What’s the secret to effectively bridging the gap between research and policy? Relationships, relationships, relationships.

Last week I participated in a series of events in Nairobi: the East Africa Evidence Summit, an Agriculture in Africa event, and a policy forum with Kenya’s Vision 2030. (The full line-up of events is here; with sponsors 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6). The events included active discussions on how to more effectively bring evidence into policy. The conversations included a wide range of views, from representatives of the Kenyan and Tanzanian governments, non-government organizations, Kenyan and Ugandan academics from universities and think thanks, and researchers from outside the region. Here are a few take-aways:

Relationships mean more than just convincing the government to support Your RCT.

The successes come from ongoing relationships between policy makers and researchers. Here are some of the characteristics of those relationships:

- Hold lots of meetings with the policy makers at each stage, especially the beginning, including a range of actors within the organization, so that everyone is aware of the project, everyone knows what value the researchers are offering that the organization doesn’t already have, and everyone knows when results will be available. (Then hold more meetings when the former policy makers or NGO directors leave.)

- Be game to support the policy makers in other work. One NGO representative highlighted how the researchers had helped them look at other issues beyond their high-academic-return research project. I had this experience in the Gambia, where the government highlighted a concern about teacher knowledge, and we added a teacher content test to our endline (which ended up making the paper better anyway).

- Co-generate questions. Sometimes researchers have a great idea and just want to get a partner on board to help them implement it. But for a greater opportunity to influence policy, researchers and scientists can sit together, as Nava Ashraf has put it in the past, “to decide on the questions that have that beautiful area of overlap between something of great scientific interest and something of great policy impact.” Sometimes we may decide to trade off some of one to have more of the other, but not always.

- How do you get these relationships? If you can leverage existing relationships (i.e., you went to school with the Under-Secretary of Tissue Paper in Xanadu), then great. Or you can reach out directly. But local academics, both at universities and policy thinktanks, may have policy connections as well as local insights, and can be great partners in building quality research with policy influence.

Michael Kremer highlighted that researchers are often ignorant of the major effort required to go from a small, carefully evaluated pilot to a well implemented project at scale. (Emphasis is on well implemented, although bringing any project to scale is non-trivial.) I sometimes indulge this fantasy that if I can effectively communicate great findings to a policymaker (essentially, give an awesome presentation or design a radical policy brief), she’ll go and implement those findings at scale and we’ll both feel good. Not so easy. But there are successes. One example is deworming, going from a paper in Econometrica to the Deworm the World Initiative, reaching millions of kids in Kenya and India.

A second example is a program putting stickers inside Kenyan minivans, encouraging riders to speak up against unsafe driving. Habyarimana & Jack carried out two trials ( one, two), and now the program is being scaled up nationwide as well as tested in neighboring countries.

Two funding sources specifically for taking pilots to scale are the Global Innovation Fund and USAID’s Development Innovation Ventures.

Is it okay if not every piece of research changes the world?

I certainly hope so, given some of the research out there ( examples). But seriously, David Ameyaw from the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa made the point that some research adds to our collective knowledge rather than transforming a specific, immediate policy. Many countries that are now considering cash transfer programs are likely not basing that on a single study but on the fact that extensive evidence supports them. Christina Boswell distinguishes this “enlightenment” function (accumulated research shines a light) from the “instrumentalist” function (where a specific item of research is used to solve a specific policy problem).

It’s tempting to see this as a cop-out – an excuse to just do your research and hope in vain that it will percolate slowly into the policy world via academic journals. But it doesn’t become part of policymakers’ collective knowledge unless they know about it, and Ameyaw underlined that every piece of research they produce is presented and disseminated extensively. If your research doesn’t directly inform an upcoming policy decision, still make sure that it really gets out, so that it can be a part of future policy decisions. (This is where clever policy briefs and brilliant presentations come in.)

Ok, so that’s what some people said in panels. Is there some real evidence on this?

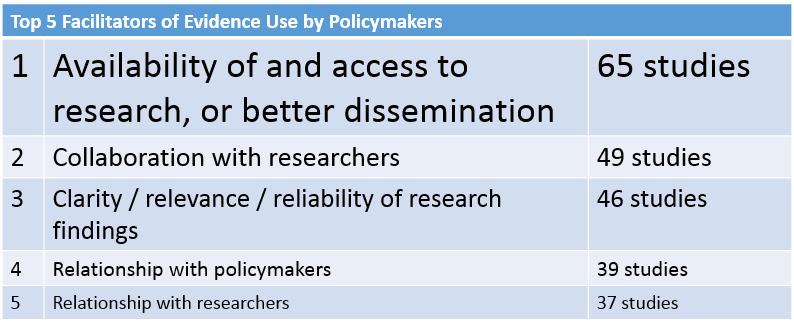

Last year, Oliver et al. published a systematic review of “barriers to and facilitators of the use of evidence by policymakers” across a range of fields. They include 145 studies from 59 countries. 33 of the studies are from low- and middle-income countries. Many of the studies are of perceptions, and many have a mixed population of policymakers, policy advisors, researchers themselves, and others.

