A majority of them answered that, being a private, for profit clinic, it must be located in major urban area since only public and non-profit health facilities can be found in the rural areas of low-income countries. But in fact, the clinic is located in the rural locality of Bamba (85% poverty rate), several hours by road from the nearest city.

Joseph Karisa, who owns and operates the clinic, is a Registered Nurse who worked for the public health service in the city of Mombasa for many years before retiring to his home village to start his private practice. Joseph and the Bamba Medical Clinic are part of the emerging trend towards Micro-Health Markets we describe in a recently published World Bank Group policy note .

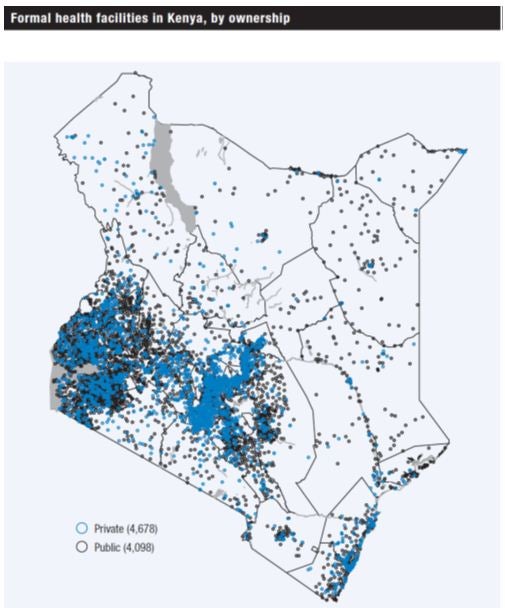

Private health facilities are more pervasive than one might think. In the map below, each circle represents registered health care facilities in Kenya as of 2011. The blue circles are private facilities; the black circles are public. More than half the registered health facilities (4,678 out of 8,776 in the country) are private, ranging from small, one- to two-person clinics to large, integrated service providers. But although private facilities are more likely to be located in areas with higher population density and higher wealth (remote arid regions in the North and Northeast are primarily served by public facilities), they are by no means found only in urban areas.

Further, the data show only those facilities registered by the government and therefore almost certainly underestimate the number of private micro-health providers. According to one estimate, about one-third of health care in Kenya, as measured by “health care interactions” or visits, is delivered by informal providers.

Kenya is not exceptional. In many low-income countries, the private sector is a dominant source of primary curative care -- the health system’s first interaction with an ill person.

Between 1990 and 2013, across 224 surveys in 77 countries, half the population sought care in the private sector. Between 1998 and 2013, even among the poorest 40% of the population, two-fifths sought care in the private sector (Karen Grepin, forthcoming). For adult and childhood illnesses combined, private sector use in the early 2000s (the latest data on adults!) ranged from 25% in sub-Saharan Africa to 63% in South Asia.

While the availability of multiple providers -- even in rural villages, in countries as diverse as Kenya, India and Cambodia -- is good news in terms of access, when it comes to the quality and safety of these services, there is bad and good news.

The bad news is that the overall quality of primary care across public and private providers is highly variable and often, quite low. Research on India and preliminary results from our own work in Kenya suggest that consultation times vary from as little as 1.5 minutes (public sector, urban India) ( 2007) to 8 minutes (private sector, urban Kenya). Providers ask on average between three and five questions and perform between one and three routine examinations, such as checking temperature, pulse, and blood pressure.

In rural and urban India, important conditions are treated correctly less than 50% of the time; when patients receive a diagnosis, it is correct less than 15% of the time. Unnecessary and even harmful treatments are widely used by all providers and in all sectors, and potentially lifesaving treatments, such as oral rehydration therapy in children with diarrhea, are used in less than one-third of interactions with highly qualified providers ( 2015). Less than 5% of patients receive only the correct treatment when they visit a provider.

As we argued in a recent article, this kind of evidence shows that, in many countries, the debate should be less about private versus public and more about quality, irrespective of the sector.

The good news is that large improvements in quality can result from changing the level of effort that providers exert in their interactions with patients. Effort, in turn, is sensitive to interventions that change the financial, non-financial, and intrinsic incentives that providers face. For example, a doctor working in his private clinic in Madhya Pradesh is 23 percentage points more likely to give the right treatment for unstable angina than the same doctor working in his public clinic.

The clear financial incentive for greater effort represented by working in a fee-for-service model rather than for a fixed salary is only one way to achieve better outcomes. Similar results can be obtained by improving community or administrative accountability, or even by playing on the intrinsic motivation of health care providers. For instance, recent research shows that effort levels can be improved through better peer monitoring, gift giving or increasing providers’ pride in their own work.

In sum, as we embark in the final push to achieve the Millennium Development Goals and set our sights on the achievement of universal health coverage, improving the quality of primary care has to become paramount. This requires both a comprehensive view of health systems that cuts across all types of providers (public, private for-profit, NGO, faith-based) and a broad set of policy interventions from smart regulations and strategic purchasing of services to supportive measures and institutional responses that can influence consumer and provider behavior.

What will be key in this effort is to keep it small: Poor people seek most of their care from smaller private and public providers, and it is here that our focus must lie.

Follow the World Bank Health team on Twitter: @WBG_Health

Join the Conversation