Bitter experience has taught me to be very skeptical about most financial education interventions. I worked on one (failed) evaluation in Uganda where so few bank clients showed up that they ended up calling up lots of the control group to try to fill spaces; a program for migrants in New Zealand and Australia that increased financial knowledge but led to no changes in remitting; a large-scale financial education program in Mexico City in which we sent out 40,000 letters to invite people to participate and only 42 responded, and in which, after an alternate recruitment approach, we still struggled to get people to show up after paying them $72 to attend; another financial education intervention in Mexico with 100,000 credit card clients in which only 0.8 percent of the treatment group attended training; and a trial of both an information-based and aspirations-based approach in the Philippines, which seemed to backfire by setting financial aspirations too high. The only program I worked on that really seemed to have any success was one that got migrants and their family members in Indonesia at a key “teachable moment” – right before the migrants went off to earn a lot more money than they ever had before. Here training both the migrant and the family member together had large and significant impacts on knowledge, behaviors, and savings. My takeaway has been that unless you get individuals right before they are about to make big financial decisions that they don’t understand, then most financial education programs are not very popular, lead to small changes in knowledge, and even smaller changes in outcomes like savings or borrowing. I’m also sympathetic to the argument that it is not always clear whether more savings (or less borrowing) is a good thing – since it depends on people’s preferences and alternative investment opportunities.

I’m not the only one skeptical about these programs – in recent links I noted David Laibson’s NBER lecture on household finance in which he said “I don’t think there is compelling evidence that financial education is going to move the needle much”.

A new meta-analysis suggests a slightly more positive outlook

Based on these experiences, I read with interest a new financial education meta-analysis paper (earlier ungated WP) by Tim Kaiser, Annamaria Lusardi, Lukas Menkhoff and Carly Urban that is forthcoming in the Journal of Financial Economics. Based on a meta-analysis of 76 RCTs with a total sample size of over 160,000 individuals, their title gives their conclusion “Financial education affects financial knowledge and downstream behaviors”.