Here are the top 5 facilitators of evidence use from their review:

Source: Minorly adapted from Oliver et al. (2014)

The similarity of #4 and #5 probably reflect the query being posed to policymakers and to researchers. Taken together, the relationship with policymakers and researchers leads the pack: “Contact, collaboration and relationships are a major facilitator of evidence use, reported in over two thirds of all studies.”

This is consistent with what came out of last week’s discussions: Relationships are key. But clarity of presentation and creating easy access to research are also important.

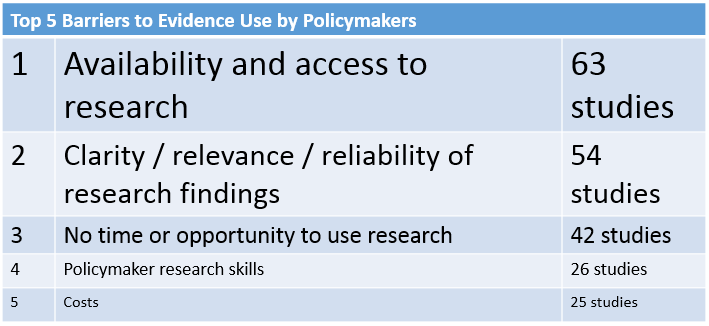

What about the barriers to research use? Below are the top 5. The first two mirror facilitating factors #1 and #3. The third barrier is consistent with the need to present research in ways that consumed clearly and quickly.

Source: Minorly adapted from Oliver et al. (2014)

The fourth barrier, policymaker research skills, reflects another point that came up in the panels last week, and it also points to what governments can do.

What’s the government’s role in all this?

Most of the discussion above puts the onus on researchers. But governments aren’t powerless in this process. Gungu Mibavu of Tanzania’s Ministry of Agriculture discussed how they have formed a policy analysis group to share research priorities with local researchers. Michael Kremer highlighted the value of governments hiring individuals with impact evaluation and research expertise, who can translate the evidence into policy. This role is like the “hinge” actors that Chioda et al. (2013) call for more of in the World Bank, people who can “communicate and operate well across different knowledge communities—academics, policy makers, practitioners.”

So…

If you’re a researcher, and you want your research to seriously affect policy and practice, then it’s time to start investing in long-term relationships that bring real value to governments and other practitioners, in addition to all those hot journal publications. The results can be transformative.

Bonus reading (i.e., mostly links to Duncan Green’s blog + commentary)

- AidData has a recent report (executive summary; report) on a survey of developing world policymakers and what reports they pay attention to. Two key findings: Studies are more likely to influence policy if they focus on a specific country (rather than a region), and prescriptive analysis tends to be more influential than descriptive analysis. Duncan Green summarizes in a blog post.

- Reed & Evely write about “How can your research have more impact? Five key principles and practical tips for effective knowledge exchange” on the LSE Impact Blog, based on their 2014 publication on knowledge exchange in environmental management. Once again: “To ensure this is useful knowledge, and has impact for those who need it, relationships must be built: two-way, long-term, trusting relationships between researchers and the people who need the new knowledge we are generating.”

- A survey of national security policymakers on what they want from international relations scholars, by Avey & Desch (2014). In that context, newspapers and classified reports were selected as the most important information sources. (Blogs fare more poorly.) Duncan Green also summarizes that one.

- Green’s do’s and don’ts on getting research into policy.

- Tseen Khoo has a nice summary of advice on The Research Whisperer.

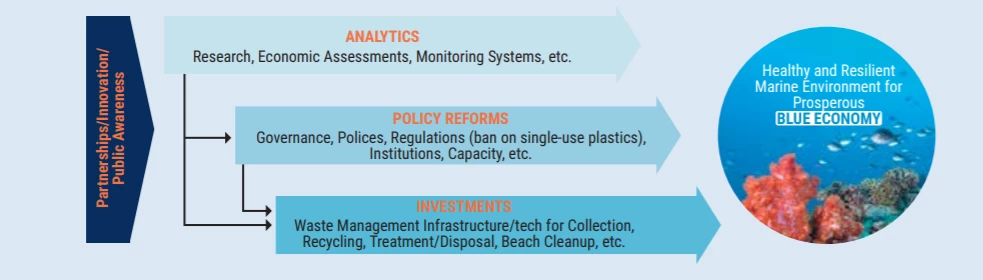

- What is the evidence on evidence-informed policy making? A 2013 report by Newman et al. Also summarized by Green. They provide a “theory of change” diagram which captures the importance of relationships but misses the value of co-generating research questions.

Source: Newman et al. (2013). Highlighting by me.

Join the Conversation