Looking at doors at Makerere

Looking at doors at Makerere

It’s well known that in the absence of market failures or externalities, giving people cash with no strings attached (unconditional cash transfers or UCTs) is better than giving them cash conditional on certain behaviors by the beneficiary. Inefficiencies (private or social) or political economy arguments are necessary to justify attaching conditions to cash transfers in order to get households to invest in more of something that the government deems desirable. From a welfare perspective, if the households were already operating with no failures (such as imperfect information, etc.) other than credit constraints, UCTs would be sufficient to solve the problem and CCTs would inefficiently distort behavior through the condition. A new paper by Bryan et al. (2021) provides a new example of such a distortion.

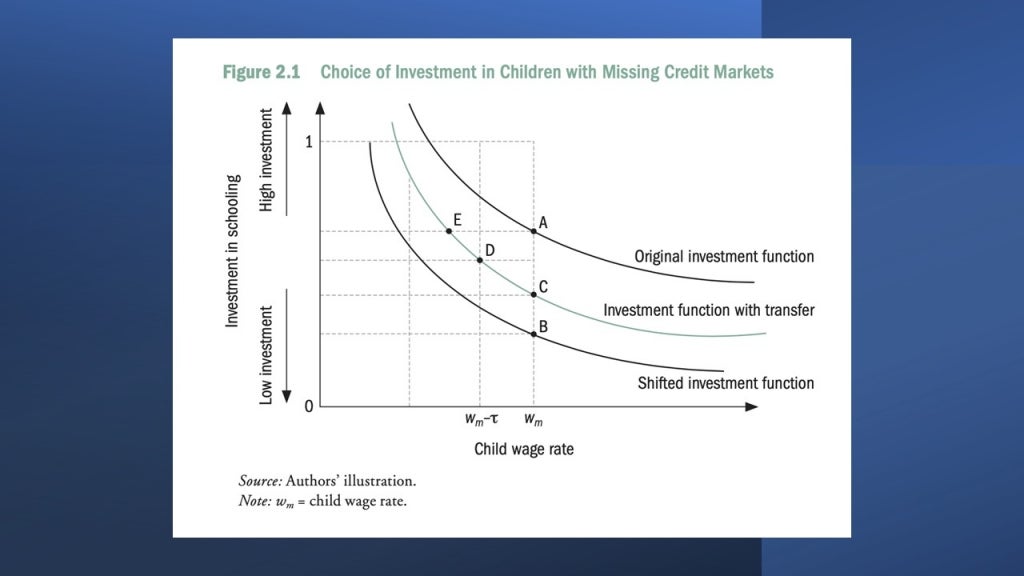

When I teach graduate students about the economic rationales for CCTs, I like to use the following figure – taken from the chapter written by Chico Ferreira in this World Bank policy research report on CCTs. Suppose that parents underestimate the returns to the girls’ education, such that instead of investing in schooling at level A, they invest at level B. With borrowing constraints, a UCT might move this HH up to point C (shifting the demand curve upwards, i.e. the income effect), while adding a condition might move them along the same curve to point D (the price effect).

Getting back to the distortions, we can see in this figure that the government can set the size of the CCT too high, which would cause households to overinvest in education (or whatever behavior is being conditioned upon). This is the area that is the northwest of point E in the figure above, which would cause households to invest in schooling more than they would have under no market failures other than credit constraints: children sitting in empty classrooms, people attending subpar health facilities, etc.

So, there are not only tradeoffs from attaching conditions to cash transfers (see, e.g. Baird et al. 2011, 2013), but there may further be distortions that make the CCT worse than a UCT if the transfer size is not carefully calibrated. The price effect depicted above can essentially turn negative – even in terms of social welfare. There have been recent other papers on the role of conditions in cash transfer programs, just a few of which I list here: Gazeaud and Ricard 2021 on potentially negative effects of CCTs on test scores; Mookherjee and Napel 2020 on the design of CCTs for Pareto improvements over UCTs or UBI; Bergstrom and Dodds 2020 on the targeting benefits of CCTs.

Bryan et al. (2021) design an experiment to identify a distortion in the area of seasonal migration: if such migration is costly and potential migrants who can benefit from it underestimate the income gains, then CCTs can improve over UCTs to induce migration. However, if the transfer size is too high, this can induce a sort of negative selection into migration, among whom the returns to migration might be not only too low but actually negative (the authors have their own diagram, Figure 1, to highlight the theoretical considerations here). So, the authors design an experiment, in which target households are randomly assigned to the following intervention arms (Table 2): (a) UCT (IDR 150,000); (b) CCT-Low (IDR 150,000); CCT-Low+ (IDR 150,000 + an equal amount transferred as a surprised after check-in at the migration destination); and CCT-High (IDR 300,000). The CCT-Low+ arm is there to have the income effects between CCT-Low and -High wash out while the latter still induces more people into migration, i.e. to isolate the distortion from the increased encouragement.

