What is there not to like about the Sustainable Development Goals? The 17 goals and 169 targets are nothing if not a smorgasbord of worthy ambition. But the sheer breadth and scope of the SDGs, allied to the 2030 target date, can make it difficult for governments to prioritise. It can also make it difficult for citizens to hold their governments to account. Cynics might suggest that’s why so many governments signed up for an SDG pledge that few of them have any intention of delivering.

For those of us who are more interested in achieving change than indulging in cynicism, the challenge is to identify pathways for translating rhetorical commitments into practical outcomes. If I had to select just one morsel of accountability from the SDG feast it would be this sentence tucked away in the preamble: “We wish to see the Goals and targets met…. for all segments of society. And we will endeavour to reach the furthest behind first.”

It’s tough to think of a more elevated test of fairness. The SDGs establish bold targets for eliminating extreme deprivation. But they also signal an intent to combine national progress towards those targets with ‘social convergence’, or a decline in the disparities separating the most marginalised from the rest of society. This is a marked departure from Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), which focused attention on national average progress. As the findings from an excellent 2015 paper by Adam Wagstaff and Caryn Bredenkamp noted national progress in child survival and nutrition masked widening inequalities in a majority of countries, notably in sub-Saharan Africa.

Leave No One Behind

Underpinning the SDG commitment to equity is grounded in two simple but compelling sources. The first, ethical principle. The idea that the wealth of a child’s parents, or the gender, ethnicity or race of the child, should determine life-chances in education, health or employment is an affront to basic concepts of fairness, equality of opportunity, and social justice. ‘Reaching the furthest behind first’ is a guide to public policies aimed at equalising opportunity.

The second source is rooted in more mundane arithmetic. Unless progress towards the SDG targets is more rapid among those furthest from the finishing line, the targets themselves will be unattainable.

For illustrative purposes consider the 2030 ambition of ‘ending preventable deaths’ among newborns and under-fives. On average, death rates among children in the poorest households in low-income and lower middle-income countries are twice the level for the wealthiest. It follows that, again on average, they will have to fall at twice the rate to meet the broad SDG ambition. Because child death rates and fertility rates are higher among the poorest households, this is an area in which enhanced equity has the potential to save lives. Eliminating the wealth gap in child survival between the wealthiest and poorest 20 percent in 2016 would have saved 2 million lives, according to UNICEF.

From an accountability perspective, the good news about the SDG commitment to equity is that it is susceptible in principle to measurement. The ‘in principle’ caveat is important because in practice equity has many dimensions and it can be measured on a range of metrics. Even so, the basic idea that progress for the poorest should outstrip progress for the more advantaged has the virtue of simplicity and measurability.

To stick with the child survival example, one way of approaching the measurement challenge is to track the wealth divide. The SDG target for child survival sets a minimum threshold of 25 deaths per 1,000 live births. The rate of progress required for different wealth groups to hit that target is a function of the distance they have to travel – and the poorest have to travel further and faster.

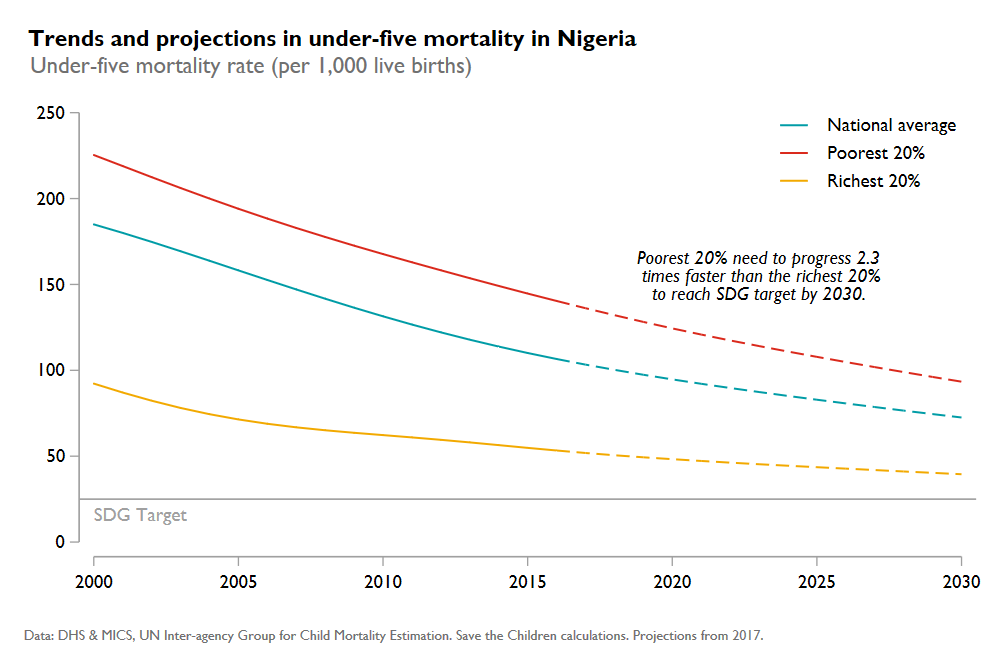

Using the SDG 2030 target as a ‘convergence point’ for Nigeria, death rates for the poorest children will need to fall at twice the rate for the wealthiest. These wealth disparities intersect with deep regional inequalities and high death rates in northern states.