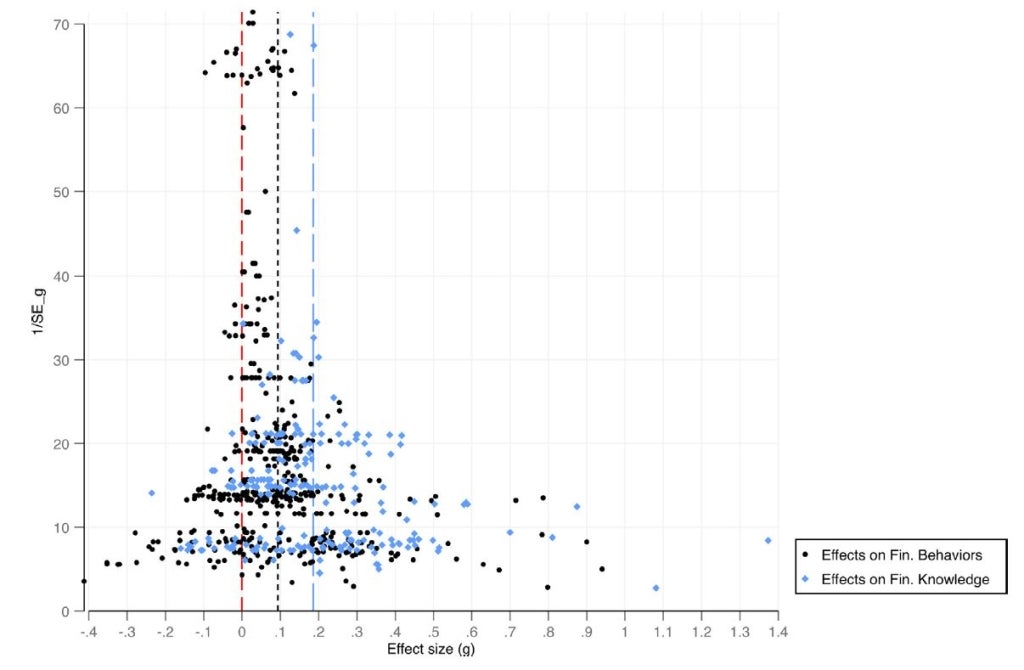

Each study looks at a number of outcomes in terms of both financial knowledge, and financial behaviors (saving, borrowing, remitting etc.), giving them 673 raw effects. The figure below (Figure 2) in their paper plots the precision of these effect sizes (1/standard error) against the effect sizes in standard deviation units. We see the majority of estimates are positive, with an unweighted average effect size of 0.186 S.D. on financial knowledge and 0.094S.D. on financial behaviors. You also see the typical funnel shape, where large effects (in either direction) are only found in studies with low precision.

Figure 2 of Kaiser et al. (forthcoming): Precision of Estimates against Estimate Size in S.D.s

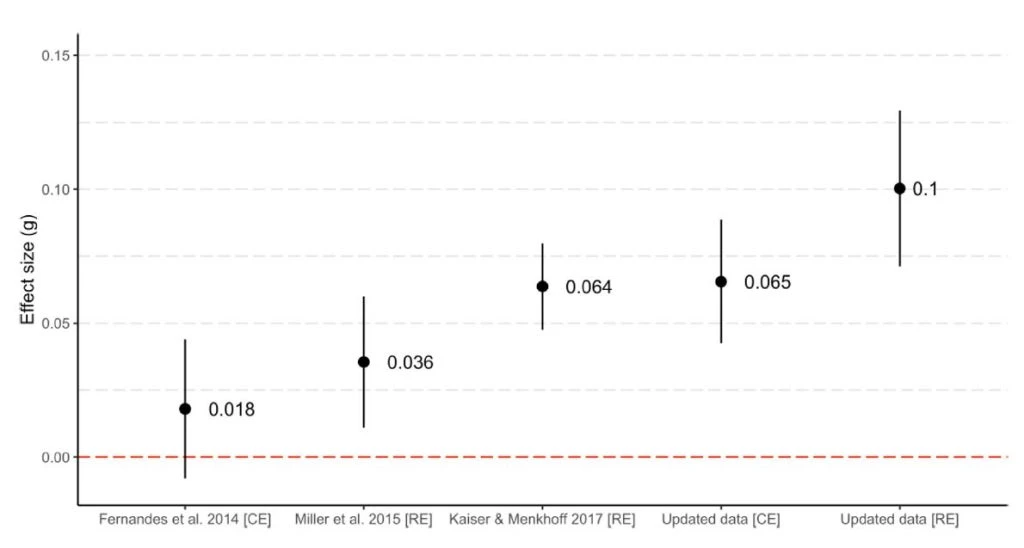

They then do a formal meta-analysis estimation, estimating both a common-effects model which assumes the same effect in all interventions; and the more realistic random effects model which allows for heterogeneity in impacts across studies. This gives an estimated weighted average impact on financial behaviors of 0.10 S.D.s, which is statistically significant. That is, financial education, on average, does impact financial behavior. The second interesting result is seen in their Figure 3, which compares their meta-analysis estimates to those in previous meta-analyses that had used fewer studies – and finds that the impact is now much larger than one would gauge from the earlier studies – including the more recent literature gives a more positive view.

Figure 3 of Kaiser et al. (forthcoming): Impact on financial behaviors compared to earlier meta-analyses

This naturally raises the concern of publication bias. Perhaps the first few times people did financial education RCTs, journals were happy to publish a (close to) null result (as in the classic 2011 study by Cole et al. in Indonesia). But after the first few studies, journals may only be interested in publishing studies that show big effects. Researchers may never even bother writing up studies in which take-up is really low, or impacts not statistically significant, so looking just at working papers won’t solve this problem. A very nice feature of this Kaiser et al. paper is that they take this possibility seriously. They first note they tried looking at the AEA RCT registry to see if there were a bunch of abandoned/non-published RCTs, but only 14/76 studies in their sample are in the registry, so this approach isn’t much help.