All the main findings are in Table 3. We can see that 42.3% of those in the CCT-Low arm (although it is not clear if this mean is for CCT-Low or CCT-Low/CCT-Low+ combined) checked-in at the destination vs. more than 53% of the CCT-High group. But, despite the fact that take-up is increased by 11 percentage points (pp), the migration season income of the CCT-High group (I am assuming the income excludes the transfer, i.e. just earned income) is significantly lower than CCT-Low+ (p-value=0.015) and marginally so than CCT-Low (p-value=0.10, see Column 6). The income in the CCT-High group is lower by about 20-30K, which is about 17-24% lower than the mean earnings in the two CCT-Low groups: it’s clear that the higher transfers are inducing some people with lower earning potential through migration. The marginal folks who would migrate at IDR300,000 but not at 150,000 are much less likely to earn more by migrating.

The authors argue that when the transfer amount is larger than the amount needed to cover migration costs, then it starts being distortionary. This makes sense and may well be true, but Figure 5 and Table 6 in the Appendix show that the average travel expenditure is about IDR 40,000 (with a maximum of about 100,000), so the CCT-Low amounts are already well above the cost of transport. So, while the experiment has suggestive evidence of inefficient distortion of HH behavior in the CCT-High group, it is possible that even the low amount is too high – without an arm offering, say, IDR 50,000, we won’t really know…

In Columns 7-10, the authors examine the heterogeneity of effects by baseline socioeconomic status (SES). While statistical power is an issue here, there is evidence to suggest that the effects are coming from large CCTs inducing more migration among households with below-median SES (columns 7-8), and incomes being also lower in that subgroup under CCT-High. In fact, the estimates for the CCT-High group seem to me to imply negative returns among low-SES HHs compared to the UCT group: they might have earned more (non-transfer) income if they were given a UCT instead of a large CCT conditional on migrating. It’s important to note that this is clearly NOT true for either CCT-Low arm: the condition to migrate accomplishes what was intended in those arms – even though that is, of course, not evidence of higher welfare but simply higher earnings suggestive of some market failure such as an underestimation of earnings from seasonal migration.

There are a few weaknesses in the working paper. First, as I mentioned above, statistical power is borderline, especially for the heterogeneity analysis that the authors want to conduct. Perhaps related to this, there is some baseline imbalance, which puts the suggestive findings in some doubt. Finally, I find the discussion around Table 3 a little confusing. For example, the mean in the control group for the dependent variable (accepting offer) is 0.928 in columns 7-8, but it’s not clear what share of this group migrated, which seems important for interpreting the results. Also, I think that we want to know whether the interaction effects are significantly different than each other between CCT-Low and CCT-High – not just the main coefficients. Finally, the CCT-Low and Low+ are sometimes combined, for reasons that are not clear (power, I assume). As mentioned above, in columns 1-6, it’s not clear if the means of the dependent variables is for CCT-Low or Low/Low+ combined. Finally, it would be good to know whether the effect of CCT-High (compared to UCT) is really negative or not.

But, these issues do not take away from the fact that this is a really nice idea to add some evidence to the CCT-UCT literature by designing an experiment that isolates the distortion caused by CCTs that are set at a level above the optimal. The issue of setting the transfer level correctly is one that gets less attention than it deserves in real-life policy settings. This is especially the case because, given a fixed budget for transfer programs, transfer size determines program coverage. In this sense, this paper serves an important purpose to show the interplay between conditions and transfer size in economic inclusion programs. It reminds me of two other papers in which this issue came up in our work: in Baird et al. 2013, as Bryan et al. (2021) also mention in their paper, we show that CCTs improve psychological wellbeing among adolescent female beneficiaries in Malawi (compared to both the control group and UCTs) when the transfer amount is small but that doubling the transfers given to parents conditional on the girl attending school is enough to wipe out the beneficial effects (without necessarily improving schooling outcomes). The other is from our evaluation of a cash transfer program for refugees in Turkey, where the issue is not conditionality but coverage: fairly generous transfers given to beneficiaries have caused a substantial movement of members, especially children, from non-beneficiary to beneficiary households. It is possible that smaller transfers provided to a larger share of program applicants could have avoided such movement without a significant tradeoff in poverty and inequality reduction.

Join the Conversation