To prepare for and respond to shocks and emergencies, countries need more resilient primary health care systems. Photo: Flickr/World Bank

To prepare for and respond to shocks and emergencies, countries need more resilient primary health care systems. Photo: Flickr/World Bank

The COVID-19 pandemic has been a litmus test for health systems around the world. While some systems mounted strong pandemic responses, others were simply overwhelmed. One has only to look at the numbers to see the impact: more than half-a-billion COVID-19 cases and 6.2 million deaths worldwide, with the numbers going up every day.

To prepare for future shocks and emergencies and respond robustly when they occur, the world needs more resilient primary health care systems, which are at the heart of emergency response . Resilient systems can contain a health emergency, thus reducing the human and economic costs.

How do we strengthen health systems so they can be more effective when the next disaster strikes?

The first step is robust measurement, which allows policymakers and public health officials to identify strengths and weaknesses within the system that can be addressed to improve preparedness and prevention. It is the foundation upon which we can build accountability and improve overall health outcomes. A key part of this effort is to take stock of health facilities’ existing capacity to respond during emergencies while maintaining essential routine care.

The World Bank’s Service Delivery Indicators (SDI) health team has a revamped tool to do just that.

Identifying key gaps in measurement

Before the pandemic struck in late 2019, no large-scale health facility surveys used by developing countries systematically and comprehensively collected information about emergency preparedness and resilience of the entire health system.

To help health systems ensure the best outcomes for COVID-19 patients, the global health community reviewed data from previous large-scale surveys, which provided important, actionable evidence for a more robust response. For example, USAID’s Service Provision Assessment and the World Bank’s Service Delivery Indicators surveys revealed a lack of basic infection prevention materials and personal protective equipment in health facilities globally.

The investigations also highlighted significant measurement gaps. For example, these surveys uncovered little information about backup human resources for surge capacity, disinfection practices, ambulance dispatch systems, emergency communications plans, or strategies to distribute stockpiled medicine and supplies and finally also to manage excess mortality.

What’s more, public health guidelines, recommendations, and checklists on pandemic and emergency preparedness, including those adopted for COVID-19, often recommend key indicators that are essential for comprehensive preparedness and response without providing guidance on how to measure them, especially at the facility level.

The World Bank’s innovative, revamped Service Delivery Indicators health measurement tool seeks to change all that.

