This is the 18th in our series of posts by PhD students on the job market

Border enforcement and risk for migrants

Migrants move in search of opportunity and, in many contexts, they try to overcome barriers to migration by entering destination countries irregularly. High-income countries implement border enforcement to deter irregular migration, but these policies impose risks on migrants trying to cross. In the Mediterranean, migrants leave North Africa on unseaworthy boats to reach Europe. Authorities intercept them to avoid shipwrecks; however, they keep rescue from occurring close to North African shores, to deter future migration. From 2014 to mid-2017, around 400,000 people left the North African coast for Italy, and 12,000 drowned before reaching rescue. Understanding the consequences and drivers of border enforcement is essential, but also extremely complex, due to the large set of actors involved in irregular migration: not only migrants and governments, but also smugglers, NGOs, and public scrutiny in host countries.

In my Job Market Paper, I leverage a novel dataset of high-frequency geo-localized data on rescue interceptions for migrants' boats leaving from Libya from 2014 to 2017 to investigate the impact of the location of rescues on migrants' safety and on migration choices. In addition, I study how policymakers' preferences and public scrutiny influence policy choices. To do so, and to produce policy counterfactuals, I estimate a dynamic model of policy choice, where policymakers act to minimize both migrants' arrivals and deaths, and where I model media and public attention. I show that reducing rescue distance increases safety, but it also increases future departures. I also find that temporary rises in attention lead policymakers to reduce the risk of shipwrecks, at the cost of increasing future departures.

Data on migrant rescues and shipwrecks

I employ a novel dataset of rescue operations during operation Triton, obtained from Frontex, the European Border and Coast Guard Agency. The dataset includes date, geolocation, and the number of migrants rescued for all the rescue operations with survivors from November 2014 to April 2017, covering a total of 2,409 operations. I aggregate these data in a weekly measure of the distance of rescue operations from the Libyan coast for the 126 weeks I consider. I complement rescues data with information about date and number of migrants involved in shipwrecks collected by the IOM Missing Migrants Project from institutional sources, media, and NGOs.

