To say that working to achieve Universal Health Coverage (UHC), while also reaching the extreme poor and tracking progress is a complex endeavor is an understatement. There is a complex nexus and

Tracking universal health coverage: First global monitoring report had on its release raised a few eyebrows. The report concluded that at least 400 million people lacked access to at least one of the basic health services outlined.

The report also found that, across 37 countries, 6% of the population was tipped or pushed further into extreme poverty ($1.25/day) because they had to pay for health services out of their own pockets. When the study factored in a poverty measure of $2/day, 17% of people in these countries were impoverished, or further impoverished, by health expenses. This finding coupled with the conclusion of the recent report, Rising Africa, which found that while poverty across the continent may be lower than current estimates suggest, the number of people living in extreme poverty has grown substantially, quickly set off alarm bells. Wagstaff and Kutzin recently posted a blog on the dilemma around the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) on UHC. There are clear signals in the sector to tread cautiously. However the pundits still believe that it is possible to identify and target the poor, quantify universal health coverage and track progress towards its key goals, both in terms of health services and financial protection coverage.

Social and community health insurance schemes have been introduced by several countries but most still miss the extreme poor. To avoid high inclusion and exclusion errors in extending benefits, Consumer Surveys, Means Tests, Proxy Means Test, Participatory Wealth Ranking and Geographic Targeting have been used with many highlights of their benefits and challenges.

Ghana is one of the countries who introduced social health insurance and attempted using Proxy Means Test tool for identifying the poor. Aryeetey and others observed that the cost of exempting one poor individual in Ghana under the scheme ranged from US$15.87 to US$95.44; exclusion of the poor ranged between 0% and 73%. The high cost is mainly a result of weak design, lack of effective monitoring and poor data quality and management.

Improving efficiency with smart ICT

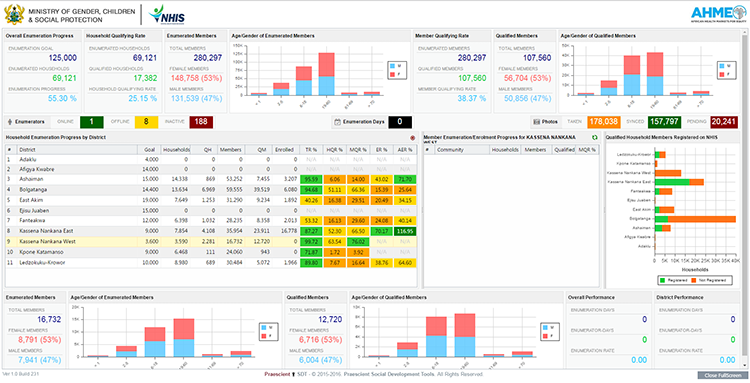

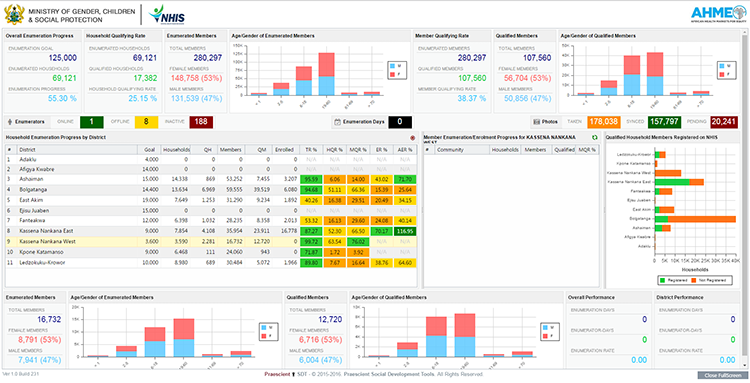

The IFC/World Bank Group Health in Africa (HIA) Initiative team have introduced technology to improve efficiency. The team has supported Ghana to deploy the proxy means test (PMT) tool onto an android tablet that works with a secure cloud-based web service to collect data - called the Survey Management and Analytic System (SMAS). SMAS tracks every enumerator in real time using the GPS on the tablets linked to google map survey data and pictures of household members and the houses are synched to a central database which populates a dashboard in real time. The system analyzes the information and sends the household PMT score back to the enumerator in micro-seconds (between 0.05 – 0.085 secs). The system uses the data received to track data errors which it feeds instantly to enumerators to be corrected, map the poverty outreach and use these figures to benchmark district poverty rates. The analysis allows technical experts to decide if the poverty outreach is high, low or within range and; segments the population base to examine how poverty intersects with geography, age, gender, and other criteria. SMAS presents all results on an interactive reporting dashboard/scorecards to display this data for management decision (see fig. 1). The tablet fitted with a mini-thermal printer instant prints receipts with household names for the qualified households only. The households are then directed to register onto the NHIS at mobile registration sites that are situated within the communities.