They then turn to recent work by Andrews and Kasy in the 2019 AER, who develop a bias-correction method for publication bias. The assumption here is that studies with different standard errors don’t have systematically different estimands, and so one can non-parametrically use the funnel plot in Figure 2 above to infer whether there are “missing” estimates. Using this method, the authors do estimate that statistically insignificant estimates are less likely to be published. Reweighting the analysis to account for this reduces the estimated impact on financial behaviors to 0.057 S.D., and the impact on financial knowledge to 0.15 S.D., both of which are still significantly different from zero. The paper then goes on to look at how these impacts vary with type of outcome (slightly larger for saving than borrowing), intensity of the intervention (suggestive evidence that effects are larger for more intense interventions), type of intervention (suggestive evidence that impacts are smaller for nudges and online education), and characteristics of the population.

How big an effect is this?

Taking these bias-adjusted estimates of 0.15 S.D. on knowledge and 0.057 S.D. on financial behaviors, leads one to ask whether this is an important/useful effect or not. Kaiser et al. attempt to put these magnitudes in perspective by comparing to other types of programs. They note that the impacts on financial knowledge are similar in magnitude to that of the typical education intervention on math or reading test scores, and that those on financial behaviors are perhaps similar to those of behavior change interventions in the health domain. Moreover, given that most interventions are relatively short in duration, and that behavior change is hard to achieve, perhaps the problem is that people often expect too much from these interventions.

But, to my mind, whether 0.057S.D. is a meaningful effect size is still not particularly obvious, because S.D. are a lousy way of comparing outcomes. To be fair to the authors, this is the usual way of comparing effect sizes in meta-analyses – but just because something is typically done this way, it doesn’t mean I have to like it. I understand the need to do this for the knowledge measures, but there are much better metrics that one could use for aggregating and comparing impacts on financial outcomes. For example, one could look at the average impact on the proportion of individuals having bank accounts, or on the percentage increase in savings relative to the control group, or on the dollar value of savings or loans taken. For example, if 20% of individuals use a bank account, then 0.057 S.D. is a 2.2 percentage point increase – which could be worth doing if the financial education is inexpensive, but is pretty small in absolute terms. They note that the mean (median) costs of programs per participant are around US$60 (US$23). As an example in a developing country setting, for the evaluation I recently did in the Philippines, mean savings balance is around US$142, with a standard deviation of around US$164. So a 0.057 S.D. is around a $9 increase in savings. If it is costing even the median of $23 per participant to get them to save $9 more, then this does not seem good value for money.

Meta-analyses do not need to be done with S.D.s as units. For example, in her well-known meta-analysis of microcredit programs, Rachael Meager standardizes all units to USD PPP over a two week period. This allows her to make conclusions like the posterior mean impact on profits is US$7 PPP, compared to a control mean of US$95 PPP, or less than 8 percent. Likewise, my meta-analysis of business training experiments aggregates studies in terms of the percent change in profits and sales, to end up with an effect size of 5 to 10 percent. So it is definitely possible to do meta-analysis comparing outcomes in units of meaningful economic significance. One problem for doing this for financial education interventions (and in many other meta-analyses) can be that different studies measure different outcomes. But I would argue that if the outcomes are different, maybe we should be a lot more cautious about trying to aggregate the studies in the first place.

Putting these general issues that apply to so many meta-analyses aside, this is a carefully done meta-analysis, and I appreciate the efforts the authors have taken to look at issues like publication bias, time horizons, and study heterogeneity. I think it should cause me at least to update my priors slightly. Modest, but positive effects are useful if they can be done cheaply, and so financial institutions rolling out nudges and reminders seem helpful, if not exciting. And small average effects can come with large heterogeneity and large effects for some individuals, so some people may benefit a lot even if the average person does not. Moreover, there is an active body of research on adult training pedagogy and on behavior change that we might hope could lead to more effective interventions in the future. Nevertheless, I’m still going to be very cautious about getting involved in another financial education evaluation, unless it really seems centered around a timely and large financial decision, where individuals can act immediately on the knowledge learned in a way I think could make a major difference in their lives – basically help people refinance mortgages rather than cut back on avocado toasts and coffees…

Join the Conversation