Innovating at scale

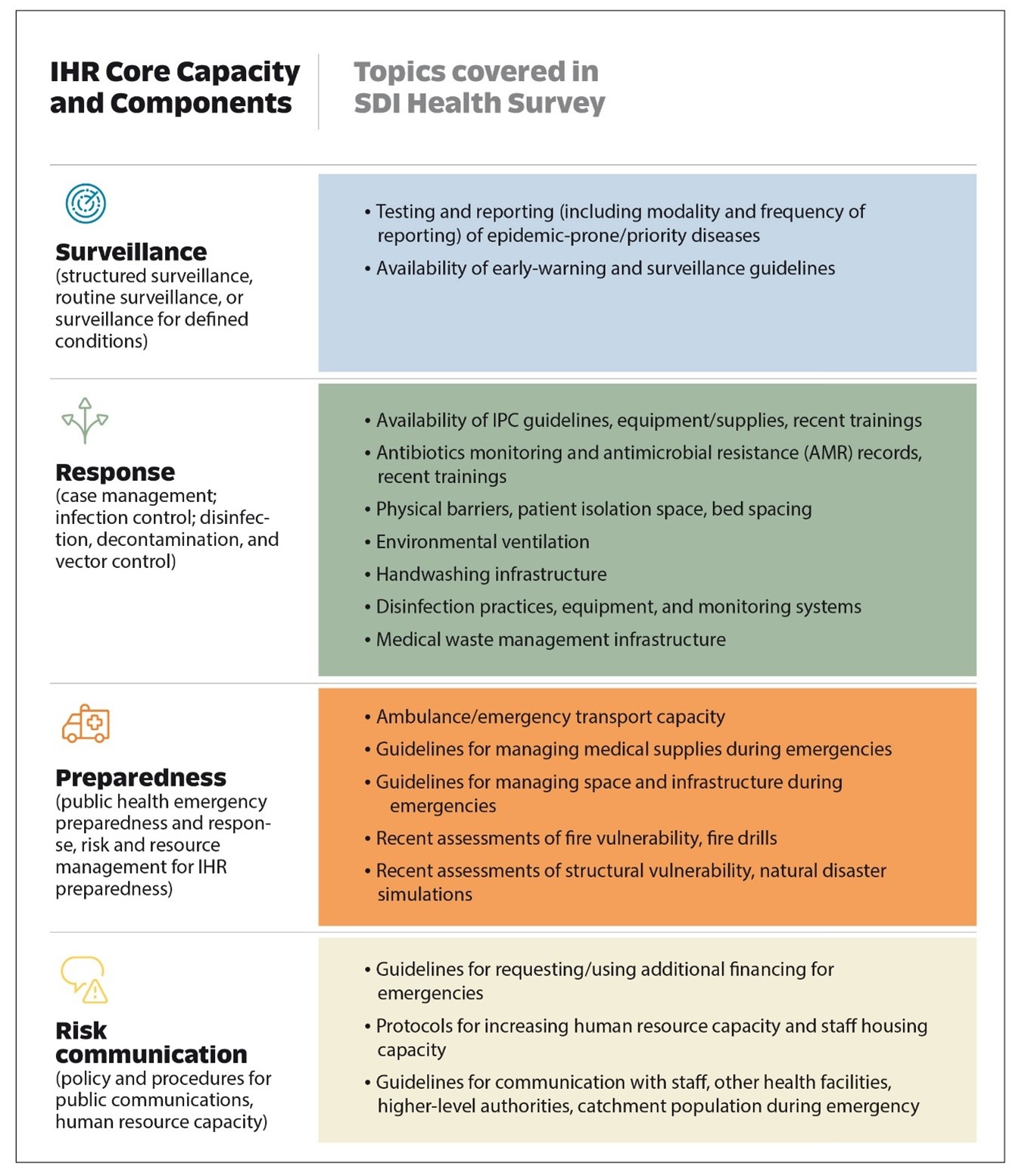

To revamp the survey, the SDI health team mapped the landscape of international guidelines, recommendations, and checklists relevant at the facility level. We honed in on the widely used International Health Regulations (IHR) Core Capacities of Surveillance, Response, Preparedness, and Risk Communication and identified common domains from other sources, including the Joint External Evaluation (JEE), Global Health Security Index (GHSI), State Party Self-Assessment Annual Reporting (SPAR) Tool, and the WHO Pandemic Influenza Checklist (Table 1).

Next, we reviewed the literature to determine best practices in measuring each Component of Core Capacity at the facility level, including extensive literature on infection prevention and control (IPC) measures, guidelines on preventing antimicrobial resistance (including facility-level measures), recommendations on managing patient surge (including optimal bed utilization), and environmental ventilation and its performance assessment.

Table 1: IHR Core Capacities and associated components relevant for assessment at the health facility level and topics covered in the SDI Health Survey

Now, to assess preparedness, with the revised survey in hand, SDI interviewers visiting health facilities ask such questions as “In the last two years, has this facility conducted any drills/simulations on managing surge capacity?” and are there “separate waiting area(s) for patients with fever, respiratory symptoms, or other symptoms of contagious diseases….?”

By incorporating measurement of health system resilience and emergency preparedness and response as a core part of facility assessment and service delivery, large-scale surveys such as the SDI can advance a more comprehensive measurement agenda.

Learning lessons to inform the future

Along with highlighting the urgent need for resilient, sustainable health systems that can simultaneously respond to acute shocks and continue essential health services—and for better measurements of these systems—COVID-19 has taught us two additional valuable lessons:

- The distinction between health security and health system strengthening is an artificial one. We need to break down the silos that exist between the two and recognize that health security is an essential aspect of system strengthening.

- Primary health care systems are key in pandemic response and management and foundational for creating better health outcomes—and they must be improved.

These lessons are critical not only to prepare for future pandemics and other shocks caused by climate change and conflict but also to support green, resilient and inclusive development (GRID).

The SDI health survey, which is now being piloted in Moldova, Armenia, and Bhutan, incorporates these lessons, and puts the global health community on a path to greater resilience and strength.

We believe that our innovative new tool will spark a sea change that will make pandemic preparedness and resilience assessment part of routine data collection. If we can identify and address gaps before the next pandemic strikes, imagine how much better prepared the world will be than it was during COVID-19.

The authors are grateful for excellent analytical contributions from Mamata Ghimire, for editorial support from Karen Schneider, and for funding from the Government of Japan.

Join the Conversation