The system uses the data received to track data errors which it feeds instantly to enumerators to be corrected, map the poverty outreach and use these figures to benchmark district poverty rates. The analysis allows technical experts to decide if the poverty outreach is high, low or within range and; segments the population base to examine how poverty intersects with geography, age, gender, and other criteria. SMAS presents all results on an interactive reporting dashboard/scorecards to display this data for management decision (see fig. 1). The tablet fitted with a mini-thermal printer instant prints receipts with household names for the qualified households only. The households are then directed to register onto the NHIS at mobile registration sites that are situated within the communities.

So far, using this system has provided more transparent data that is easier and less costly to validate. It improves performance management, enabling fact-based decision making and provides data for planning purposes. The opportunities in dashboard/scorecard systems hold promise for tracking the Sustainable Development Goals particularly maternal and child health. We see promise in using the system to support the elimination agenda for diseases such as onchocerciasis, lymphatic filariasis and schistosomiasis among others. The GPS coordinates and phone numbers allow us to target individual households with tailored health information, monitoring and products. There is clearly an opportunity to find convergence in such innovative approaches.

The Big data challenge

SMAS seem to be resolving some essential UHC challenges– find the people, give them access to services and track progress. There is some way to go in perfecting the system. What concerns us is a different dimension. Compared to demographic surveys in Ghana this is big data! Within 100 days over 65,000 households and 270,000 persons with key demographic information and their residence coordinates have been captured in the data warehouse. By June this year that number will rise to approximately 0.5 million individuals covering about 120,000 households.

The significance of the DMAS database is amplified by the absence of frequently collected primary routine and reliable data in the Africa region. Generally the Africa Rising Report noted that Poverty rates for most African countries are imputed from surveys that are often several years old using GDP trends, raising questions about the accuracy of the estimates. On average only 3.8 consumption surveys per country were conducted in Africa between 1990 and 2014, or one every 6.1 years. The lack of consumption surveys and accessibility to the underlying data are obvious impediments to monitoring poverty.

Wendy and Adjei make clear the urgent need for improving the data available on women and children’s health. The fundamental questions are about the performance of the “suppliers” of the figures and the needs of the “clients.” Both in the Rising Africa Report and in Wendy and Adjei’s essay there is an emphasis on the significant difference between country data and global estimates and how this can impact resource allocation.

To have real time poverty data that can be promptly validated and made freely accessible should bridge the gap between country data and global estimates. Provided there is a global community of experts for the purpose of validation, this is a great opportunity. Indeed the experts must harmonize for the sake of countries and the extreme poor.

However there is a bottleneck. While the Ghana data is now available, it begs the question of data ownership, mainstreaming, accessibility and use. In most developing countries the absence of clearly spelled out data policy creates a void. Access is provided or denied on whim. This generates arbitrariness in rules governing access and use of data to advance development. The global community had not resolved this either. Data warehoused such as those once owned under the Health Matrix Network or as generated under Demographic and Health Survey are not easily available. Even if it’s some professionals in less developed countries are priced out or denied by absence of policy.

The opportunities are there and technology provides a platform to harness global modeled and country-based data to form a credible basis. What is lacking is the global policy and access framework. Put these in place and we can grow a web of global repository from different enclaves that are easily available. As the first year of the Sustainable Development Goals draws to a close the debate on the how to generate, coordinate, secure, clean and use country-based big data globally must start now.

The report also found that, across 37 countries, 6% of the population was tipped or pushed further into extreme poverty ($1.25/day) because they had to pay for health services out of their own pockets. When the study factored in a poverty measure of $2/day, 17% of people in these countries were impoverished, or further impoverished, by health expenses. This finding coupled with the conclusion of the recent report, Rising Africa, which found that while poverty across the continent may be lower than current estimates suggest, the number of people living in extreme poverty has grown substantially, quickly set off alarm bells. Wagstaff and Kutzin recently posted a blog on the dilemma around the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) on UHC. There are clear signals in the sector to tread cautiously. However the pundits still believe that it is possible to identify and target the poor, quantify universal health coverage and track progress towards its key goals, both in terms of health services and financial protection coverage.

Social and community health insurance schemes have been introduced by several countries but most still miss the extreme poor. To avoid high inclusion and exclusion errors in extending benefits, Consumer Surveys, Means Tests, Proxy Means Test, Participatory Wealth Ranking and Geographic Targeting have been used with many highlights of their benefits and challenges.

Ghana is one of the countries who introduced social health insurance and attempted using Proxy Means Test tool for identifying the poor. Aryeetey and others observed that the cost of exempting one poor individual in Ghana under the scheme ranged from US$15.87 to US$95.44; exclusion of the poor ranged between 0% and 73%. The high cost is mainly a result of weak design, lack of effective monitoring and poor data quality and management.

