- Effective adult education is difficult to accomplish all over the world.

- Quality of education is a problem across many countries in Africa at all levels (primary, secondary, tertiary, adult).

But I recently encountered some encouraging evidence on a low-cost program to improve teaching in adult education (which could have implications for other age levels). Aker and Ksoll, in a new(ish) working paper, report on an intervention in Niger in which data collection agents called teachers and students in an adult education program once a week, as a result of which test scores increased almost double relative to the adult education program by itself.

The Setting

The intervention took place in two rural regions of Niger. On adult literacy, Niger ranks the very lowest of Sub-Saharan Africa’s countries for which there are data from the last decade (which excludes only Somalia). The rural areas are probably even lower. If anywhere in Africa has room for improvement on this count, it’s Niger.

Source: World Development Indicators 2015; note that not every country is labeled, for lack of space.

The Design and the Intervention

160 villages were randomized into three groups: Adult education (70 villages), adult education + monitoring (70 villages), and control (20 villages). The small control group was based on power calculations. Control villages were to get the adult education program in 2016.

In the adult education villages, each village had two adult literacy classes (one for women; one for men). Each class met five days a week, three hours per day, over the course of four months. (Much of the rest of the year is occupied with planting and harvesting.) They were taught by community members who had been trained in the curriculum. The curriculum included basic literacy and numeracy skills, taught in the dominant local language (Hausa).

In the monitoring villages, in addition to the adult education program, data collection agents would call four people each week during the last two months of the literacy course: the literacy teacher, the village chief, one randomly selected female student, and one randomly selected male student. If someone didn’t have a phone, the phone of their neighbor was used. Agents followed a simple script, with questions like, Was the class held the previous week? How many students attended? If classes weren’t held, then why not?

The authors explain that the implementing agency (Catholic Relief Services) had an official policy of consequences for lack of attendance. However, they also highlight that in practice, there were no consequences: “no one was fired, pay was not reduced, no follow-up visits.” What’s not completely clear to me is whether the teachers believed that there might be consequences; if so, then the positive results could shift dramatically after the first year, once teachers realize that the official consequences aren’t real.

The groups look well balanced. The authors gathered test score data for literacy and math (EGRA and EGMA) as well as data on self-esteem and self-efficacy of students, and motivation and attitudes of teachers.

The Results

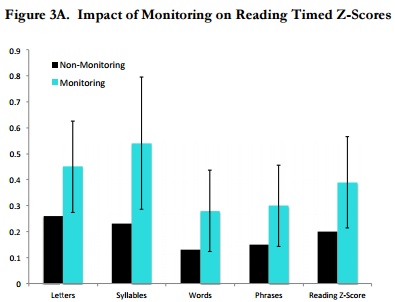

How much difference can a few phone calls make, after all? A huge difference! The figures below show the impact on literacy and math scores. Overall, the adult education intervention raised a composite reading z-score by 0.23 standard deviations, and the monitoring raised it an addition 0.18. For math, the adult education intervention increased the z-score by 0.23 standard deviations, with no significant additional impact of monitoring on the composite score but yes on three out of four tested areas.

In reading, the impact of both the adult education intervention alone and the additional impact of monitoring was biggest for the most basic skills (as in, reading letters versus reading phrases). The findings are robust both to Lee bounds to correct for attrition and to the Bonferroni corrections for multiple hypothesis testing. (Aker & Ksoll have the clearest explanation of Lee bounds I’ve ever read in another paper.)

Why did this monitoring have such a sizeable impact?

There are a few clues in the data. First, the monitoring had significant, positive impacts on teachers’ reported motivation: It could be that someone from outside the community paying attention to what they were doing motivated them to work harder. Second, the students who were called directly had much higher reading scores (0.58 standard deviations), so they may have encouraged other students. (The learning results are still significant when the directly called students are excluded, so their individual increases don’t drive the improvements.)

The authors also argue that teachers with fewer outside employment options are more responsive to the monitoring (supposedly for fear of getting fired): female teachers and also those who only have primary education were more responsive to the monitoring. More experienced teachers were also more responsive. That may be a proxy for age: older teachers may have fewer outside options. If this line of argument is true, then I’d fear that the monitoring would stop working once teachers realize that they won’t actually get fired for failing to show up. At the same time, monitored teachers aren’t significantly more likely to suspend their courses, and when they do suspend them, it’s for less time (but not much). That’s the kind of outcome I’d expect to respond to a fear of getting axed. So my money is on the impact being through increased teacher and student motivation due to increased attention.

What next?

One of the exciting elements of this intervention is that it should be easy and low-cost to replicate, both in Niger and elsewhere. At the bare minimum, one could gather phone numbers, make calls, and do the literacy and numeracy testing. The essayist Eula Biss wrote, “Most studies are not incredibly meaningful on their own, but gain or lose meaning from the work that has been done around them.” These results are promising enough to do work “around them,” both in adult education and at other levels.

Past school monitoring interventions have tended to have clear financial incentives, as in Duflo et al. (2012) in India or Cilliers et al. (2014) in Uganda; or the threat of disciplinary action (or extortion to avoid disciplinary action), as in Muralidharan et al. (2014) in India (see footnote 20). This study gives promising evidence that teachers and students may simply respond to greater attention. I’ll be excited to see updated data from Niger if and when they become available, to see if the effects endure beyond the first year, and it would be interesting to try this elsewhere.

Bonus: Alternative Titles that the Authors Might Consider If They Are Exceedingly Unwise

- Baby Don’t Forget My Number: How Calling Teachers Might Double the Effectiveness of Adult Literacy Programs

- 867-5309: Phone Calls to Schools and the Efficacy of Adult Education in Niger

- I’ll Be Calling You: Every Week. On the Phone. To Remind You That Teaching Adults Is Important

This blog post is the first in a series linked to the background research for an ongoing Africa Regional Study on Skills, led by Omar Arias and me.

Join the Conversation