Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic can be applied to respond to the outbreak of the monkeypox virus. Photo: Getty Images.

Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic can be applied to respond to the outbreak of the monkeypox virus. Photo: Getty Images.

Just as we are gradually emerging from the COVID-19 pandemic, the world is facing a new global outbreak that is creating anxiety and concern around the world. Monkeypox cases are increasing worldwide and as of October, monkeypox has continued to spread to over 100 countries with more than 76,000 cases and 36 deaths.

This is also the first time that monkeypox cases have been reported concurrently in both non-endemic and endemic countries in disparate geographies. In the United States, one in five people fear getting monkeypox, but many know little about it, according to the Annenberg Public Policy Center. This combination of high emotions, lack of information, and shortages of vaccines and testing creates a difficult environment, making it hard for people to protect themselves.

Figure 1: 2022 monkeypox outbreak global map by cases

What lessons can we apply from the COVID-19 pandemic to build on successes and avoid repeating mistakes? The World Bank is supporting countries to better respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, and our research has highlighted five key factors in designing effective solutions.

- Make it easy, clear, and accessible

The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated how critical it is to have easy access to testing and to communicate clear recommendations. Complicating matters, monkeypox symptoms from this outbreak may look different compared to prior outbreaks, with less fatigue and more genital skin lesions. We also lack sufficient data on effectiveness of monkeypox vaccines and their potential side effects. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends to “be first, be right, and be credible.”

To build trust in public institutions, it is important to provide easy access to services and clear recommendations with up-to-date information in different languages, but also to acknowledge that guidelines might change as new information becomes available.

Figure 2: Examples of monkeypox communication materials

- Reduce stigma

To reduce any potential stigma related to the location, WHO renamed monkeypox virus variants from the “Congo Basin (Central African)” and “West African” strains to clade one (I) and clade two (II). Africa’s Foreign Press Association urged media outlets in Europe and North America not to use images of Africans and African descendants. As we saw with hostility toward Asians and with colloquial terms that suggested COVID-19 was a Chinese illness, terminology matters.

This outbreak is unique in that it has so far been concentrated among gay/bisexual and men who have sex with men (MSM) and has expanded to other regions. Still, anyone can get monkeypox through close contact with the infected person (or animal) or contaminated materials, such as bed linens that have been in contact with open lesions. Like the early HIV/AIDS epidemic, public health authorities face the challenge of effectively communicating to high-risk groups, while not stigmatizing them or suggesting that others are not at risk for the illness. Addressing this monkeypox outbreak among gay/bisexual and MSM is necessary from a harm reduction perspective yet must be done carefully to avoid stigma. Historically monkeypox has not been a disease associated with the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+) community, but this outbreak has taken advantage of the vulnerability of social networks.

Stigma (and dis/misinformation) can hinder effective containment, as non-stigmatized groups may not take monkeypox risks seriously and show complacency. Such stigma can also incite fear of showing the symptoms or status and lead to discrimination, marginalizing the stigmatized groups. Additionally, limited access to diagnosis and treatment has led those at risk to feel undervalued and mistreated. Consequently, it’s important to reduce stigma in communication and engagement efforts, including anonymizing procedures.

Figure 3: Social media campaign

- Targeted communication with the right messengers

From the COVID-19 pandemic, we learned that it is important to tailor communication to vulnerable communities, engaging their trusted and preferred messengers. As current monkeypox cases are concentrated among MSM, this could include partnering with organizations serving LGBTQ+ communities, LGBTQ celebrities, and the right channels (e.g., community websites, dating apps). Also, governments can bring mobile vaccination sites (e.g., mobile vaccine vans and buses) to the high-risk communities.

Figure 4: Pride cards–Learn more about monkeypox

- Address misinformation and disinformation

From the COVID-19 pandemic, we know that dis/misinformation can hinder the containment of an outbreak. Thus, it is important to proactively debunk and pre-bunk dis/misinformation. Overlapping with stigma, some people might be complacent with misinformation that monkeypox is only sexually transmitted among MSM. To address such dis/misinformation, governments and media can debunk the fake news and help people develop media and health literacy skills to discern false information.

- Prioritize targeted vaccination campaigns and ramp up disease surveillance capacity

Although countries in Africa have experienced the highest monkeypox deaths, available supplies of test kits, vaccines, and treatments are concentrated in high-income countries, making countries in Africa concerned about being left out and experiencing vaccine inequities, as they did with COVID.