Deterrence and humanitarian concerns

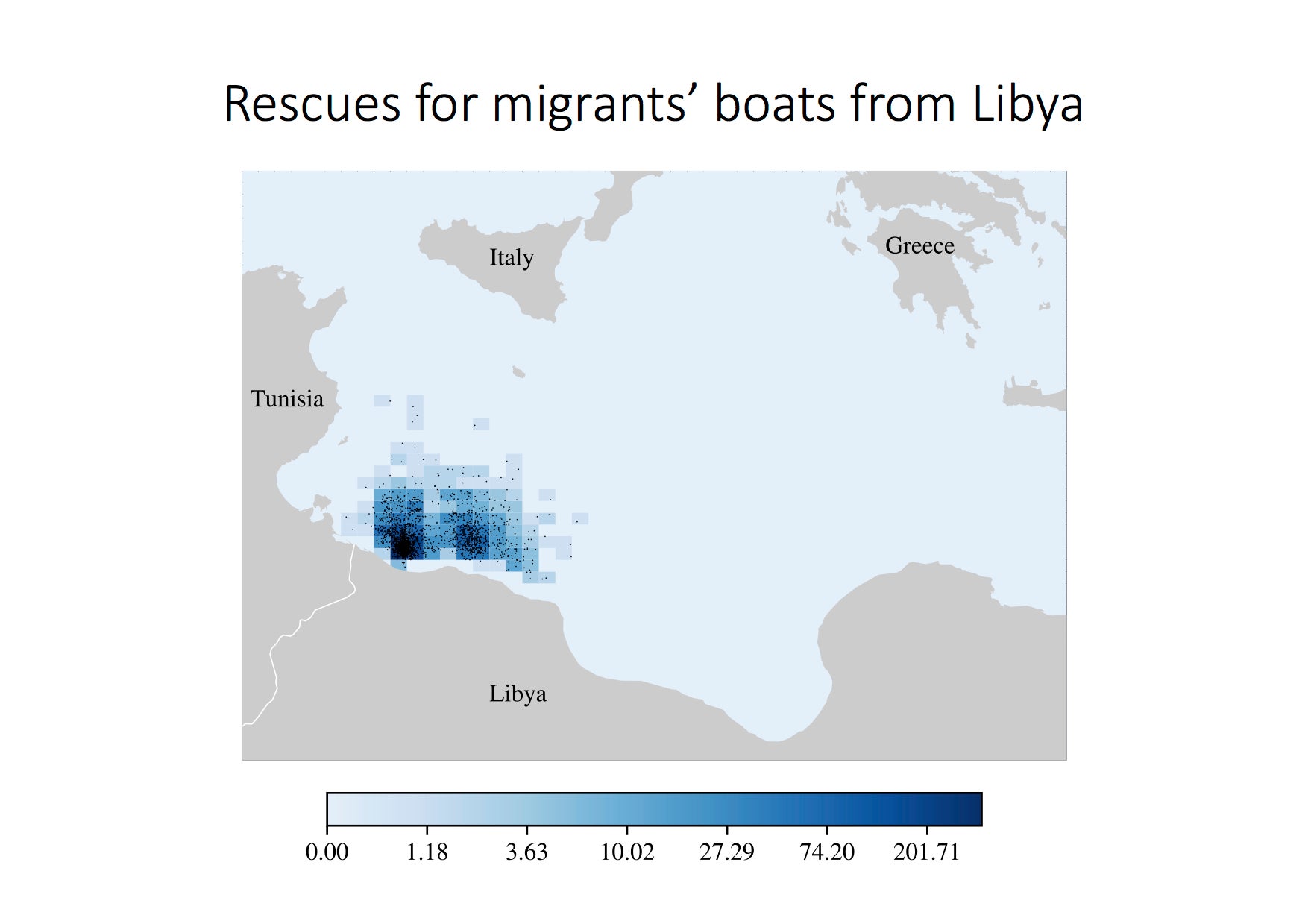

From 2014 to 2017, civil-war-torn Libya was incapable of rescuing boats in distress. Migrants' boats leaving Libya to reach Europe were rescued and brought to Italy by European coastguards, NGOs, or commercial ships. However, to discourage departures, rescue did not happen too near the Libyan coast. Figure 1 depicts rescues (dots) and rescue frequency (shaded squares). The average rescue took place around 50KM offshore, a considerable distance for migrants typically traveling in overcrowded dinghies. Between 2015 and 2017, around 2% of migrants attempting to cross lost their lives (IOM, 2020a).

Figure 1

Sea color represents the number of rescues in the sample period.

Frontex and the Italian government, the main institutional actors involved, could influence rescue distance by deciding where to conduct searches for migrant’s boats. NGOs also engaged in rescue operations in the sample period. Since they almost always represented a minority of operations, their presence did not prevent institutional actors from affecting rescue distance altogether. However, NGOs might have influenced distances set, and I consider this in the model.

To study how the location of rescue operations causally affect death risk, I introduce an instrumental variable based on commercial traffic in the Mediterranean Sea, which I proxy with the number of ships entering the Mediterranean Sea through the Suez Canal. The sea area between Western Libya and Italy is key for maritime traffic. I show that when traffic is high, rescues move closer to the Libyan coast, and interceptions by commercial ships do not increase, suggesting that European authorities wish to avoid disruptions to trade and shipping. As the overwhelming majority of ships entering the Mediterranean through Suez have to travel long distances before reaching the Canal, and because the instrument is based on lagged crossings, it is unlikely that shipping companies consider migrants’ crossings in setting their routes. Including a fine-grained set of seasonal controls, I show that the instrument is not weak under conventional F-stat levels. I do not observe counterfactual rescue distances for migrants who lost their lives in shipwrecks, but I use my model to correct the bias this creates in estimating the impact of distances on risk. I show that reducing rescue distance by 10KM reduces death probability by approximately 2 percentage points. Controlling for migrants’ departures, which might react to maritime traffic, does not affect results. Despite the completeness of Missing Migrants data, some migrants’ deaths could go undetected, especially when distances are higher; in this case, the effect estimated above would be a lower bound on the actual one.

