At the World Bank Group (WBG)-International Monetary Fund Annual Meetings earlier this month in Bali, Indonesia, WBG President Dr. Jim Kim posed a critical question: “What will it take to promote economic growth and help lift people out of poverty everywhere in the world…How will they reach their ambitions in an increasingly complex world?”

The key, President Kim noted, is for countries to make investments in people – ensuring that people accumulate the health, knowledge and skills needed to realize their full potential and that they can put those skills to use across the economy. In response, the WBG launched the Human Capital Project, an effort to accelerate scaled and smarter investments in people around the world, and a Human Capital Index to measure the current and potential productivity of a country’s people.

As the same time as the Bali Annual Meetings, we were in London at the Global Mental Health Ministerial Summit, hosted by the U.K. Government and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) with the support of the World Health Organization, making the case that investing in mental health is a critical but often overlooked investment in individual potential, human capital accumulation and economic success. Sadly, due to widespread global inaction, there is still limited or no access to integrated mental health services in most countries, which leaves mental health services under-resourced and creates a major problem for accessing appropriate care. Stigma and discrimination only compound the problem.

Yet this approach is myopic. A growing body of evidence shows that the social and economic losses related to unattended mental conditions, including substance use disorders, are staggering. In the world’s most advanced economies – the 36 OECD countries – mental ill health affects an estimated 20 percent of the working-age population at any time, and its direct and indirect economic costs are estimated to account for about 3.5 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), equivalent to US$1.7 billion in 2017.

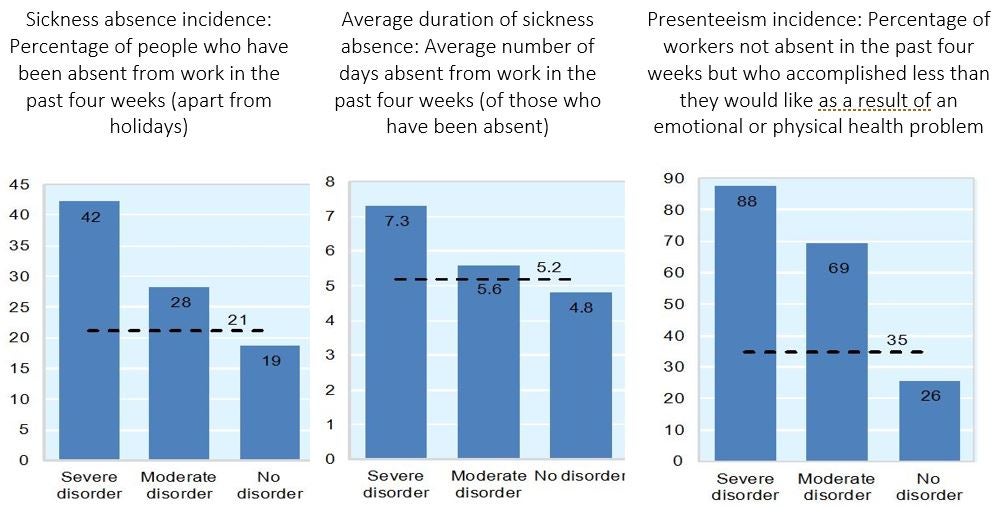

In the wealthy OECD countries, which spend on average 9 percent of GDP on health care, the high economic cost associated with mental conditions is largely driven not by mental health care expenditure, but by lost productivity in the working-age population (see Figure 1). Indeed, people suffering from mental ill health are less productive at work, are more likely to be out sick from work and when they are out sick are more likely to be absent for a longer period. Around 30 to 40 percent of all sickness and disability caseloads in OECD countries are related to mental health problems, according to a 2015 OECD report.

Figure 1: Measures of productivity loss: Sickness absence incidence and duration and proportion of workers accomplishing less than they would like because of a health problem, 2010

To effectively tackle the lost human capital from mental health conditions, it is imperative that countries turn their attention to preventing and addressing mental health conditions earlier in the life course. The economic costs of mental ill health begin before individuals enter the workforce, as mental health problems typically have their onset in childhood or adolescence, accounting for the most significant disease burden amongst children and young people. However, often there isn’t appropriate care and treatment at this life stage, or it doesn’t occur right away. This can have a lasting impact, as children and young people with mental ill health are more likely to stop full-time education early and have poorer educational outcomes (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Percentage of people who stopped full-time education before age 15, by severity of mental disorder, 2010

Source: OECD (2012), Sick on the Job? Myths and Realities about Mental Health and Work.

If countries want to improve their relative ranking in the WBG’s Human Capital Index, they must start investing seriously in integrated programs to promote mental well-being and prevent and treat mental ill health in communities, maternal and child health and nutrition programs, in schools, in their health systems, in prisons and in the workplace. It’s also value-for-money, as it is much more effective to take action while people are still in school or the workplace than wait until they have dropped out from schools, the labor market or fall into a revolving door of homelessness and incarceration.

There are examples of progress on this front. In 2015 employment and health ministers from the OECD countries signed up to show their support for an integrated policy approach, agreeing that more policies were needed to support the mental health of young people, develop an employment-oriented mental health care system, build better workplace policies with employer support mechanisms and incentives and make benefits and employment services fit for claimants with mental health problems. We need more of this. As we argued in London, an integrated, cross-sectoral approach, rather than intervention silos, is a must. Inaction on mental health cannot be a challenge for health systems to tackle alone -- communities, schools, employers and society as a whole must all be on board.

Related:

World Bank Group Global Mental Health

Mental Health in OECD Countries

Join the Conversation