There is a large literature that emphasizes the importance of investments made in early life for lifetime outcomes. Does growing up in a poor, conflict-afflicted country have a negative impact? There are many reasons to think yes, including the disease environment, quality of medical facilities, availability of nutrition, quality of early-childhood education facilities etc. So I was surprised by a

paper by Todd Schoellman in the most recent AEJ Macro which argues that parents, not country, are what matters for early childhood development.

His argument for why country can’t matter

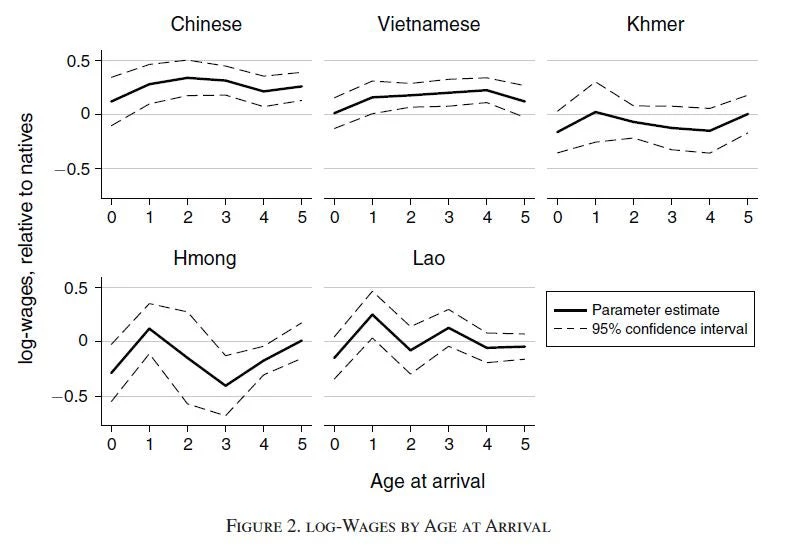

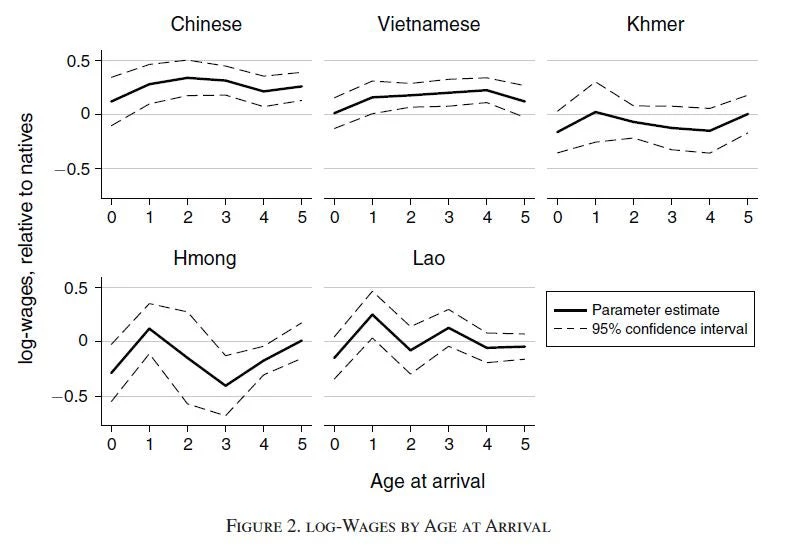

He studies the adult outcomes of refugees who immigrated to the U.S. as children, but who differed in the age of arrival. The main analysis is on IndoChinese refugees fleeing the Vietnam War and Khmer Rouge. The thought experiment is to compare the labor market outcomes and completed education of a refugee who arrived at age 1 to one who arrived at age 3 or 4. The latter had 2 or 3 more years of that critical early childhood period in a poor country (Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia) where conflict was going on, and then both come to the U.S. and grow up there. The key result is seen in this graph – which shows that adult wages are no different for those who arrived at age 4 or 5 versus those who arrive at age 0 or 1:

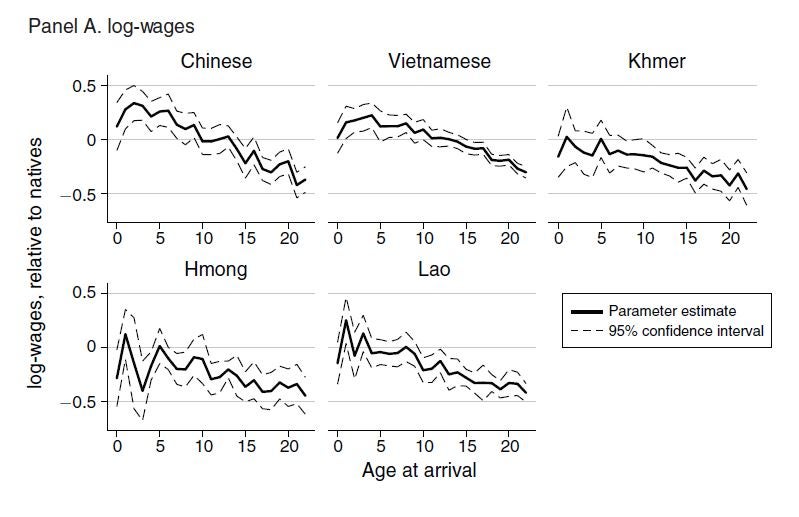

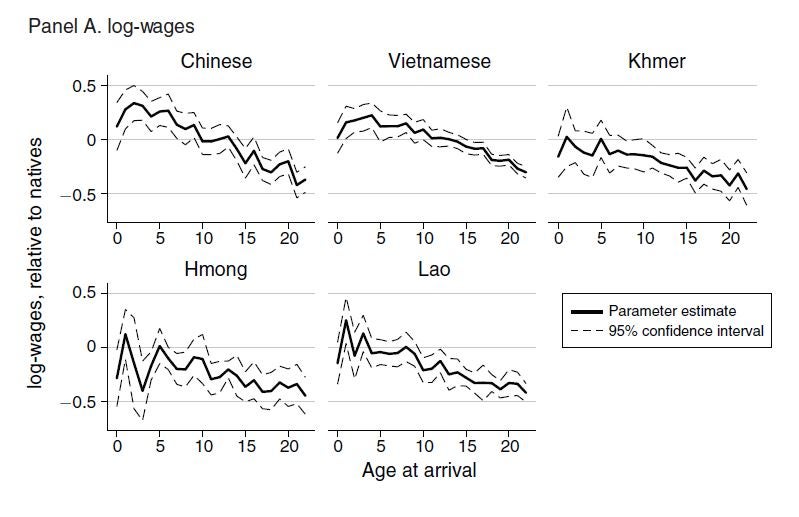

This also seems puzzling given the immigration literature on assimilation, which has emphasized that kids who arrive earlier assimilate better. This is in fact true once one goes beyond the early childhood range - refugees who arrive at age 22 have 5 to 10 fewer years of schooling and 30 to 60 percent lower wages than refugees who arrive in early childhood, as seen in this second figure which expands the age range considered from the first:

What’s going on?

Two explanations spring to mind:

If you want to argue about another type of external validity, I would argue that the U.S. may not be very good at providing early childhood care for refugees (at least at the time of the study) – this is not discussed in the paper, but it seems likely to me that the U.S. is a worse place to receive early childhood care if you are a poor family than most European countries or Australia and New Zealand – so perhaps it is only when you get into public schools here that you start to get the benefits. The type of data the authors have doesn’t tell us anything about what early childhood educational facilities, if any, were available to these refugee kids.

His argument for why country can’t matter

He studies the adult outcomes of refugees who immigrated to the U.S. as children, but who differed in the age of arrival. The main analysis is on IndoChinese refugees fleeing the Vietnam War and Khmer Rouge. The thought experiment is to compare the labor market outcomes and completed education of a refugee who arrived at age 1 to one who arrived at age 3 or 4. The latter had 2 or 3 more years of that critical early childhood period in a poor country (Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia) where conflict was going on, and then both come to the U.S. and grow up there. The key result is seen in this graph – which shows that adult wages are no different for those who arrived at age 4 or 5 versus those who arrive at age 0 or 1:

This also seems puzzling given the immigration literature on assimilation, which has emphasized that kids who arrive earlier assimilate better. This is in fact true once one goes beyond the early childhood range - refugees who arrive at age 22 have 5 to 10 fewer years of schooling and 30 to 60 percent lower wages than refugees who arrive in early childhood, as seen in this second figure which expands the age range considered from the first:

What’s going on?

Two explanations spring to mind:

- Remediation – perhaps kids are able to make up for any deficit during their time in school and growing up in the U.S.? The author rules this out by pointing to research by Heckman and co-authors that says that is relatively easy to remediate low human capital at birth but much more difficult to remediate low early childhood human capital. He also calibrates a model to show remediation is unlikely to explain this, and in a companion paper, uses other data to show no difference in educational investments by age of arrival.

- Measurement error – if refugees can’t remember well what age they were when they arrived, then this noise would make it seem like there is no relationship. He works out how bad this measurement error would have to be, and would need there to be very little signal in age of arrival to overturn the results.

If you want to argue about another type of external validity, I would argue that the U.S. may not be very good at providing early childhood care for refugees (at least at the time of the study) – this is not discussed in the paper, but it seems likely to me that the U.S. is a worse place to receive early childhood care if you are a poor family than most European countries or Australia and New Zealand – so perhaps it is only when you get into public schools here that you start to get the benefits. The type of data the authors have doesn’t tell us anything about what early childhood educational facilities, if any, were available to these refugee kids.

Join the Conversation