Figure 5: Monkeypox vaccine access and mortality, 2022

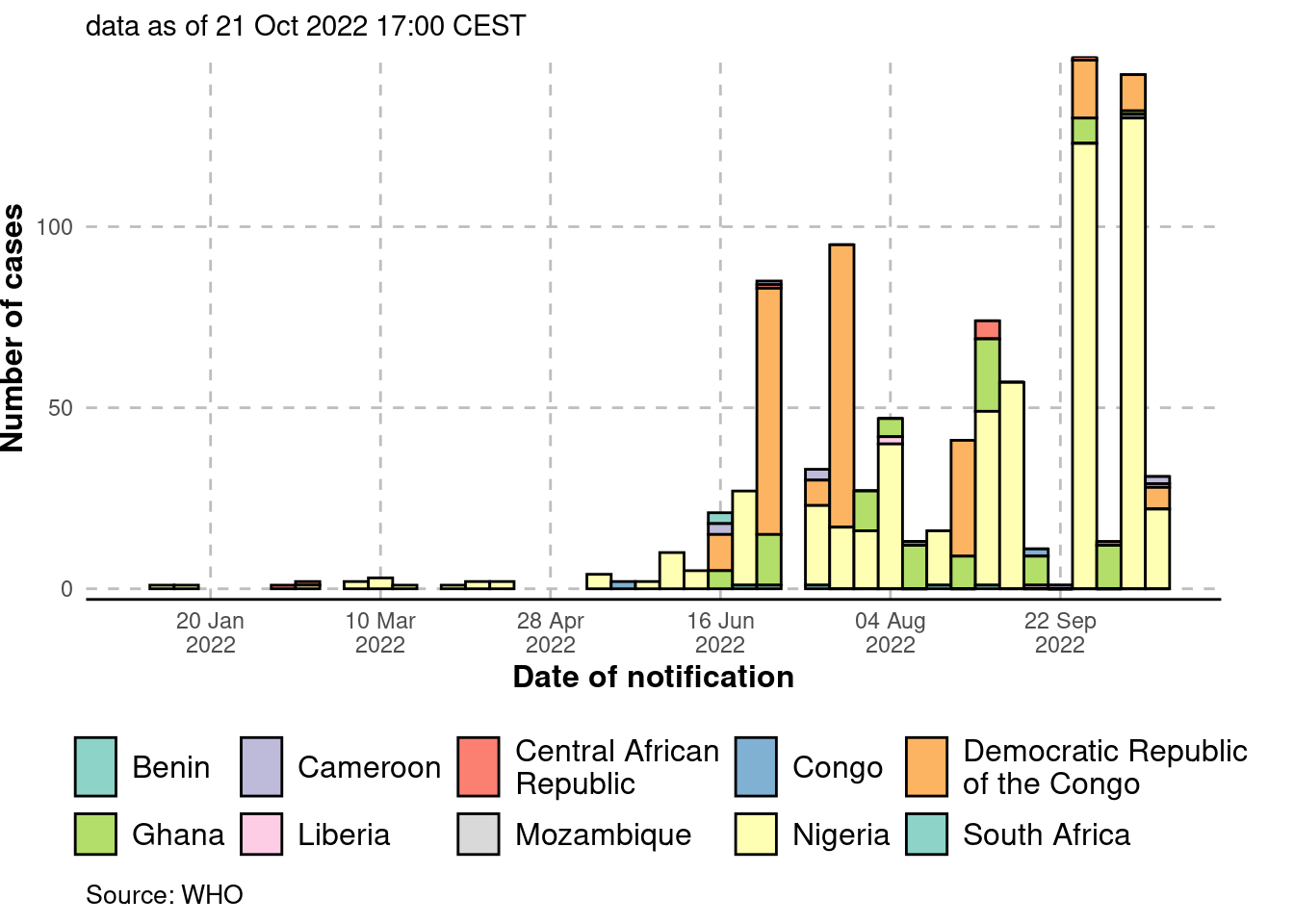

Figure 6: Epidemic curve (cases) in Africa, by date of notification

Improving access is a key concern, but mass vaccination for monkeypox will also require a clearer risk-benefit analysis for the existing vaccines and given the absence of asymptomatic transmission, we can defeat transmission much more easily than with COVID-19. Targeted approaches, such as ring vaccination campaigns, which offer vaccines to close contacts of infected patients, can help achieve the best outcomes despite limited supplies. This approach requires an efficient contact tracing system and the ability to reach specific, and in this case stigmatized, population groups. This is an additional reminder after the COVID pandemic, that countries need to invest in their disease surveillance system and their ability to detect, test, and trace. The new Financial Intermediary Fund (FIF) for Pandemic Prevention, Preparedness, and Response will provide a dedicated stream of additional, long-term financing to help strengthen these capabilities in low- and middle-income countries.

Want to learn more? Download the Bank’s interactive solutions guide for better COVID-19 policy design, and visit our website.

The work, led by the Mind, Behavior, and Development (eMBeD) unit of the Poverty and Equity Global Practice (GP), the Health, Nutrition and Population GP, and the Development Impact Evaluation Department (DIME) is supported in part by the Alliance for Advancing Health Online (AAHO), an initiative to advance public understanding of how social media and behavioral sciences can be leveraged to improve the health of communities around the world. We thank David Wilson (Program Director) and Ellen Moscoe (Behavioral Scientist) for sharing their valuable insights.

Join the Conversation