This is the first in our series of posts from graduates on the job market this year. We are still taking submissions, see the

guidelines

for details.

For some time, microfinance has been a hot topic within the development community. Many researchers and practitioners see it as a way for people to smooth their consumption over time and thus avoid the effects of bad periods. Some also think it is a good way for existing businesses to acquire the cash they need to expand their businesses. Yet, with the exception of Field, et al. (2013), who offer a repayment grace period, recent experiments have failed to find a significant effect from microfinance on business profits ( Banerjee et al. 2013, Fischer 2012, Augsburg et al. 2012, Gine and Mansuri 2011 and Angelucci, Karlan and Zinman 2013). Most studies though focus on female owned enterprises only (though Karlan and Zinman (2010) include a small number of men), and the experiments are done either at the group level or with marginal clients.

In my job market paper, I look at the relative effect of offering microfinance to both male and female business owners directly. The size of the cash grants and loans is small at $200 (500,000 USH), but common in the standard microfinance model: equal to approximately 1.5 times the monthly profits of the average business. I compare offering finance to cash grants and a control group and interact finance and grants with an ILO business training program, called Start Your Business (SYB), to see if including skills with capital can improve outcomes. I then follow the business owners to determine the effect of these interventions on both business and household outcomes over time.

I studied a total of 1,550 microenterprises representative of the types of microenterprises found across Uganda and Sub-Saharan Africa. Importantly, I selected these businesses after two baseline surveys in which the participants, both times, expressed interest in expanding their enterprises, receiving ILO trainings, and taking loans. Therefore, the businesses in this study can be directly compared to each other. They are also exactly the type of people governments and NGOs would most like to target: those motivated to expand their enterprises.

Results

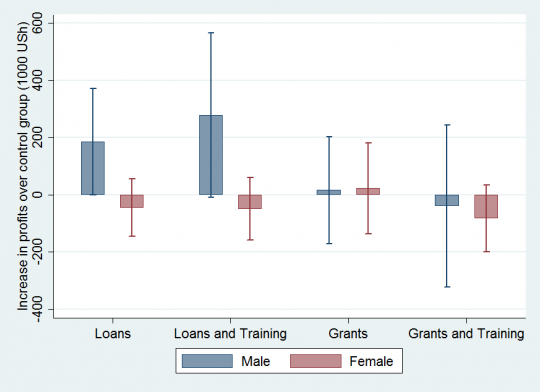

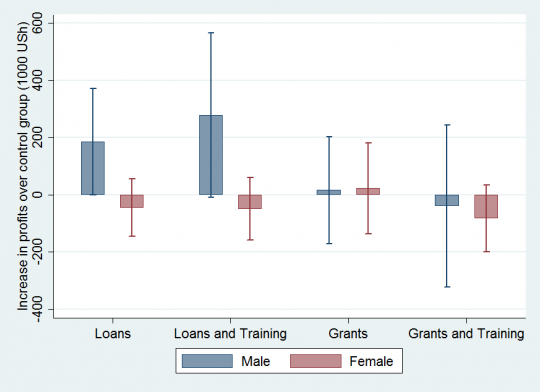

The results from the first and second follow-ups, conducted six and nine months after the interventions, are presented in Figure 1. I find that men who were offered both loans and training report 278,000 USH (54%) greater profits initially, with the effect increasing slightly over time. A heterogeneity test shows that these results are concentrated mostly among men with higher baseline profits and higher ability. I also find that men have an initial impact from the loans-only program (i.e. without being offered training) of 185,000 USH, but this effect is gone by the second follow-up. Interestingly, I find no effect from any of the grant interventions.

While the results suggest a positive (and for the literature, surprising) outcome for men, the results for women are not encouraging. I find no effects from any of the interventions during any data collection for female-owned enterprises. I also find that family pressure on women appears to have significant negative effects on business investment decisions: married women with family nearby perform worse than the control group in a number of the interventions. Women without family nearby, married or not, initially benefit from the programs, but these results are gone nine months after the programs ended.

In addition to looking at profit outcomes, I also look at other business outcomes, including effects on capital accumulation and employees. The results suggest that the effect of the loans and training for men is likely due to a combination of increased family employment and some capital accumulation. When I estimate the returns to these inputs, I find returns to capital that are similar to the larger literature on capital constraints, as well as large effects from employment, especially family employment.

Looking at broader household outcomes, I do not find effects on consumption or other household indicators, but I do find an increase in the incidence of children missing school for men with training and loans. This suggests that some family employment came at the expense of child schooling.

Some preliminary conclusions

Researchers and policy makers have struggled with how to push business to expand. This experiment presents some evidence on the value of microfinance for expanding businesses, at least for some.

The results for men are consistent with credit constraints as the loans led to large increases in business profits. That the grants did not have an effect is consistent with a control constraints problem: knowing that the loan had to be repaid appears to have led men to use the money more effectively in their businesses.

The results for women are significantly more pessimistic. None of the interventions helped the full sample of women in the short-run, and all appear to have led to a decrease in profits over time. This counter-intuitive result is due to family presence: family pressure in developing countries has long been a problem for women. Keeping cash in hand is difficult when there is pressure to spend money on school fees, health care and funerals. The evidence presented here suggests that these pressures matter for women who want to expand their businesses but have family members nearby. Men often do not face the same pressures, and, in fact, benefit from having family near to use as labor.

