Social protection programs are increasingly designed to drive sustainable pathways out of poverty by investing targeted transfers in businesses run by poor households (Ravallion 2003). Perhaps the most comprehensive success story from such programs relates to BRAC’s Graduation program. This multifaceted intervention, including the transfer of a livestock asset, training and coaching, consumption support, access to financial services, and female empowerment, has been shown to have consistently significant (if quantitatively modest) effects in a recent six-country study (Banerjee et al. 2015), as well as continuing to confer benefits even 10 years after program implementation in India (Banerjee et al. 2021). Given the high costs and bundled nature of the Graduation program, an important next step in this research agenda is understanding which components of the bundle are necessary for generating large benefits (Sedlmayr, Shah, and Sulaiman 2020) or what other components might be added or incorporated into the next generation of these productive inclusion or adaptive social protection programs, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (Barker et al. 2021; Bossuroy et al. 2022).

But other questions do remain. The pertinent ones – the combination of which will determine the most important aspect of these programs, i.e., the profitability of the newly-formed small enterprises by the beneficiaries – I can think of are:

1. Who should programs target when trying to unleash profitable entrepreneurial activity? Haushofer et al. (2022), who find that cash transfers targeted based on deprivation (rather than, say, potential in the form of high expected conditional average treatment effects) may not be attractive for increasing social welfare – even when the social planner cares about redistribution. There is large heterogeneity in target populations across programs: for example, the target beneficiaries of NUSAF’s program to address youth unemployment (as described in Blattman, Fiala, and Martinez, 2020) are, on average, much younger, more educated, and less poor than those benefiting BRAC’s Graduation program in Bangladesh (as described by Bandiera et al., 2017), even though the basic features of the program (asset transfers, skills training, and support) are similar in both settings.

2. How should the income-generating activity (IGA) be chosen? In Graduation programs, there is a serious amount of market research done to determine the bundle of activities from which the beneficiaries can choose, although most ultra-poor household seem to get started by rearing livestock. In the second phase of Tanzania’s Social Action Funds program (TASAF II), districts had technical staff that evaluated the viability of proposed IGAs and steer groups towards opportunities with higher expected returns (although, most people proposed and received livestock assets there as well).

3. What should skills training focus on and how intense should it be? Blattman et al. (2016) found that costly supervision of microenterprises in Uganda improved business survival but did not increase consumption. Sedlmayr, Shah, and Sulaiman (2020) find, also in Uganda, that the positive effects of an integrated graduation program, which declined over time, were dampened when training and other forms of support were experimentally removed.

4. Under what circumstances, are cash transfers helpful? The evidence on the effect of unconditional cash transfers on small enterprise growth and profitability is mixed.

A new paper by Baird et al. (2022) provides experimental evidence on some of these questions. Studying a group business development program implemented by the Tanzanian government between 2008-2012 (and has been substantially redesigned since), on top of which the study cross-randomized business skills training and unanticipated, lump-sum, unconditional cash transfers (UCTs), the paper paints a bleak picture of what happens when the average small enterprise that is formed is not profitable: piling investments into an entrepreneurial activity that yields disappointing returns.

The study is a randomized evaluation of the Vulnerable Groups component of TASAF II, a program through which groups of approximately 15 individuals from vulnerable households propose a joint business plan and are provided with a large grant of working capital (approximately $6,500) to execute the plan. [1] Like the Graduation program, most of these enterprises involve the rearing of livestock such as cows, goats, and pigs. Over the top of this program, two additional interventions were randomly assigned: The first is a multi-day business skills and group trust-building training, executed around the time of receipt of the funding and randomized at the group level, following the ILO’s Start Your Business and Improve Your Business training modules. The second is an individually randomized UCT, randomly varied between $50 and $350. This combination of an asset transfer, entrepreneurial training, and individual income support replicates some but not all the features of the Graduation program, and the separate randomization of each component allows the study to unbundle their independent impacts.

In the end, none of the interventions included in the study, and indeed no combination of them, proves to have a strong effect on beneficiary welfare even in the short term

This was not because the plans were not followed:

The TASAF groups were formed, investments made, and business activities diligently operated just as was intended. The groups themselves as well as the assets that they held proved remarkably durable, at least for the 36-month follow-up period of the study, with group members not only devoting substantial time but also their own financial resources into the operation of these groups. The figure below shows that the total stock value of enterprise assets plus working capital was approximately 96% of the disbursed grant amount 12 months into operation, before slowly declining to 45% on average at 36 months among groups in which no member received a UCT (stock values are significantly higher at endline in groups that received cash, as discussed below).

These group-operated businesses were simply not very profitable, at least not for the vulnerable population TASAF targeted and/or not without more intensive support

