focus on social and structural determinants of HIV transmission. Secondary education, income, greater economic opportunity and shared, inclusive growth reinforce HIV prevention – and are core Bank priorities. HIV prevention programs must also expand their focus on goals to include conjoined concerns, such as unplanned teenage pregnancies.

We must find new ways of reengaging heads of government and finance and development ministers, who may think the HIV crisis has ended and may not understand the long-term developmental and financial implications of an epidemic where new HIV infections remain stubbornly high and treatment costs rise inexorably.

We must reconceive HIV prevention - there are no good outcomes without turning off the tap of new HIV infections. We need to revitalize comprehensive prevention, including ART-based prevention, key population prevention and male circumcision in Eastern and Southern Africa, reinforced by wider education, social protection and structural interventions led by other sectors. There is no magic bullet but we do have a quiver of partially effective arrows, which if targeted, deployed and implemented at-scale together will slow new infections. As we embrace the undoubted promise of PREP, we must heed the lessons of TAsP and resist the false blandishments of a new magic bullet. We need more differentiated prevention implementation priorities that reflect HIV transmission dynamics - and concomitant implementation complexities and the realities of partial, uneven, mixed, variable and sometimes slow implementation. We also need to redouble our investment in new prevention technologies, including the vaginal ring, long-acting and implantable ARVs and above all a vaccine.

The 2016 conference was mercifully free of the gloom of 16 years ago. Yet the mood was somber and purposeful as we confront a sobering truth. Advocacy outran science and created unrealistic expectations that we have the tools to end AIDS. In reality we face a long generational fight against a dogged virus.

We must revitalize international HIV commitment and financing alongside increased domestic financing, integrate HIV in national budgets and health systems, intensify comprehensive prevention interventions and research and redouble our focus on scaled implementation, grounded in the complexity of HIV transmission dynamics and the inherent messiness of real world operational challenges.

The remarkable success of AIDS treatment continues to buy time to implement comprehensive, scaled prevention and seek the new scientific tools we need to glimpse an ultimate end to AIDS - we must seize this opportunity with renewed urgency, purpose and apprehension of the enormity of the ground still uncovered.

Join the Conversation