Improving efficiency with smart ICT

The IFC/World Bank Group Health in Africa (HIA) Initiative team have introduced technology to improve efficiency. The team has supported Ghana to deploy the proxy means test (PMT) tool onto an android tablet that works with a secure cloud-based web service to collect data - called the Survey Management and Analytic System (SMAS). SMAS tracks every enumerator in real time using the GPS on the tablets linked to google map survey data and pictures of household members and the houses are synched to a central database which populates a dashboard in real time. The system analyzes the information and sends the household PMT score back to the enumerator in micro-seconds (between 0.05 – 0.085 secs).

The system uses the data received to track data errors which it feeds instantly to enumerators to be corrected, map the poverty outreach and use these figures to benchmark district poverty rates. The analysis allows technical experts to decide if the poverty outreach is high, low or within range and; segments the population base to examine how poverty intersects with geography, age, gender, and other criteria. SMAS presents all results on an interactive reporting dashboard/scorecards to display this data for management decision (see fig. 1). The tablet fitted with a mini-thermal printer instant prints receipts with household names for the qualified households only. The households are then directed to register onto the NHIS at mobile registration sites that are situated within the communities.

The system uses the data received to track data errors which it feeds instantly to enumerators to be corrected, map the poverty outreach and use these figures to benchmark district poverty rates. The analysis allows technical experts to decide if the poverty outreach is high, low or within range and; segments the population base to examine how poverty intersects with geography, age, gender, and other criteria. SMAS presents all results on an interactive reporting dashboard/scorecards to display this data for management decision (see fig. 1). The tablet fitted with a mini-thermal printer instant prints receipts with household names for the qualified households only. The households are then directed to register onto the NHIS at mobile registration sites that are situated within the communities.

So far, using this system has provided more transparent data that is easier and less costly to validate. It improves performance management, enabling fact-based decision making and provides data for planning purposes. The opportunities in dashboard/scorecard systems hold promise for tracking the Sustainable Development Goals particularly maternal and child health. We see promise in using the system to support the elimination agenda for diseases such as onchocerciasis, lymphatic filariasis and schistosomiasis among others. The GPS coordinates and phone numbers allow us to target individual households with tailored health information, monitoring and products. There is clearly an opportunity to find convergence in such innovative approaches.

The Big data challenge

SMAS seem to be resolving some essential UHC challenges– find the people, give them access to services and track progress. There is some way to go in perfecting the system. What concerns us is a different dimension. Compared to demographic surveys in Ghana this is big data! Within 100 days over 65,000 households and 270,000 persons with key demographic information and their residence coordinates have been captured in the data warehouse. By June this year that number will rise to approximately 0.5 million individuals covering about 120,000 households.

The significance of the DMAS database is amplified by the absence of frequently collected primary routine and reliable data in the Africa region. Generally the Africa Rising Report noted that Poverty rates for most African countries are imputed from surveys that are often several years old using GDP trends, raising questions about the accuracy of the estimates. On average only 3.8 consumption surveys per country were conducted in Africa between 1990 and 2014, or one every 6.1 years. The lack of consumption surveys and accessibility to the underlying data are obvious impediments to monitoring poverty.

Wendy and Adjei make clear the urgent need for improving the data available on women and children’s health. The fundamental questions are about the performance of the “suppliers” of the figures and the needs of the “clients.” Both in the Rising Africa Report and in Wendy and Adjei’s essay there is an emphasis on the significant difference between country data and global estimates and how this can impact resource allocation.

To have real time poverty data that can be promptly validated and made freely accessible should bridge the gap between country data and global estimates. Provided there is a global community of experts for the purpose of validation, this is a great opportunity. Indeed the experts must harmonize for the sake of countries and the extreme poor.

However there is a bottleneck. While the Ghana data is now available, it begs the question of data ownership, mainstreaming, accessibility and use. In most developing countries the absence of clearly spelled out data policy creates a void. Access is provided or denied on whim. This generates arbitrariness in rules governing access and use of data to advance development. The global community had not resolved this either. Data warehoused such as those once owned under the Health Matrix Network or as generated under Demographic and Health Survey are not easily available. Even if it’s some professionals in less developed countries are priced out or denied by absence of policy.

The opportunities are there and technology provides a platform to harness global modeled and country-based data to form a credible basis. What is lacking is the global policy and access framework. Put these in place and we can grow a web of global repository from different enclaves that are easily available. As the first year of the Sustainable Development Goals draws to a close the debate on the how to generate, coordinate, secure, clean and use country-based big data globally must start now.

Join the Conversation