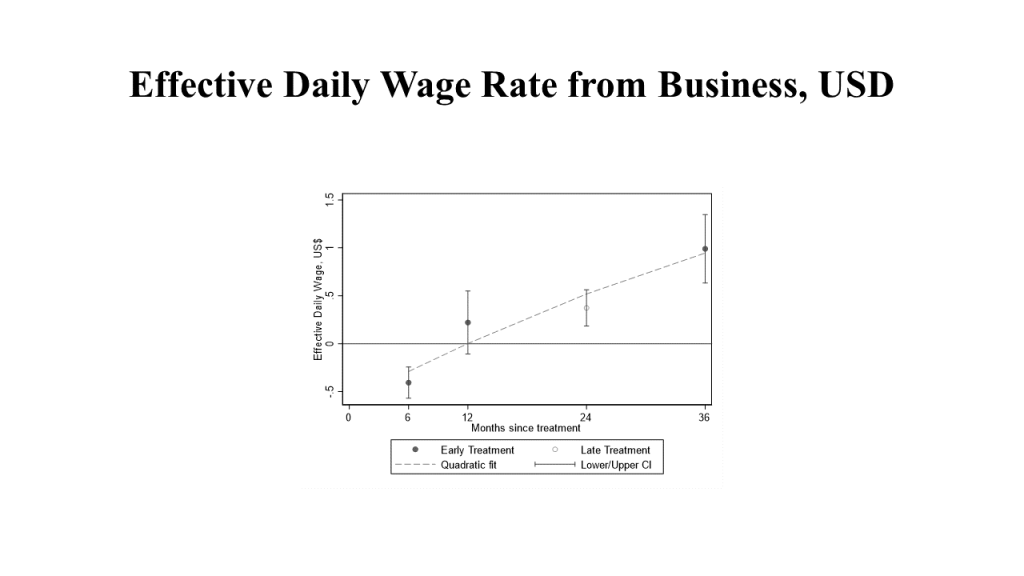

When we calculate an effective wage on the time invested in these businesses, it is close to the opportunity cost of time, and indeed lower than the food-for-work wage of $1.35 paid by the other major TASAF social protection program at the time. Wage changes over time in the UCT control are shown below – noting that these are simple group averages relative to time of disbursement, not causal impacts relative to a counterfactual – with a quadratic time trend superimposed. We see negative effective wages at six months, reflecting the fact that individual investments into the enterprises still exceeded profit taking early on). By 12 months, the daily wage is effectively zero; by 24 months it has grown to $.50 per day (using data from the Late treatment group), and by 36 months to almost exactly $1 per day, significantly different from zero.

The trainings alter the organization of the groups, empowering rank and file members (RF) and leading to some pull-back of time and contributions by group elites/leaders (GL), but do not improve business outcomes overall:

At the 36-month follow-up, a typical GL in an untrained group spends 55 hours per month working on the group enterprise and has net earnings of USD 6.91, compared with 33 hours and USD 4.31 for the average untrained RF member. These differences are statistically significant at the 95% level of confidence. However, if the groups have received training, these differences shrink substantially (even disappear) and become statistically indistinguishable: trained GL and RF members work 32 vs. 30 hours and earn USD 5.82 vs. USD 5.55 per month, respectively. The training intervention seems to have led to a more equitable distribution of the group profits between its members, i.e., reducing within-group inequality, without reducing the modest total net earnings of the enterprises. Because the training intervention explicitly highlighted aspects of collective rule-setting, transparency in the accounting of group business, and how to fairly resolve conflicts between group members (see Figure A1), it may have had the effect of empowering the RF relative to GL. However, most of the convergence comes from group leaders reducing their effort and inputs into the group enterprise in response to the training.

Most remarkably, the completely private and individual cash transfers are largely invested into the group enterprises, and indeed induce substantial additional individual investment by group members who did not receive any cash.

The table below shows that there was a strong tendency for TASAF members to invest UCTs in the group enterprises. Indeed, for every $100 received collectively by group members we find that the total value of the stock in group businesses at endline is $402 higher (over a base of $2,284). This somewhat remarkable finding indicates that the UCT provides a log-rolling opportunity through which money received by some group members effectively generates a multiplier of 4 on the stock value that groups succeed in maintaining in the joint enterprises two years later. Despite the 25% increase in total stocks arising from the UCT, however, there is no concomitant improvement either in the flow of sales or the profitability of the groups as a result of the cash transfers. In the paper (Table 10, not reproduced here), the authors show that this multiplier effect is due to significant increases in financial and labor inputs to the groups from those who receive no cash directly, and again with no improvement in profits or wages.

This set of findings amplifies a major theme of this study. These group enterprises display a remarkable collective ethos (and, perhaps, this is idiosyncratic to Tanzania), with group members working together over the course of years and sacrificing at the individual level to build a joint enterprise. The notable durability of the TASAF enterprises and the breadth of investment by GL and RF alike attest to this dedication. This collective ethos is so strong that improving the wealth of some group members with UCTs effectively exerts a tax on other group members in an effort to prevent the drawing-down of group assets that is otherwise observed. While the UCTs allow groups to protect their collective asset investment from being decapitalized, this is achieved by piling individual resources into enterprises, in which the rate of return may ultimately be too low to justify the cost.

These findings bring to mind studies such as Anagol et al. (2013), titled “Continued Existence of Cows Disproves Central Tenets of Capitalism” (The Economist article about the paper): there is little doubt that the average TASAF group enterprise failed as a capitalist entity. That paper suggests the possibility that these types of households may prefer illiquid savings and buffer stocks; have a preference for home-produced milk; low value of marginal time (the vulnerable beneficiaries certainly work only part time on these enterprises); and preference for positive skewness in returns (there are indeed a few groups that are doing fairly well – i.e., there is a distribution of returns with a very low average).

They also remind us that cash transfers are driven entirely by the way in which they are invested. When other components of an intervention have been successful in succeeding profitable business opportunities, cash is likely to achieve high returns, and where such opportunities are lacking, it will not. The coordinated work in Graduation (or Targeting the Ultra-Poor) programs – of identifying a specific opportunity that gets the beneficiary above a poverty trap threshold (Bandiera et al. 2017) and then gearing all the training, counseling, and cash transfer components of the program towards driving the profitability of that investment – appears to contain the ‘secret sauce’ of that approach.

[1] This part of the experiment uses a pipeline design among successful applications in 100 rural communities in five districts of Tanzania, taking advantage of the fact that the program did not have the capacity to fund and supervise all projects at once. A randomly drawn 50% of clusters were assigned to start their projects with a 12-month delay and form the control group for the group-enterprise intervention.

Join the Conversation