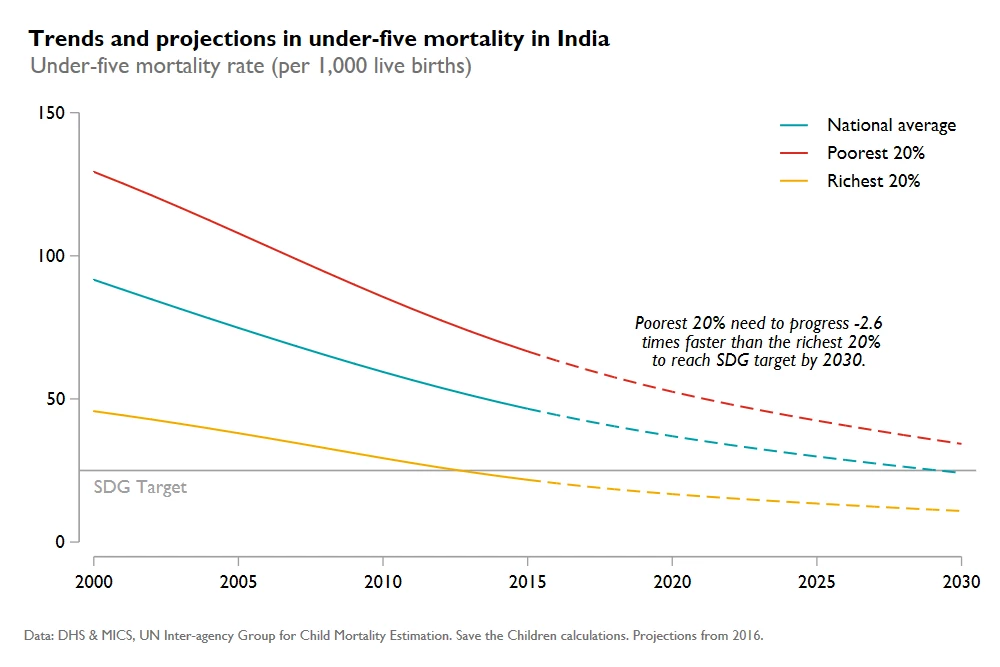

In India, the wealthiest quintile has already reached the SDG target. However, the poorest quintile is not on track for achieving the SDGs – and the death rate in this group will still be three times that of the wealthiest quintile in 2030. Put differently, in the absence of a policy-induced change in trajectory national progress will go hand-in-hand with a persistent wealth equity gap. That gap is associated with marked child mortality disparities between states. (Other country examples can be found here).

Convergence arithmetic does not provide answers to complex public policy choices – but it can turn the spotlight on underlying equity challenges. For example, Indonesia’s marked social disparities in survival are intimately related to persistently high levels of malnutrition and regional disparities in access to health care. Children from the wealthiest 10 percent are six times more likely to be born with a skilled provider in attendance and twice as likely to be fully immunised. These figures reflect not just underlying poverty, but glaring disparities in the allocation of health care resources across regions.

Monitoring Progress for the Children Furthest Behind

All the examples above use wealth as a proxy for equity, but wealth is just one dimension of inequality. In the real world, wealth disparities intersect with and magnify disadvantages associated with the rural-urban divide, gender, ethnicity, race and other markers for disadvantage. Here at Save the Children we have developed a Group-based Inequality Database (GRID) and accompanying data visualisation tools that use disaggregated data in these and other areas to help monitor progress for the furthest behind children. The GRID allows users to explore and compare inequalities between and within countries for key child development indicators – so do visit the site and explore!

Our hope is that these tools will complement others tools and data sets focused on specific thematic areas, such as the WHO Health Equity Monitor, the WB Health Equity and Financial Protection Indicators portal, and the World Inequality Database on Education. The GRID site compiles disaggregated data across a range of child health, education and protection SDG indicators, and offers new ways of cutting and visualising data. It includes a function for exploring intersecting inequalities to identify the children left furthest behind.

Our most recent addition to GRID is a tool to visualise trends over time. This can be used to create graphs, like the ones in this blog, capturing the acceleration in progress needed for the most marginalised children to reach the SDG targets. The new tool will be formally launched at the High level Political Forum in July with our forthcoming report on convergence indicators to track global and national progress towards the ‘leave no one behind’ pledge.

The point of the GRID is not just to capture different dimensions of inequality. We see it as part of an accountability toolkit that can be used by our partners and civil society groups to track the performance of their governments. There is currently far too much data reporting directed upwards from governments, UN agencies and the World Bank to global summits, and far too little transparent reporting from governments to the constituency that should figure most prominently in any accountability exercise – namely their own citizens.

Working towards the elimination of unfair inequalities in child survival is surely among the most telling of all indicators for a commitment to equity. My own view is that governments who are serious about their SDG pledges should be setting equity targets. The SDG’s 2030 target date is too remote. But a commitment to, say, halve wealth gaps in child survival over the next five years would, if backed by coherent plans of action, serve as a useful guide to policy design. It would help to focus strategies for universal health coverage and other interventions on where financial resources, skilled health workers and investments in clean water and sanitation, nutrition, and education are most needed.

We can debate specific SDG equity targets, and I would like to see the World Bank providing greater intellectual leadership in framing options. But whatever the metric, it is critically important that we translate the pledge to leave no one behind into measurable commitments against which governments can be held to account. Surely every government that signed up for the SDGs should have a plan of action setting out the pathways along which the most disadvantaged will travel to reach the 2030 goals and catch-up with the more advantaged. Without such plans the pledge to ‘leave no-one behind’ will remain less of a guide to action that delivers transformative change than a vague aspiration to be recited at high-level summits.

If the world is to get on track for achieving the SDGs, we have to be serious about combating the unfair inequalities that act as a brake on social progress. Measuring and monitoring convergence is not a panacea for these inequalities and the power relationships that sustain them. But it’s an important first step – and it's time we took it.

Join the Conversation