- To broaden and increase the tax base

- To enable firms to access the formal economy and help spur firm growth through the potential benefits of being formal (such as access to financial services and government contracts)

- To increase the sense of rule of law by having the default be that everyone is obeying the law

- To have firms provide information about themselves to the state, which can help the government better understand the structure of the economy and to better target business programs.

The most common way of trying to achieve these aims has been through regulatory reforms that make it easier for firms to formalize. This has taken the form of “one-stop-shops” which have been implemented in at least 115 countries and which enable firms to register both as a business and as a tax entity all at once. However, a number of randomized experiments that have followed such reforms have seen very few informal firms formalize. This raises the question of whether regulatory simplification alone is not enough, and whether trying to achieve all of the above four goals with one instrument causes none of them to be attained.

Separating business and tax registration, and an experiment in Malawi

In a new working paper (replication data) (joint with Francisco Campos), we conducted an experiment with informal firms in Malawi that aimed to test whether governments can bring firms into at least part of the formal system and thereby achieve at least some of the above goals, and whether firms need additional help to realize the benefits of becoming formal.

Malawi, like much of sub-Saharan Africa, separates the process of business registration from tax registration. This separates the first reason for formalizing firms from the other three reasons. But it is then still an open question as to whether formalization without tax obligations offers meaningful benefits to firms, or whether additional policies are required.

Starting with a listing of 100 business centers in the cities of Lilongwe and Blantyre, in early 2012 we conducted a baseline survey of 3,002 informal firms, over-sampling female-owned firms so that 40% of the sample were female-owned. These firms were then separated into the following four groups:

- A control group of 757 firms

- Treatment group 1, provided free cost business registration: this group of 745 firms was offered assistance obtaining a business registration certificate at no cost, which is the main form of identification needed for opening a business bank account, registering land, and applying to government assistance programs.

- Treatment group 2, provided free cost business registration and free tax registration: this group of 293 firms was offered assistance in obtaining both the business registration certificate and a tax payer identification number, enabling us to measure the additional demand for tax formalization.

- Treatment group 3, provided free cost business registration and a bank information session: Here we focus on the idea that firms may face information problems in realizing the benefits of registration. To that end, this group of 1,207 firms received assistance in obtaining a business registration certificate, plus receives an information session with a private bank, culminating in the chance to open a business bank account.

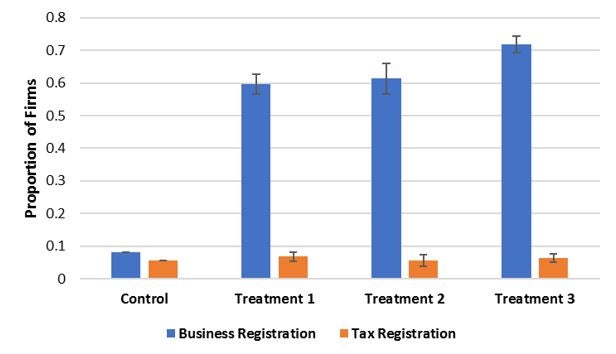

Figure 1: All three treatments increased business registration but not tax registration

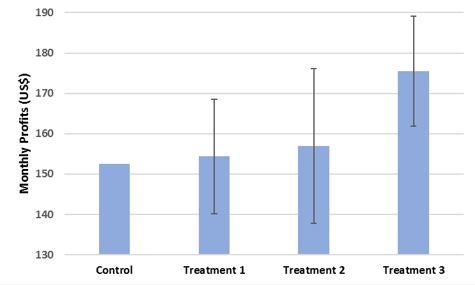

We use four follow-up survey waves that enable us to track outcomes for three years after the intervention. Survey attrition rates were 10% or lower in each wave. Neither treatment 1 nor treatment 2 lead to any measurable improvement in firm profitability (Figure 2), and relatively little change in access to finance. Only an additional 1 to 2 percent of these firms set up business bank accounts. The supposed access to finance benefit of getting a business registration certificate was therefore far from automatic. In contrast, when we added the bank information session in treatment 3 to the free cost business registration, we get a 39 percentage point increase in business bank account usage. This in turn helped the firms grow (goal 2), with sales growing 20 percent and profits 15 percent or US$27 per month (Figure 2).

Figure 2: only the combination of business registration assistance and a bank information session increased profits

Note: Treatment 3 has a significantly different impact than treatment 1 (p=0.002) and than treatment 2 (p=0.053).

This bank information session and business registration assistance was a cheap intervention to administer, averaging $27 per firm registered – which we see firms gaining in per month profits. This is thus a large increase on investment, and a substantially cheaper way of assisting firms than many other government business support programs such as training programs or business grants. Moreover, our results show that it works well for female-owned businesses as well as male-owned, in contrast to the more limited impacts of some business grant and training programs on women. But, such an intervention does require separation of the business registration from tax registration (unlike the one-stop shops), and the government does not gain at all in tax revenue over the first three years post-intervention. Efforts to increase the tax base may therefore require other interventions.

A postscript: thinking about interventions that “pay for themselves”, but don’t pay the government

Here we have an example of a policy which leads to sharp improvements in firm profits that greatly exceed the cost to the government of providing this policy. However, faced with a tight budget, the government moved to increase the cost of business registration towards the end of our intervention, and, in order to strengthen and widen the tax base, is seeking to integrate business and tax registration more. This raises a challenge for thinking about cost-effectiveness, when the costs are to the state, and the benefits to private firms. Our results show these benefits are only realized when firms are given a helping hand to both register in the first place, and then to take advantage of these benefits at banks. They therefore suggest the presence of several frictions (e.g transaction costs, information problems) that prevent firms from undertaking this profitable investment themselves. A key question for future research is to think about how to better enable firms to pay themselves for interventions that have high expected returns – and/or to help governments consider other ways of raising the funds needed to pay for such firm support.

Join the Conversation