Counter to previous evidence on microfinance, loans have a dramatic and positive effect here, at least for men. Why might these results be so different than what has been found in the literature thus far? The most likely reason is the selection of businesses in this sample. These are business owners who have expressed an interest in growing their businesses further. Most have had loans in the past but are clearly looking for additional credit to expand their businesses. In addition, most studies have focused on women, who are the main group that microfinance organizations prefer to target due to their high repayment rates. This study includes men, and, in fact, finds that only men benefit from microfinance.

Clearly, more research is needed to better understand the constraints to business growth, especially when it comes to capital constraints and microfinance. The existing evidence from the literature suggests that female microenterprises do not grow from small interventions like the ones described here. For men, it looks like it is possible to encourage more growth, though it is unclear what the general welfare implications might be.

Nathan Fiala is a postdoctoral fellow at the German Institute for Economic Research.

For some time, microfinance has been a hot topic within the development community. Many researchers and practitioners see it as a way for people to smooth their consumption over time and thus avoid the effects of bad periods. Some also think it is a good way for existing businesses to acquire the cash they need to expand their businesses. Yet, with the exception of Field, et al. (2013), who offer a repayment grace period, recent experiments have failed to find a significant effect from microfinance on business profits ( Banerjee et al. 2013, Fischer 2012, Augsburg et al. 2012, Gine and Mansuri 2011 and Angelucci, Karlan and Zinman 2013). Most studies though focus on female owned enterprises only (though Karlan and Zinman (2010) include a small number of men), and the experiments are done either at the group level or with marginal clients.

In my job market paper, I look at the relative effect of offering microfinance to both male and female business owners directly. The size of the cash grants and loans is small at $200 (500,000 USH), but common in the standard microfinance model: equal to approximately 1.5 times the monthly profits of the average business. I compare offering finance to cash grants and a control group and interact finance and grants with an ILO business training program, called Start Your Business (SYB), to see if including skills with capital can improve outcomes. I then follow the business owners to determine the effect of these interventions on both business and household outcomes over time.

I studied a total of 1,550 microenterprises representative of the types of microenterprises found across Uganda and Sub-Saharan Africa. Importantly, I selected these businesses after two baseline surveys in which the participants, both times, expressed interest in expanding their enterprises, receiving ILO trainings, and taking loans. Therefore, the businesses in this study can be directly compared to each other. They are also exactly the type of people governments and NGOs would most like to target: those motivated to expand their enterprises.

Results

The results from the first and second follow-ups, conducted six and nine months after the interventions, are presented in Figure 1. I find that men who were offered both loans and training report 278,000 USH (54%) greater profits initially, with the effect increasing slightly over time. A heterogeneity test shows that these results are concentrated mostly among men with higher baseline profits and higher ability. I also find that men have an initial impact from the loans-only program (i.e. without being offered training) of 185,000 USH, but this effect is gone by the second follow-up. Interestingly, I find no effect from any of the grant interventions.

While the results suggest a positive (and for the literature, surprising) outcome for men, the results for women are not encouraging. I find no effects from any of the interventions during any data collection for female-owned enterprises. I also find that family pressure on women appears to have significant negative effects on business investment decisions: married women with family nearby perform worse than the control group in a number of the interventions. Women without family nearby, married or not, initially benefit from the programs, but these results are gone nine months after the programs ended.

In addition to looking at profit outcomes, I also look at other business outcomes, including effects on capital accumulation and employees. The results suggest that the effect of the loans and training for men is likely due to a combination of increased family employment and some capital accumulation. When I estimate the returns to these inputs, I find returns to capital that are similar to the larger literature on capital constraints, as well as large effects from employment, especially family employment.

Looking at broader household outcomes, I do not find effects on consumption or other household indicators, but I do find an increase in the incidence of children missing school for men with training and loans. This suggests that some family employment came at the expense of child schooling.

Some preliminary conclusions

Researchers and policy makers have struggled with how to push business to expand. This experiment presents some evidence on the value of microfinance for expanding businesses, at least for some.

The results for men are consistent with credit constraints as the loans led to large increases in business profits. That the grants did not have an effect is consistent with a control constraints problem: knowing that the loan had to be repaid appears to have led men to use the money more effectively in their businesses.

The results for women are significantly more pessimistic. None of the interventions helped the full sample of women in the short-run, and all appear to have led to a decrease in profits over time. This counter-intuitive result is due to family presence: family pressure in developing countries has long been a problem for women. Keeping cash in hand is difficult when there is pressure to spend money on school fees, health care and funerals. The evidence presented here suggests that these pressures matter for women who want to expand their businesses but have family members nearby. Men often do not face the same pressures, and, in fact, benefit from having family near to use as labor.

Counter to previous evidence on microfinance, loans have a dramatic and positive effect here, at least for men. Why might these results be so different than what has been found in the literature thus far? The most likely reason is the selection of businesses in this sample. These are business owners who have expressed an interest in growing their businesses further. Most have had loans in the past but are clearly looking for additional credit to expand their businesses. In addition, most studies have focused on women, who are the main group that microfinance organizations prefer to target due to their high repayment rates. This study includes men, and, in fact, finds that only men benefit from microfinance.

Clearly, more research is needed to better understand the constraints to business growth, especially when it comes to capital constraints and microfinance. The existing evidence from the literature suggests that female microenterprises do not grow from small interventions like the ones described here. For men, it looks like it is possible to encourage more growth, though it is unclear what the general welfare implications might be.

Nathan Fiala is a postdoctoral fellow at the German Institute for Economic Research.

Join the Conversation