Rescue distance also shapes migrants’ incentives to attempt crossings. Using weekly departures and rescue distance data, I find that increasing rescue distance decreases departures in the following week. According to the Italian Coast Guard (CGCCP, 2017), no migrant leaving from Libya reached Italian shores autonomously from 2015 to 2017; this reduces possible concerns about detection bias.

In sum, when setting rescue distances, policymakers face a trade-off between improving migrants’ safety and reducing future departures. To understand how they weigh these incentives and to produce policy counterfactuals, I estimate a dynamic structural model of border enforcement.

Modeling border enforcement decisions

I model policymakers as minimizing both deaths and arrivals, present and future. If their concerns were only humanitarian, they would save migrants as close as possible to the Libyan coast to prevent any risk. If they instead exclusively aimed at reducing migration, they would rescue migrants as far as possible from Libya. Rescues typically neither occur very close to Libya nor very close to Italy, suggesting that policymakers accept a certain number of arrivals to reduce deaths.

Using high-frequency data on rescues, I estimate a dynamic model where the policymaker acts to minimize arrivals and deaths, present and future, knowing that increasing safety might increase departures. I take into account factors other than policymakers’ preferences. I consider the role of good weather conditions, making it easier for migrants’ boats to leave Libya. Also, I model NGOs as non-strategic actors, prioritizing the objective of saving migrants at sea, and then operating close to Libya. More precisely, I think of NGO presence in the rescue area as reducing policymakers' ability to set high distances, thus improving safety conditions for migrants. Although I do not model NGO entry explicitly, I take into account the persistence of their presence. Simulating the model up to the steady-state, I find that the rescue distance chosen by policymakers in the model is very similar to the average one, resulting in high departures and low safety; the policymaker is unable to reduce deaths by either reducing departures or increasing safety.

Importantly, the model takes into account the role of public attention. I measure public attention using Google Trends data, cross-validated with newspaper coverage data. If public attention to migration temporarily increases, contemporaneous policy outcomes become more visible, leading policymakers to accept more future arrivals in order to reduce present deaths. My structural approach also considers the impact of policy outcomes on attention and its potentially confounding role. Figure 2 shows how rescue distance (left-hand panel) and survival probability for migrants (right-hand panel) respond to a positive attention shock, in the weeks following the shock. The dotted line represents a one-standard-deviation shock, and the solid line a two-standard-deviation one. As anticipated, increased public attention reduces the risk for migrants. Further, policy outcomes amplify this effect: lower distances induce higher departures, in turn leading policymakers to reduce distance to avoid tragedies. I also find a negative and persistent effect of past attention on rescue distance using OLS and 2SLS estimation exploiting exogenous changes in public attention caused by newsworthy sports events that crowd out attention to migration. Using OLS, I also show that the presence of NGOs in the rescue area reduces the effect of attention, suggesting they do not drive the result.

Figure 2

Weeks since attention shock on the x-axis.

Implications and Limitations

This work is the first to take a global perspective in jointly evaluating drivers and consequences of border enforcement policy, taking into account both policy incentives and consequences for migrants. In so doing, it sheds light on the fundamental trade-off between migration deterrence and humanitarian concerns. A limitation of this work is that it considers a short-term policy instrument, rescue distances. While rescue distance was arguably the only policy instrument available to authorities in the period of my analysis, relying only on such instrument leads policymakers to be stuck in a deadly equilibrium. Long-term policies building legal channels to migration could bring safety to migrants' path to opportunity.

Giacomo Battiston is a PhD student at Bocconi University (Italy).

Join the Conversation